From the Rink to the Research Lab: How a Former Olympian is Transforming the Mental Health Landscape

It’s not every day you find yourself chatting with a former Olympian, let alone one whose discipline and determination on the ice has translated effortlessly into shifting the mental health landscape as we know it. Last month, I was privileged to speak with Rachael Flatt, a former competitive figure skater who took seventh place at the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver. Down-to-earth and deeply insightful, it’s no surprise that the 26-year-old, aptly known as “Reliable Rachael”, has already made quite a name for herself.

At the time of our call, Rachael had just completed the first year of her Ph.D. program in Clinical Psychology at the University of North Carolina and was moving into a new house with her fiancée the following day. If that sounds like a whirlwind weekend to you, it’s nothing out of the ordinary for the athlete turned researcher.

The former figure skater is all too familiar with juggling the demands of academics, work, and personal life. Having begun skating at the age of four, she learned early on how to maintain a rigorous schedule, regularly shuffling between skating rinks where she spent eight hours a day and school classrooms where she maintained a 4.0 GPA. Unlike many professional athletes, Rachael didn’t place her education on hold, a decision she credits to personal values she derived from her parents. “My parents really raised me with the mindset that in the phrase ‘student-athlete’, student comes first for a reason because academics and education are of so much importance,” she explained. “I really felt strongly about maximizing my efforts and my time in my academics and making sure that I was really setting myself up well for whatever comes next. As much as I love skating, I knew that I didn’t want to pursue that for the rest of my life.”

Rachael was a senior in high school when she competed in the Olympics, an experience she recalled as surreal. “It was extremely exciting, but also very bizarre,” she said. Many of her classmates did not realize the elite level at which she was competing as she shied away from being cast in the spotlight, often keeping her head down to focus on her schoolwork. Following her Olympic season, Rachael went on to win the silver medal at the 2011 U.S. Championships and qualified for the World Championships. However, a week before the event, she was diagnosed with a stress fracture in her right tibia and ended up finishing 12th. Following that season, Rachael relocated from Colorado to the Bay Area where she attended Stanford University to pursue her bachelor’s degree in Biology with a minor in Psychology.

It was there she began to develop a passion for research, immersing herself in her studies as she struggled to fill the void her longtime skating career had filled. “Leaving the sport was very, very difficult,” she said. “It really felt like I lost a part of myself, a huge part of myself. It was more than just a job, it was more than any one sense of accomplishment. It was truly kind of woven into the fibers of my being and it took a long time for me to really process that, almost two years I think before it really came together that I was no longer going to be skating.”

Rachael retired from competitive skating in 2014 during her junior year of college, ending her career on her own terms after a series of injuries continued to plague her during her 2012 and 2013 seasons. "I left skating when I was emotionally ready and injury-free for the first time in almost eight years,” she explained. “Even though it wasn't anywhere near my best, it was the right time for me. That made the transition to focus solely on my last year at school more manageable, and I am still proud of the decision I made."

Throughout her career, Rachael was far from immune to public scrutiny about her weight and physical appearance, adding to the self-esteem and body image concerns any adolescent might face. “As I grew up from 12 to 17 to 21 during those Olympic cycles, my body was changing, and I got a lot of criticism particularly when I was in my young teenage years for no longer having the same physique,” she recalled. “That’s just part of physical maturity, and so that was something that really took a toll on my body image and my self-esteem over the years, and certainly impacted the career trajectory that I’m on now.”

Body image concerns often develop at a young age and endure throughout one’s life. By age six, girls especially begin to express concern about their weight or body shape, with 40-60 percent of elementary school girls being worried about their weight or about becoming too fat. Moreover, over 50 percent of teenage girls and nearly one-third of teenage boys employ unhealthy weight control behaviors such as skipping meals, fasting, smoking cigarettes, vomiting, and taking laxatives.

Rachael witnessed several of her peers suffer from eating disorders and poor body image due to the “aesthetic nature” of sports like figure skating. "Unfortunately, being in the spotlight, and when you're getting judged based on how you look in an arena full of 18,000 people and nine judges, it's really challenging to not come away with any of those perceptions about yourself."

For young women and men who may be struggling with body image concerns, Rachael suggested expressing their concerns to someone, whether it be a friend, peer, teacher, guidance counselor, physician, or family member. She also recommended seeking information from resources such as the National Eating Disorders Association, Mental Health America, or the University of North Carolina’s Center of Excellence for Eating Disorders.

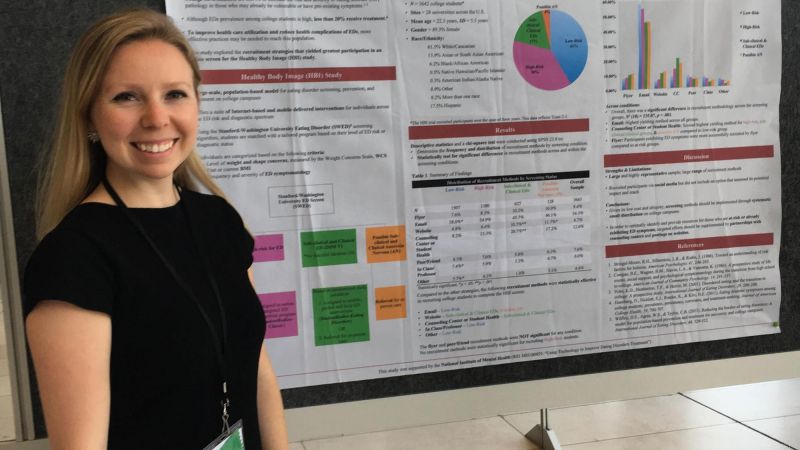

In her graduate studies at the University of North Carolina, Rachael is currently focused on developing technology-based tools for eating disorders and athlete mental health, ranging from brief online assessments to high-end prevention- and treatment-based mobile applications. She wants to see progress continue in making mental healthcare more affordable and accessible. “Having lived in the Bay area for a number of years, I had a number of my friends really struggle to find a mental health provider who was available because [of] their waiting lists that are very long,” she explained. “There are a lot of hurdles that need to be addressed, but I’m very excited to see that a number of organizations are really trying to prioritize this and make some positive changes.”

