Crazywise: A Filmmaker Explores the Heart of Mental Illness

Phil Borges is a dentist-turned-photographer, author, filmmaker and social change storyteller. For more than 25 years, he has been documenting indigenous and tribal cultures in some of the world's most remote, inaccessible areas. Phil uses his gifts so that the rest of the world might understand the challenges individuals living in remote area face, and the resilience, spirit and wisdom they possess. What follows is the official trailer of Phil's most recent film, and an edited version of an Awakin Calls interview with him. You can access the recording and full transcript here.

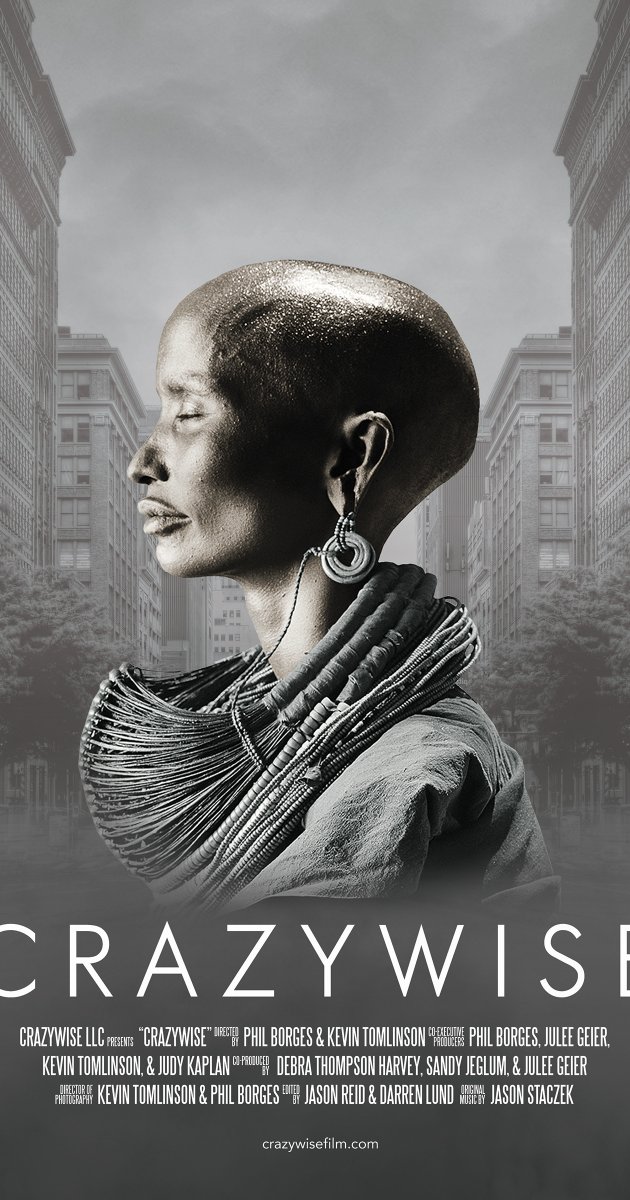

Pavi Mehta (moderator): Phil Borges’ breathtaking work has been featured in National Geographic and the Discovery channel, as well as museums and galleries worldwide. His award-winning books on human rights issues include "Tibetan Portrait, Enduring Spirit," "Women Empowered," and "Tibet, Culture on the Edge." His program "Stirring the Fire," highlights extraordinary women worldwide who are breaking the gender barrier and uplifting their communities. Borges’ online program, “Building Bridges” enhances cross-cultural understanding and global citizenship among youth worldwide. Phil's current project, which he has been working on the last four years, is “Crazywise,” a documentary exploring the relevance of shamanic practices and beliefs and how they could benefit modern mental health systems. We're deeply delighted to have you, Phil.

Phil Borges: Well thank you, Pavi, for such a wonderful introduction.

Pavi: I want to go back to your roots. It was very clear from your work and the kind of access you've been granted, that you have this global worldview and sensitivity and an immediate empathic connection with people who've been misunderstood, marginalized or simply not seen. I'm curious to know what forces or events in your childhood or young adulthood helped shape your sensitivity to others.

