Interviewsand Articles

Earning Humilty - My Story of Meeting Rollie Grandbois

by Richard Whittaker, Jul 8, 2021

Jemez Springs, New Mexico August 2007

“I have no idea,” the shopkeeper said, which surprised me. He’d just explained that his entire family worked in the studio together, right through that door at the back [he pointed]. His son, he explained, made all the ceramic pieces displayed around the shop.

“There’s a kiln back there?”

“Oh yes! My daughter does the cards and all the photos hanging on the walls.” And the cosmetics? His wife made those. “I do all the woodworking,” he said.

I’d picked up a blue ceramic bowl with a flashy crystalline glaze—tricky for a potter to pull off. “What cone do you think this was fired at?” I asked, thinking it might open a conversation. And I was surprised with his reply: “I have no idea.”

The response was oddly emphatic, as if to close that door tightly. I got the message and tried to let it slide, not quite feeling that I’d just been fed a lie. And even though nothing I’d seen in the shop had appealed to me, I went back to looking around, not quite willing to give up. Besides, I needed time to come up with another gambit.

It was a bright August morning and I had the shop all to myself. Since my wife and I were staying nearby, we’d driven past the place before on the way to town. To tell the truth, from the look of it, I’d decided it was best avoided. But this morning, I’d decided to go against my snap judgments. Besides, I needed a little break. So as an exercise, I thought I’d go out for a walk and strike up a conversation with strangers as the opportunity appeared. This required an effort to go against my usual tendency. To be candid, the idea of approaching strangers stirred up a little anxiety. So I thought I’d start with a shopkeeper. It wasn’t going so well.

Jemez Springs, about fifty miles west of Santa Fe, is tucked between red mesas along the Jemez River, a village of about four hundred. For about a week, my wife and I have been staying in an adobe compound nearby with my brother, his wife and a couple of his close friends. Having tired of sightseeing and group activities, I was now out walking in town. It was like prospecting, but instead of hiking into some hidden canyon or climbing desolate hills, all this involved was striking up a conversation with a stranger and paying close attention. Since I publish an art magazine, I figured I’d start off with something easy. Jemez Springs has several galleries and gift/craft shops. There were also studios open to the public, some of them belonging to potters in nearby Jemez Pueblo.

Although it was an easy place to start, I didn’t expect much. I’d developed an ambivalent attitude toward southwest art in general, a reaction to decades of commercialized exposure tending toward cliché. In any case, the place I was in did not feature much southwest art. The shopkeeper was keeping his eye on me as I stood in front of a framed photograph. He piped up, “My daughter took that.”

“Is it an inkjet print?"

It was another technical question. Only this time, it included a sly bit of provocation.

“I have no idea,” the shopkeeper intoned for the second time, enunciating each word with bizarre clarity.

This time, I couldn’t let it go.

“Well,” I persisted in a helpful tone, “was the print produced on a printer, or in the darkroom?”

“I have no idea,” he repeated as if to say, what is it about these simple words you don’t understand?

My candid response would have been something like, “Come on! You’re the owner. You’re selling these things. Your own wife and son and daughter are making them right under your nose! Are you blind?” But instead, I put it this way, “I guess you really keep to your separate kingdoms back there in the studio.”

“Oh no. We all work well together!” he said.

It was time to leave.

The Law of Influences

Driving down the road, however, I discovered my conversation with the shopkeeper was continuing in my head, and even picking up steam. Jesus, I thought. This guy really got to me. I realized that I was angry, and wondered why. But the next gallery was only a couple of miles ahead. Maybe all I needed to do was to engage with someone else. But what if the next person was even less congenial? Well, it would be interesting to see what happened.