According to the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders, at least 30 million people in the United States suffer from an eating disorder. Out of American women, 1.5 percent suffer from bulimia nervosa in their lifetime, while 2.8 percent of adults suffer from binge eating disorder. Treatment for eating disorders is particularly difficult, with anorexia nervosa, characterized by an abnormally low body weight, intense fear of gaining weight, and a distorted perception of weight or shape, having the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric disorder, including major depression. “It’s really important that we get a better handle on what these folks need and [catch] these folks when they’re at risk before it develops into a full-fledged eating disorder,” Rachael said. “It’s incredibly grueling work, but it’s also so exciting to see that we’re making progress.”

Rachael is hopeful that the mental health culture within the field of professional sports is changing as awareness continues to grow. “Stigma’s one of the biggest hurdles in mental health prevention [and] treatment, and it’s even worse I think to some extent in some athletic cultures,” she argued. “You’re supposed to portray this image of perfection and no weakness, so it was really challenging to open up and say, ‘I am really struggling’ when that was something that was not acceptable to some extent. I think that is changing now, especially with a number of athletes stepping forward and talking about their experiences with mental health or mental illness.”

Psychology Today distinguishes between two types of mental health stigma, social stigma, which is characterized by “prejudicial attitudes and discriminating behaviour directed towards individuals with mental health problems as a result of the psychiatric label they have been given” and perceived stigma or self-stigma, “the internalizing by the mental health sufferer of their perceptions of discrimination”, which can significantly affect feelings of shame and lead to poorer treatment outcomes. Research suggests that stigmatizing attitudes toward people with mental health problems are widespread and commonly held, regardless of whether one knows someone with a mental health problem, has a family member with a mental health problem, or has a good understanding and experience of mental health problems. The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) offers several strategies to help fight mental health stigma including being conscious of language used to describe mental health conditions, showing compassion for those with mental health concerns, and increasing awareness through educating oneself and others.

Rachael also plans to conduct research around transitioning athletes out of competition and into everyday civilian life, a process she found particularly challenging. On her retirement from skating she said, “That was really something I had done for my entire life at that point. It was something I grew up with and it was something that was just so core to who I was, and without it I just felt this huge sense of loss and this gap that I just didn’t know what to do with. […] It was tough, and I think a lot of athletes go through it, a lot of people go through it even with retiring from a job. It was challenging, so I’m kind of glad now to be on the other side of things and to have processed that and been able to move on.”

Rachael believes that there are a lot of challenges, including mental illness, that can arise out of transitioning away from professional athletics, particularly when it’s not on an athlete’s own terms such as in the event of a career-ending injury. “I think a lot of athletes deal with depression, anxiety, [and] to some extent body image concerns, because you’re not training eight or nine hours a day anymore,” she said. “Your body, something that used to be such a finely-crafted tool, is no longer something that you’re prioritizing in the same way.”

Rachael expressed suffering from bouts of depression upon her retirement, which coincided with her decision not to attend medical school. “I just felt like I had nothing to work from and so I really struggled at that point. I’m hopeful that moving forward we can really start devoting some resources to making that transition because some folks don’t necessarily have access to the educational opportunities or they didn’t necessarily finish high school or college because they prioritized their sport. You kind of miss out on a lot of very basic life experiences, from something as simple as financial planning all the way up to very critical mental healthcare for acute crises.”

Rachael is passionate about developing digital mental health screening, prevention, and treatment tools in hopes of reaching those who cannot access traditional treatment resources and reducing the stigma associated with seeking help. “It’s a unique position to be in where I have the background from sports and now merging that with the research that I’m doing and all of the knowledge I’m gaining from being in school and learning from some of the world’s best at UNC,” she said. “The whole journey has just been amazing. It’s certainly had its ups and downs, but I’m so excited for where I’m at right now.”

***

The full recording of Rachael Flatt's Awakin Call is available here.

Sources

Mental Health & Stigma, by Graham C.L. Davey Ph.D., Psychology Today/ 2013

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/why-we-worry/201308/mental-health-stigma

9 Ways to Fight Mental Health Stigma, by Laura Greenstein, National Alliance on Mental Illness/ 2017

https://www.nami.org/blogs/nami-blog/october-2017/9-ways-to-fight-mental-health-stigma

Body Image & Eating Disorders, National Eating Disorders Association/ 2018 https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/body-image-eating-disorders

Emily Rose Barr is a DailyGood volunteer and a light-hearted creative who finds joy in simple pleasures. With a background in social sciences, she has a heart for connecting with others and sharing in their stories. When she’s not behind the lens or keyboard, Emily can be found hiking, ticking books off her to-read list (often with a cup of tea in hand), whipping up the best desserts, and playing with her sweet pup, Lyla. You can read more of Emily's works on her personal blog at ilyrose.org.

On Jul 1, 2019 Kristin Pedemonti wrote:

As a recovering anorectic, I really resonated with Rachael's story. I feel fortunate that the tools of healing inner narrative through the storytelling world's body of work has put me on a current path of sharing tools with others on how to reframe their narrative and thus see themselves as whole and worthy no matter what body size. Thanks again for another inspiring article!

1 reply: Aaron | Post Your Reply