Phil: Well, one of my strongest childhood memories is right after my father died. I was 7 years old. Around the same time, my Aunt Maude lost her husband and her only son within weeks of one another. These events caused her to suffer a mental breakdown and she was institutionalized. When she was released, she came to live with us. Because of my father’s death, I was in this very vulnerable state, unsure of what was happening. And my mother was falling apart from the trauma of losing her husband. In any case, Aunt Maude began talking to spirits. At night, she would call them into her room and bang on the walls. I could hear her chanting. It was all very strange to me. On a couple of occasions, she asked me if I wanted to see my Dad. I was unsure of what death was, and I felt this overwhelming curiosity--and fear. In retrospect, that was one of the big events that formed my path.

In the mid-1950s, when I was 10 or 11, we were living in a lower middle-class neighborhood in San Francisco. Most of my friends were juvenile delinquents. So my mother, in her wisdom, sent me to live with relatives on a ranch in Utah. They were subsistence farmers. They grew all their own food. I absolutely fell in love with that lifestyle. I wanted to be a farmer.

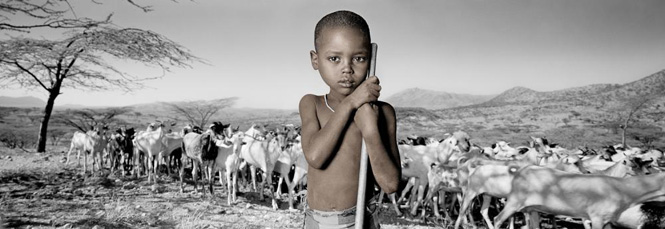

Kinesi, 6, Kenya – (c) Phil Borges

So I've always been attracted to people that live close to the land. I think that's one of the things that really set me off on this journey-- going to remote areas where people are hunter-gatherers or grow all their own food. I love very small communities where there's a lot of connection not only to the land but to their ancestors. They will set aside some food for the ancestor’s spirits, pray to the ancestor spirits. They put spirit energy into the forest, the sky, the mountains, the animals.

Pavi: Did you have any key relationships in your childhood that helped you become strong and resilient despite living in a rough neighborhood?

Phil: When I was younger, I wanted respect and I'd get it any way I could. The kids at my elementary school got more status and respect for going to juvenile hall than for getting good grades. That's the way it was there. If you're asking who helped me get out of that milieu, it was my mom. Although we were poor, she moved us from San Lorenzo to Orinda, an upper middle class neighborhood. It got me into a whole different set of people and social values, which was huge. But it was also a hard transition. All of a sudden I was thrown in with all these kids getting good grades to prepare for college. I didn't know how to do that. Freshman year in high school, I was falling behind. And I was trying to be a tough guy, which didn't work in terms of getting status and respect in Arenda. I remember a time that my friends from my old neighborhood called me up and said, "Phil we're going to come out to see you." I said, "Thank heavens! The kids here are weird. They study all night." But when they showed up, they were all dressed in black and had chains in the back of the car. They had been in gang fights. After they left, I thought, "Whoa, I don't want to be there and I don’t belong in this new place. I was in limbo."

But then something amazing happened. I was getting C's and D's in algebra. One day, I was walking down the hall and my algebra teacher stepped in front of me and said, "Phil, I see you coming to class and I see that you just spend 5 minutes doing your homework, yet you manage to answer a lot of the questions in class. Do you know most of these students are spending an hour or two at home doing their homework? You would be amazed what would happen if you spent a little more time on this. You've got a gift." Then he walked away. I was stunned. Then I started performing for him and I learned how to get A's in other classes. So just that one little encounter turned me around.

Pavi: That's such a special story. I understand you grew up within the Mormon tradition, went to church nine times a week and, as a 12 year old, you became a priest and had to give a 2-1/2-minute sermon. Can you share a little bit about the topic you chose and how it shaped your later human rights work?