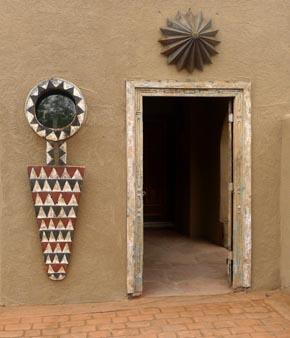

The town was a few miles behind me with Jemez Pueblo not far ahead when I saw the sign, Shangri La West, and pulled into a dirt parking lot. To get to the gallery itself, one opened a gate and walked along a high adobe wall and down a walkway, which divided in two directions. It was a little confusing, but I liked the feeling of this place right away. The door to the gallery itself, I found, was locked. So I walked over and knocked on another door—to a home, I guessed.

A white-haired, grandmotherly woman appeared at the door, smiling. She took me back over to the gallery and unlocked the door inviting me in. Indian artifacts were all over the place, on the walls, on tables and shelves.

“Is all this work from local artists?” I asked.

“Mostly.” Soon we were trading information about each other. Conversation simply began to flow and it wasn’t long before I was aware that my mood had completely lifted. I wondered what lay beneath the change—a sense of trust?

Her name was Andree. She spoke with an accent. She was from Belgium and lived in the adobe compound with her husband Rod, a former chemist, whom she met when he was stationed overseas in the military. They’d fallen in love at first sight and married. Later, Rod had begun to feel unhappy with his career as a chemist. Andree had taken a course in jewelry making. In the evenings, Rod started helping his wife with her projects. “I could tell he was really getting interested,” Andree said. He quit his career in chemistry and became a jeweler. They bought their place in New Mexico years ago and had begun an entirely new life.

The more we talked, the more interesting the conversation became. In fact, I began to think it might be a story worth hearing in more depth. Did she think they’d be willing to be interviewed? Why didn’t I ask her husband myself? Andree replied, and she left the gallery to get him.

While she was gone my attention went back to looking around the gallery again. Some of the pieces of pottery had quietly already made an impression. I got up and went over and picked one of them up and looked at it again, this time more carefully. There was something impeccable about it.

But it was only a few minutes before Andree was back with her husband, a lean, somewhat rugged looking man in his sixties, I guessed. As we shook hands, I could see that Rod had a reticent way about him, but I was too charmed to hide my good spirits. And in no time we were all three talking like old friends. At some point, I’m sure I must have marveled at the inner distance I’d traveled in such a short time. I left them feeling completely refreshed. I no longer felt myself a complete stranger in those parts. Now I had at least two new friends.

Far Side of the Moon

During the two weeks I spent in Jemez Springs, I drove past a sign along the road several times, a stylized eagle made from metal and painted cleanly: “Grandbois Studio.” Next to the sign a dirt road curved up a hill where no building was visible. This sign, too, had irritated me—another Southwest cliché, I thought.

So on the last day of my visit in Jemez Springs, I decided to drive up the little dirt road and find out what Grandbois Studio was about. This was another experiment in checking my preconceptions. I fully expected to find myself in a gallery full of stylized coyotes, cacti and Southwest Indian figures with blankets.

A hundred yards up the road, coming around a turn, two nondescript buildings came into view. Neither looked like a gallery. There was no further signage at all. No one was in sight and no art was visible. The building closest looked like it might be used for storage of some kind and the next one, a building of unadorned stucco further up the road, appeared to be a house, It was aligned so that its entrance wasn’t visible. What I was seeing was utterly at odds with what I expected.

Uncertain, I continued up the road, which led, finally, around the house above. By now I was feeling disoriented and a little like an intruder. Then I spotted an older man sitting alone in a canvas chair several feet from the house. He was looking at me with no hint of welcome. I rolled down the window, “Isn’t this a gallery or something?”

He continued to stare at me as my uneasiness increased.

“There’s a sign down on the road,” I said, in an attempt to explain myself. “And I was curious.”

At this he raised his arm, pointing, and said, “Talk to him.”

Looking past his outstretched hand, I noticed a work area some distance away. Underneath a canvas sunscreen, I could see a man who appeared to be talking on a cell phone. In the clearing that lay between us, a good number of stone sculptures lay scattered randomly in various states of finish. The entire area was strewn with chunks of stone—marble, mostly—it seemed to me.