Phil: My mother became very religious after my dad died. It was a good experience because the Mormons take care of their own. We were poor and they always gave me work. But as I got older, I started questioning the dogma, especially that all males had to become priests at age 12. You go through an ordination. It also really bothered me that women or people of color could not hold the priesthood. There was one Hawaiian person who had that disease where the pigment starts dissolving and part of your skin turns white. In a testimony meeting, he actually said that he thought his skin was turning white because he was becoming righteous. I did a 2-1/2 minute sermon on that issue and how when I would ask the elders about that dogma, where it came from, and why, the answers I got made no sense. That was the beginning of my break away from the church. I became an atheist and transferred from Brigham Young University to Berkeley at the end of my freshman year, where I studied physiology.

Pavi: Then you became a dentist and practiced for 18 years. You quit and became a photographer. How did you end up doing the work you are now doing?

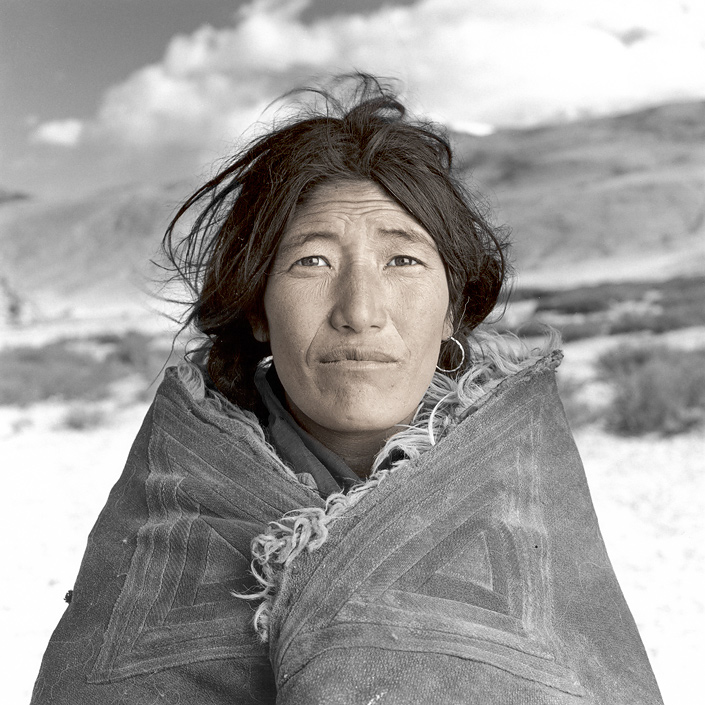

Phil: I wanted to have access to a darkroom because I had taken black-and-white photos of my son's birth and needed to develop them somewhere. I asked if I could use the darkroom at this community college and was told I had to take a photography class to use it. I had this inspirational teacher, Ron Zack, and fell in love with photography. I had been restless in my dental practice; it wasn't fulfilling me. So when I found photography again, I decided I have to make this change. I knew it was going to be uncomfortable. I did not want to be poor again. I thought the only thing I needed to do was learn how to make money with this new medium. So I tried commercial photography. It took me several years before I got a job, so I did my own work while waiting to get clients. Because I was doing work close to my heart, it really propelled my advance in photography. Then, I began getting commercial work and became pretty successful at it. I shot covers for 50 romance novels. Eventually, I asked myself, “Is this really what I dropped out of dentistry for?” That's when I decided to do a project in Tibet on the Tibetan people. That project put my images in galleries across the country and in Europe. I didn't have to do commercial work anymore. And I started doing work centering on human rights issues that people, especially in the developing world, face.

Pavi: One of our mutual friends, Rajesh Krishnan, sent me a quote from a Tibetan representative here in the U.S. who said, "At a time when so much is being said and written with little impact, Phil's images, speak for themselves and gain the understanding Tibet and the Tibetans need." I thought that was a powerful testimony because at that point you hadn't been anywhere in the east before.

Phil: Yes, that was my first trip.

Pavi: The Tibetans have a very distinct history and then a very unusual-- I think by western standards--way of processing and holding and carrying what has happened to them and what continues to be their difficult legacy. I'm wondering how that struck you and how you interfaced with it?

Phil: It was quite profound, actually. When I went over there the only

.jpg) thing I knew was that I wanted to do this human rights story. I had learned about how their country had been invaded in 1959 and how the Dalai Lama had to escape and go into exile. But then I started interviewing these people who had come over the Himalayas and escaped from China and Tibet into India where the Dalai Lama lives. I interviewed individuals who had been in prison, like this monk, who had just gotten out of prison after 33 years. While there, he was beaten, starved, and most of his fellow monks died. He was kind and gentle. He was only 62 but at the time he seemed older to me. Then I went to hear the Dalai Lama talk in Dharamsala. He told the audience that they should treat their enemies as if they were precious jewels because the enemies are the ones who are going to help them deepen their patience and tolerance. I thought, “Whoa, this is a very, very different culture. The leader is not using fear and hatred to gain power like you see happening in our world today.” Just a very different and refreshing way of looking at things that really made an impact on me and informed the way in which I framed the work I did for the Tibetan people.

thing I knew was that I wanted to do this human rights story. I had learned about how their country had been invaded in 1959 and how the Dalai Lama had to escape and go into exile. But then I started interviewing these people who had come over the Himalayas and escaped from China and Tibet into India where the Dalai Lama lives. I interviewed individuals who had been in prison, like this monk, who had just gotten out of prison after 33 years. While there, he was beaten, starved, and most of his fellow monks died. He was kind and gentle. He was only 62 but at the time he seemed older to me. Then I went to hear the Dalai Lama talk in Dharamsala. He told the audience that they should treat their enemies as if they were precious jewels because the enemies are the ones who are going to help them deepen their patience and tolerance. I thought, “Whoa, this is a very, very different culture. The leader is not using fear and hatred to gain power like you see happening in our world today.” Just a very different and refreshing way of looking at things that really made an impact on me and informed the way in which I framed the work I did for the Tibetan people.Pavi: That's powerful. You've seen, I'm sure, incredible beauty as well as incredible suffering. How do you not tip into anger or despair?

Phil: Well I do tip into anger. I have things come up all the time that bother me. But I can say that I am more detached from it now. I look at it; I see what it is that I'm reacting to and that my reaction isn't helping matters at all. Having inspirational people, like the Dalai Lama, or the people I meet in my everyday life that are doing things in a way that I think it should be done helps me. Then, I can regroup and regain my composure and proceed in a more compassionate or effective way.

Pavi: It's a work in progress for all of us. When I look at your photographs, one thing that leaps out is how intimate they are. They're staggeringly beautiful. They have an unearthly quality, yet are so much of the earth. I understand that your camera is just inches away from your subjects, yet they are so unguarded whether they're children or older women and men. Can you speak a little bit about that?

Phil: Well I have a much easier job photographing people who are remote and not used to cameras. They are a lot les self-conscious. They're not worried whether they look too old or fat or if their nose is too big. I usually go into a place and start with the kids. Kids are a lot more open than adults, almost always. Then the adults warm up to the process. Once they're in that space, they're not in self-conscious mode. They're open and wondering about the whole process.

Phil: Well I have a much easier job photographing people who are remote and not used to cameras. They are a lot les self-conscious. They're not worried whether they look too old or fat or if their nose is too big. I usually go into a place and start with the kids. Kids are a lot more open than adults, almost always. Then the adults warm up to the process. Once they're in that space, they're not in self-conscious mode. They're open and wondering about the whole process.

Pavi: I think you're being very humble in what you've been able to do. But it is an interesting point you bring up. I was thinking about your childhood--the break from the church, your atheism, adopting the scientific lens and then being drawn into these cultures where reverence and spirit is so much a part of every moment almost, rather than being compartmentalized. How have you processed that and how has that affected your work? For example, you've met remarkable shamans and healers who are in touch with something that stumps the most rational, scientific minds. How have you worked with that? How has that changed your own understanding?

Phil: Well again, that's a work in progress. But I must say I am much more open to the mystery of life and comfortable with it being as a mystery. I could give you anecdotes of things that have happened with the shaman and their ability to predict. I have no way of explaining it, but it really caught my attention. Also on a rational level, I see how their beliefs, their metaphors, serve the human condition so much more than our reductionist, scientific views do.