I parked the car and continued looking around. A massive stone grizzly bear caught my attention standing off to my right. It was completely finished, beautifully carved, maybe nine feet tall. As I studied it, I couldn’t help being impressed. A face was carved dramatically on its stomach. Taking some time to look around before continuing, I noticed abstract pieces here and there, too, a real medley.

As my wife and I proceeded toward the work area, I could see the man on the phone, who stood toward the back, had seen us. He continued his conversation. He was a big man, six-three or so, and wore dark, wrap-around sunglasses.

We stood waiting and looking around at the stonework. Finally he finished his conversation and walked over toward us. “Where are two from?” he asked without ceremony.

“The San Francisco Bay Area.”

“Are you going to buy anything?”

This question was delivered so bluntly that, for a moment, I was at a loss for words. I was in decidedly unforeseen territory. As I was searching for a reply, the man in the wrap-around sunglasses took advantage of my silence to add, “Do you have a lot of money?”

It felt like a slap, and woke me from my inner scrambling as I tried to reorient myself. It was time to put my cards on the table. “I’ve got to be honest, we’re not here to buy anything. And we’re not rich people, either. I just was curious to see what was up here having looked at your sign down on the road.”

I half expected he’d tell us to leave, but he stood there looking at us and made no gesture indicating our business was now over. And so began an unforgettable encounter with Rollie Grandbois.

I tried to explain that I was interested in art, but in an old fashioned way. I even tried to say what I meant by that, stumbling over words like “authentic” and feeling a little like a buffoon. Behind his opaque sunglasses, Rollie listened as I ran on.

“I’m Chippewa,” he said, cutting all that short.

“We’re just staying down the road,” I said, not knowing where I was going with that.

“It’s ugly around here,” he stated bluntly.

“Ugly?” But how could a Native American say something like that about the land? Again, I was at a loss for words.

“You really think so?” Something instinctive told me that statement had to be challenged. “I think it’s a nice little valley here with the Jemez River and the cottonwoods.”

“I’m from North Dakota,” he said. Was it a way of clarifying the reason for his statement? I didn't know.

We stood facing each other a few feet apart.

Recalling this a year later, I don’t remember exactly how our exchange led this imposing man to begin a recital of outrages done to Native Americans by my ancestors, the European settlers. My wife and I listened respectfully.

“How would you like finding your grandmother’s skull in a glass case on display in a museum?” There was no possible reply, and I tried to keep from squirming. Wherever I was, it was a long way from where I’d been when I turned off the highway just a few minutes earlier.

His uncle—several of his relatives—had fought in U.S. wars. They were warriors. They had been honored with various medals for their service. It was brutal, war. Brutal. War is Hell. His uncle had not spoken of it for over forty years. Not a single word. But then, just a few days before, he’d spoken. “It was just like it all had happened yesterday,” Grandbois said. His uncle “could still feel the heat of the ordnance.”

Words did not suffice.

As my wife stood there listening, Rollie Grandbois, continued - his intensity increasing minute by minute. Were those silent tears coming down from beneath his dark sunglasses? I began to fear where all this was going. Had he been drinking? Was violence just a few minutes away?

How did I get myself into this? I wondered. But I was in it.

I’d decided to check out my bullshit judgments—and they were bullshit now, as I could plainly see! But they’d taken me up the road and now I resolved that, by God, I would stick it out even if I had to stand listening until the sun went down. And no, I thought, this would not end in violence. It would go where it would go, and I’d go there with it.

“But I shouldn’t talk this way,” Grandbois said, finally. “It’s not nice.”

Not nice. An unexpected phrase.

One unexpected moment was following another. It wasn’t nice to hold the feet of these white visitors to the fire. This guy and his wife hadn’t committed these atrocities themselves, after all.

And then, at a certain point, something shifted. I don’t know why. Perhaps we’d passed a test. Now Mr. Grandbois turned back toward art. He’d graduated from the Institute of American Indian Studies in Santa Fe. He’d been class president there. He didn't campaign. It just happened because of how he is.