Pavi: Do you have an example of that? Of how their metaphors---

Phil: One of the things that I witnessed, which is in our movie, Crazywise, was a shaman in the Amazon jungle, named Mangatui, go into a trance and shape shift. He became the energy or spirit of the jaguar. At that time, I was hosting a program for the Discovery channel. I was filming him in his hammock as he growled and underwent a trance-like state and took on energy. At the time of filming, I wondered, ‘What is going on here? Is this a performance?’ But as I've grown, I’ve come to believe that he was becoming part of the environment, separate from his bodily self, the thing we think we are. For me, spirituality means building connections to everyone and everything around you. Mangatui was building those connections for his tribe as they all gathered around him as he did this shape shifting.

When I look at some of our religions, and I don't want to come down on the Mormon church, one of the things, there was a lot of good about it and there were issues. One of the issues was that this was the only true church. Over and over again I heard that. We have the fullness of the truth. Some religions only have partial truth. That's a separating narrative. Whenever you hear that stuff, wait a minute, hold on, that's ego speaking. So I look for the metaphors and beliefs that connect --- that’s what I'm drawn to. And I see a lot of that in the indigenous world. And I also want to say that I don't want to over romanticize these people because they're human beings and they're going through a similar process as we in the modern world. We're all struggling with our egos and our sense of separation, our sense of self-righteousness. It's no different for them, but they do have guidelines that are helpful that we can learn from them.

Pavi: That's a beautiful way to frame it and that definition you gave  us for spirituality-- I'm going to hold on to that. I've never heard it framed that way before, but it hits a deep chord. People who are interested in learning more about your meetings with shamans in Kenya and remote areas of Pakistan and India, can watch online. Right now, I am going to segue into one of your TED talks from a couple years ago that deals with the themes of Crazywise. The film hasn't come out yet, but your TED talk has already generated almost half a million views. Did that surge of interest in your film surprise you? Why is this a crucial and timely issue that we need to be talking more about?

us for spirituality-- I'm going to hold on to that. I've never heard it framed that way before, but it hits a deep chord. People who are interested in learning more about your meetings with shamans in Kenya and remote areas of Pakistan and India, can watch online. Right now, I am going to segue into one of your TED talks from a couple years ago that deals with the themes of Crazywise. The film hasn't come out yet, but your TED talk has already generated almost half a million views. Did that surge of interest in your film surprise you? Why is this a crucial and timely issue that we need to be talking more about?

Phil: I've done three TED talks on the subject of shamanism, and each time discussed mental health more. I must say I've been so nervous in all those talks because there's so much controversy surrounding the term “mental illness.” It’s such a minefield that will alienate a lot of people. So it's always a challenge to do it just right in 18 minutes.

But so why is it so important right now? Why is it coming up? Well, I'm kind of this every man because I have no background in mental health other than the aunt I spoke about. This subject kind of came to me and chose me. And as I've been involved in it over the last four years, I'm shocked to see the crisis we're in, in terms of mental health. The rate of people being imprisoned who have a mental illness is incredible. Fifty-six percent of our prison population has a mental illness. Rates of depression are rising and 50 percent to 30 percent of the homeless population has a mental illness. Each day, 1,100 people go on disability insurance related to mental illness, and for young people over a lifetime those payments would add up to $3 million each. If you do the math, you realize that it's unsustainable. We have a narrative driving the treatment and research that is just not working. In fact I've come to believe it's harmful. I think the reason so many people are interested is because we are definitely in a crisis.

Pavi: Kind of sets the tone for diving in deeper. Maybe you could talk a little bit about how Crazywise started and what you see as the core messages of the film. What would you like to see people take away?

Phil: It started with my work with the indigenous world when I began to meet individuals who entered trance-like states to serve as healers or clairvoyants--they call them seers or predictors--of their community. I started interviewing these people and found that most were selected in their youth by having a crisis of some sort. Once in a while it was a physical crisis or sickness, but typically it was a mental, emotional crisis. Many talked of seeing visions, having intense dreams, hearing voices, feeling very frightened. Some felt like they were dying. Typically the ones I talked to who became healers and seers were taken aside by an elder, usually a shaman, and told that their condition was a sign they had special sensitivities that could be very valuable to their community. They could not ignore what was happening to them. They could look at it as a calling, and they had to answer this calling. And if they didn't answer it, they would continue to be sick and could eventually die from it. So they would enter an initiation period where they would be guided and mentored by this elder who, at one time, had gone through the same thing. This was handed down. That way of framing mental illness was really interesting because it our culture we believe that such an experience is a disease of the brain. And the biomedical narrative we now hold is that we don't have a cure for it. We have these medications that can stabilize the person mainly by tranquilizing them. But there's no cure and it's sort of a lifelong sentence. So during the process of doing Crazywise, I’ve met a lot of people who label themselves as people with lived experiences, people who have lived through one of these crises and are now leading very functional lives. When asked what helped them and what didn't, they'll say number one is the way my condition was framed or when I finally realized that this was an experience I could learn from. When I had somebody that was supporting me while I was going through this dark night of the soul, which made all the difference. When the experience is framed properly, you don't get this self-fulfilling narrative that condemns the person to a lifetime of illness. They were helped to find the meaning of what they were going through. They were able to find out what their symptoms were telling them rather than just suppressing the symptoms. Then, they were given them a purpose for their life. You can be a very valuable person for this community. And if you start talking to the people who go through these experiences, they are very, very creative, exceptionally bright individuals. They think outside the box. Many of them, including the main character in our film, have what looks like a spiritual experience. The definition I used earlier where Adam said the first time I felt at one with the universe, where I was it, it was me; Many sages refer to this as an "aha" moment. Many of these people going through these breaks have that experience and then, if they're not supported correctly, told it's an illness. You can imagine you're 20 years old, you're vulnerable, maybe you're away at school, maybe you've had a love relationship go bad, things aren't going well, you're away from home for the first time and your brain goes off into another reality to protect your psyche. Then you're told by an expert wearing a white coat that your brain is broken and diseased and your whole identity changes. Just like the teacher who came up to me in the hallway, he changed my identity around my belief in myself as being a good student.

Deven: If the person having the break is not open to guidance, then guidance from community is impossible. Could trained guides help? I would be open to learning other approaches and views from indigenous cultures.

Phil: From indigenous communities I have learned the importance  of connection and community, not only the community of people but of the environment and the world of our ancestors. Being connected to that whole flow of life is a healthy state for the human psyche. Our current biomedical treatment narrative or paradigm unfortunately labels the individual in a very stigmatizing way as the "other." There are the mentally ill over there and there's us normals over here. One in five people will have a mental illness, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. It's a very normal reaction to circumstance. It’s the "othering" that we have to learn to avoid.

of connection and community, not only the community of people but of the environment and the world of our ancestors. Being connected to that whole flow of life is a healthy state for the human psyche. Our current biomedical treatment narrative or paradigm unfortunately labels the individual in a very stigmatizing way as the "other." There are the mentally ill over there and there's us normals over here. One in five people will have a mental illness, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. It's a very normal reaction to circumstance. It’s the "othering" that we have to learn to avoid.

I think the most important thing is to listen with an ear to understand, not to judge. The person in this state – their psyche has chosen to protect itself by going into another reality. So the person, if they’ve been put into a deep fear--could be claiming to be Jesus, or to be from Mars, or that the CIA is after them. One of the most important things is to listen to them and try to understand what these voices, or what these beliefs, are indicating. And, of course, if the person has been frightened enough, typically what happens, especially with young people away at school, they are taken in a cop car or an ambulance to an emergency room, strapped down in the back room until the psychiatrist can get there to inject them with a mind-altering drug. If you can get to the person before they're put into another state of fear, that's ideal. But if you can't and they are just really acting out, maybe they haven't slept in a week, then, of course, some of these medications can get them to a place where they can start to be supported in other ways, which is very valuable. So medications do have a place. What’s troubling is the belief that they have to be on these medications for the rest of their life, as well as the over prescription of these medications. We are now pathologizing the normal human experience. If you look at the list of disorders in the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders written by the American Psychiatric Association, the list of disorders has grown by 300 percent since it was first published in 1952. So you're getting a medication for something like sibling rivalry disorder, or for disruptive mood disorder. All these young kids are being put on medications to handle what used to be "boys will be boys" or normal grieving. If you lose your spouse after 40 years of marriage and go into grief that lasts longer than a couple weeks, you can be diagnosed with severe depression disorder.