“I just got back from Zimbabwe,” he added. “I was there on a Kellogg grant.”

This piece of information was so unexpected it landed in my awareness like car that had barreled through a stoplight. How often is the narrowness of one’s habitual thought revealed in a single stroke?

Now I was listening, no longer with anxiety, but with astonishment.

Rollie Grandbois told us about his experiences with the Shona People. He told us that out of the five hundred people in the village where he stayed, that something like three hundred and fifty were stone carvers.

“Do you know how I felt when I got there?” he asked. “I felt like I’d come home.”

Before leaving on his grant for Zimbabwe, Grandbois had done some research to see what he could bring to the Showna People. A friend in Colorado who knew the Shona told him that protective eyewear for the carvers would be the best gift. Eye injuries from flying stone pieces were a common problem. Grandbois brought, hundreds with him. Even so, he told us, one carver had suffered an eye injury while he was there - and later died from it.

He described many of his experiences, each more interesting than the last. I left feeling both humbled and grateful. This small account leaves much out, but there’s one last thing to share.

Grandbois was there with a group of Native Americans. As he’d explained earlier, he was always getting asked to be the spokesman in a group, not something he sought. He just had that quality of leadership. It was easy to see how this would be true. Grandbois was impressive, not only because of his physical presence, but because of an undeniable personal power. And because he will say what needs to be said. So he had been the one who did a lot of the communicating with the Shona as well as with the officials from the Kellogg Foundation.

Rollie Grandbois, Prayer for the Future, 1999, Texas limestone - photo, Friderike Heuer

The Shona people liked him immensely and, when it came time for Grandbois and his cohort to leave, the Shona gave them a celebration party.

“There were people from many different tribes there,” Rollie told us. But there was a small group who left an especially deep impression on him: “There were four of them, little people, San People.” These are the Bushmen Laurens Van Der Post has written about so eloquently and with so much love and sadness at their plight.

“When the San people looked at me, they could see right through me.” There is more in this world than one can really grasp. “The four of them performed a ritual for us,” he said, and began to imitate some of their movements. “I didn’t understand their language,” he told us, “but the energy of what was happening made the hair on my neck stand up.”

Later Grandbois asked a Shona friend what the San people's ritual had meant. “It was a prayer,” the friend had told him. “They said a prayer for your trip home. It’s the first time they’ve done a ceremony among us.”

As my wife and I prepared to leave, Rollie walked with us over to his house. More than feeling deeply chastened, I felt grateful for the impulse to put my judgments to a test. The supreme moment came when we listened to Grandbois' first-hand account of the intimate ceremony performed by the San people. To put it simply, I could no more have imagined such a thing lay ahead of me as thinking I'd see the dark side of the moon.

We exchanged a few more words as we prepared to leave and, as we shook hands, Grandbois took off his sunglasses. The face I saw was as beautiful as any I’d ever seen. Driving down the little dirt road back to the highway, I was humbled. And I knew I'd stumbled into the miraculous.

It was

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversation and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Jul 1, 2023 Christopher Goodwin wrote:

I recently got a stone sculpture by Grandbois at a local auction for a price too low to mention. Knowing nothing about the artist, I'm grateful I came across your essay here; it gives me a real sense of the artist. The piece I bought is only 20 inches tall, but it has a monumental quality to it, much like the man himself, it sounds like.Thanks for writing this and making it available online.