Deven: You touched on patience, listening, taking time to understand; and all these things are so powerful. We have a beautiful reflection from Rumi: When I run after what I think I want, my days are full of stress and anxiety. If I sit in my own place of patience, what I need flows to me and without any pain.

There's one more question Phil, from Karen, and the question is "How does someone who is struggling with a mental condition come to a place of saying it's a gift actually?"

Phil: Well to come to a place where you look at it as a gift ties it a little back to what you just read from Rumi. The stress and depression are symptoms. What's underneath those symptoms? It isn't always easy to find that answer, but it's worth looking for. The problem with looking at it as a disease of the brain is you are turning over all the responsibility to medical experts and scientists. Mental health is a responsibility not only of the individual, but the community. And we have given away that responsibility. I say if you're struggling, and we all struggle with one form of it or another, you have to say, “What is this struggle about? Why I am struggling with this? What does this tell me? Why does this problem push my buttons?” It isn't always easy, but the fact that we're being led to believe that we're going to find a magic bullet that we're going to one day be able to turn off a certain gene sequence, or take a certain pill without any side effects and then our lives will be perfect. That's going down a rabbit hole that’s not going to bear fruit in my opinion.

Deven: From Kate (who sent a question through the web form) “I've had extreme social anxiety since I was a child but was always told I was just too sensitive, took things too seriously, was weak, wasn't strong enough, etc. I wasn't properly diagnosed until 50 with moderate PTSD due to events in childhood and adolescence. Appropriate medication and lots of wonderful therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy, plus unending support from loving husband, has given me a wonderful life. I’m so grateful for all of this help. I know even though it took a long time to get better, at 67 I am still a work in progress. I know that I will be okay. My faith has helped me a great deal.”

Phil: Spiritual beliefs are so important. Well who isn't a work in progress? The fact that she has a loving husband… I wonder if she has realized what a special gift her extra sensitivity is, even with the pain that it brings her. Being sensitive is having more information come in than the average individual, on a certain level. And I wonder if she's found enough support-- that she hasn't gone into this deep despair and disability. That is what this sensitivity can lead to if it isn't supported in the right way. One therapist said to me, and he'd been in the business 40 years, “My practice took a whole different shift when I stopped looking for the diagnosis, the label, the problem and started looking for the person's strengths.” What were the strengths of this individual that made them unique? Look for your strengths.

Mish: Many years ago, I was going through a life crisis. I was in a great state of fear and anxiety. I was in such a state that I didn't think I'd be able to turn to my friends or to doctors. Instead I went out and I sat in my back yard, it was a sunny day, and I looked up at the sky and said, "I need help, I can't do this by myself." And this sounds really strange, but right away at that moment from the tips of my toes to the top of my head an energy filled my body, a rush like every chakra was opened. From that moment on, the fear and anxiety was replaced with peace and I felt great love towards everyone involved in this frightening situation. So I know it was happening at the universal life force energy. Is there any other explanation that you might have for what happened?

Phil: It sounds wonderful. I think you've explained it very well. A couple things come to mind -- you surrendered, you didn't try to fight the symptoms. You connected yourself to nature in a very spiritual way in the backyard, looking up at the sky and you had faith that you could be answered. I think that probably helped a lot, don't you?

Mish: Yeah, I just felt we can turn to the universe and ask for help and I don't know if some people believe it's angels coming to their aide or ancestors. I only know that we can ask for help out there and it can come. And sometimes it can come immediately. That was before my association with Kindspring and that's what brought me into loving everyone. Sometimes you do need medication and help from doctors, but sometimes you can ask for help out there.

Phil: And you believed you could get it.

Mish: Well I didn't really know if I was going to get it, to be honest, Phil, I just knew I needed help and I was scared as hell and so I went out and asked and was grateful for what happened. I would encourage anyone who's going through something that's frightening, go out into nature and ask for help.

Phil: Yes, we have heard that from many of the people we've interviewed--going out in the back yard and gardening; getting your hands in the soil. When we were in Brazil, we looked at how mediums worked in the psychiatric hospital. Even though Brazil is a first-world country they have 13,000 spiritual centers where people believe the energy can be transferred much like it was to you. And these people that have the sensitivity are volunteering. And the 50 hospitals that have these volunteers are the most popular psychiatric hospitals in Brazil. The volunteers do things like pray for the patients, they do passes with their hands transferring loving energy to them; all that stuff that doesn't lend itself to the scientific method. This is the place most patients, most individuals, having heavy mental emotional crisis want to go.

Mish: I hope we get more of that here in the States.

Deven: The question is, ethically if a person has experienced a form of this, is it appropriate to claim disability insurance?

Phil: The main character in our film is right now deciding whether he  wants to apply for Social Security Disability Insurance. All the time knowing that's a label he'll carry the rest of his life. How disempowering will that label be for him? So he's struggling with that. He wants to believe that he can be functional again, start to contribute and lead a fulfilling life. But we live in a very material world where we need resources to survive so that is the problem; that is the dilemma. You're taking on an identity when you go and seek the disability insurance. Not to say that isn't necessary in certain cases, but that is the down side of it.

wants to apply for Social Security Disability Insurance. All the time knowing that's a label he'll carry the rest of his life. How disempowering will that label be for him? So he's struggling with that. He wants to believe that he can be functional again, start to contribute and lead a fulfilling life. But we live in a very material world where we need resources to survive so that is the problem; that is the dilemma. You're taking on an identity when you go and seek the disability insurance. Not to say that isn't necessary in certain cases, but that is the down side of it.

Deven: One of my biggest takeaways is that quote "spirituality to me is building connections to everything and everyone around me." That is so beautifully put especially when I think of all the individualism being promoted so strongly in our society. We are so enamored in celebrating personal success and drive and milestones that we sometimes lose that collective power we all have around us, so thank you for doing that. Phil we always like to ask all our guests, "How can all of us at ServiceSpace help you in your beautiful and touching endeavors?"

Phil: We've been blogging and showing excerpts from the film the last two or three years at Crazywisefilm.com. You can help get the word out about the film and our message, if it has resonated. We're working on it feverishly now to finish it and make sure our message is clear.

***

This interview was transcribed by Dorsay Fisher, and edited by Donna Jackel. Photo credits: Phil Borges. The full-length version of this interview is available at Awakin.org. Awakin Calls are weekly conference calls that anyone from around the world can dial into at no charge. Each call features a unique theme and an inspiring guest speaker.

SHARE YOUR REFLECTION

4 Past Reflections

On Apr 28, 2017 Kristin Pedemonti wrote:

thank you. as someone with different brain chemistry who does her best to view the gifts within, number one being compassion for others, I highly resonated with both the trailer and the interview. I look forward to watching the TED Talks and also seeing the full documentary. Hugs from my heart to yours!

1 reply: Somik | Post Your Reply

On Apr 25, 2017 bmiller wrote:

Wow, I remember when this guy spoke at a Wednesdays several years ago! Interested to see what he's done since!

On Apr 25, 2017 ivorybow wrote:

Those who resonate with the content of this documentary about the failures of western mental health care may be very interested in the work done by investigative journalist Jon Rappoport on this same subject. Also, Dr. Patch Adams has much to say about this issue too.

On Jul 4, 2017 Mat Nyabinghi Dyde wrote:

Very Good! Thank you. I am a non-local traveller...its recently bust so wide open its heavy. Its all poppin open everywhere aint it?. I must go to Bhutan to sit weit the 8 year old boy Rinpoche. The Dzogchen. Thank you

Post Your Reply