On Jul 14, 2021 Ruth Block wrote:

Thank you again, Richard, for once more nailing it on the head. I continue to catch myself responding from my own implicit biases. Life is such a learning curve.On Jul 12, 2021 SüSi wrote:

My first thought when you wrote about the shop keeper that kept stating he didn’t know the answer to your technical questions about his family’s artwork was, “Of course!†You weren’t asking anything of real substance. Maybe if you started talking about what you appreciated about the artwork, what the subject matter was about, observed how the light effected the piece, what stories the art might be trying to tell, how it made you feel. You might’ve received an entirely different answer + reaction.On Jul 12, 2021 Ed wrote:

American Indians, like indigenous people from around the world, are Star People. This story has many hints about true wisdom and understanding; that such eludes written accounts or the small talk of folks passin' thru. Mitakuye Oyasin..."We are All Relatedâ€.On Jul 11, 2021 Helen C. Gennari wrote:

Richard, thank you for sharing your experience of opening the door to a stranger that seems to have been so enriching, so worth the risk.In the later years of my life, I enjoy the opportunity to meet people I don't know, strangers who bring with them their history, their own mystery, and their unique way of sharing it. This is how several of my cherished relationships began. Oh, it's so worth the risk!

On Jul 11, 2021 Kristy wrote:

True connection is so glorious!On Jul 11, 2021 Lynn M Miller wrote:

It is so interesting that this conversation comes up now. I anticipate what it will be like "getting back out there again" as we gain some measure of vaccination and control with the pandemic. The last few years have brought a series of shocks. Biology, politics, and religion have all delivered previously unimaginable examples of what can happen in our world, and what passes for thinking, and the pent-up grievances that fuel powerful reactions on all sides. The stress of the pandemic reveled the weaknesses and fractures, as well as awe-inspiring examples of what we can accomplish working together. My world is not what I thought it was. So what is really here? Can I really commit myself to listening?Thank you for the photo of Prayer for the Future. Art speaks, and it is so powerful. If I read it correctly, the stance communicates so much. The head, turned up to the sunshine and the higher forces of the universe in a kind of serenity, but offering the ear for hearing, and the cheek, non-confrontational. The body, and hopefully the heart, is wrapped in loving protection,and holding an eagle feather fan. Eagle feathers are not taken for oneself, they are awarded for great effort, symbolizing mind, body spirit. Strongest, bravest, holiest. Right now, from what I can see, that is what I see. Thank you, both to you and Rollie Grandbois for this moment.

On Jul 11, 2021 Kristin Pedemonti wrote:

Thank you Richard for sharing your range of experiences when you stepped out of your comfort zone and conversed with strangers. Especially Rollie. May we strive to make no assumptions because there's so much we can learn when we connect.I feel blessed that strangers talk to me all the time and have thus encouraged me to do the same. Your encounters transported me to several conversations and encounters of my own..

A homeless man who reminded me of Santa Claus whom I asked if he'd like to share lunch. He agreed and for nearly 90 minutes regaled me with his heartbreaking and beautiful life journey in which horticulture saved him. We are still connected via email and more recently Facebook and LinkedIn♡ he has made a profound impact on me.

Another encounter came to mind, a woman sitting solo in a small restaurant in a small town struck up conversation with me, also dining solo. Though our views were entirely opposite, we had a deep mind expanding conversation connected over a commonality of being single women dining solo.

Always I seek to ask myself, what might i learn if I make no assumptions and connect. It's been pretty glorious. ♡

On Jul 11, 2021 abbe rolnick wrote:

What do I think--is exactly what the opposite of the article-- what do we feel, what door do we leave open to find the miracles. our seeing is not believing until we feel another's essence. All this helps as I try to find my way out of trappings. Exposure, openess, and a willingness to experience others... this bridges us together.On Jul 11, 2021 Lucinda L Plaisance wrote:

Thank you for the reminder that there are amazing experiences and people in unlikely spots, if we can only slow down to really see them and listen to them.On Jul 11, 2021 Nora wrote:

Awesome! It is amazing what we find behind the “sunglasses†of thosewe encounter through our life — provided we take ours off to reach others.

On Jul 10, 2021 Judy Kahn wrote:

Richard, what a beautiful story about the miraculous artists one can meet in and around the strange little town of Jemez Springs. All you have to do is search for them, something you have a flair for. I felt a pang in my heart remembering that time in Jemez and all of us there together.