For a lot of its history, the “road trip” has conjured predominantly white, straight, masculine images (see literature from Homer to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow to Jack Kerouac), but of course, that’s never been true. Women have always voyaged, whether to follow seasonal resources, relocate or migrate, work to make a better life, or to make art and dream. The road is also one of our homes.

It’s also true that “the road” may feel different to us, as women, and to each of us, individually. Gender, class, race, and sexuality complicate the myth of the “freedom of the open road”; though in that complication, fascinating connections blossom, too. Travel raises questions: How do we engage the unfamiliar? How does the unfamiliar engage us? What are our responsibilities as travelers? What wrongs, silences, and absences must we work against and speak into? What are we missing?

Elizabeth Bradfield, Rachel Eliza Griffiths, and Tess Taylor have each written books that hold poems and photographs. Bradfield’s Toward Antarctica uses images and Japanese haibun, a travel-inspired form, to share her work as a naturalist and guide on ecotour ships in Antarctica. Griffiths’s Seeing the Body holds poems and portraits of herself in transit through the American landscape, mapping her journeys through grief. Taylor’s Last West follows the path of 1930s photographer Dorothea Lange through California, alternating Lange’s historic photos with contemporary poems to show how Lange’s past chimes eerily with our own present.

These works ask: How do we explore the road with text and image? How do the photographs we use complicate the journeys we make? How can we remake and challenge a genre that has often excluded us?

Tess Taylor: We’ve each written projects that figured us as travelers, as documentary poets, as collaborators with the image. Liz, I love your wonderful Antarctica photos—the beautiful strangeness of ritual in them, of the unusual or forgotten sides of “tourist” travel—like decontamination showers. They highlight the fragility of the earth. Eliza, your photos challenge us to think about what a country is, where the roads through it go, where we feel our bodies do and do not belong. I love the way you weave your own body into these road trip photos in complicated, haunting ways. Now we’ve lived through a pandemic that has changed our notion of what travel means. What does travel even mean now?

Elizabeth Bradfield: Thank you, Tess. This first photo is one of my favorites from the book, because it’s so absurd. Taken in the Falkland Islands, a stop on the way to Antarctica. I love how it challenges who belongs in places of amazing natural abundance. Those albatross belong. The woman with nails and rings and an unspectacular camera belongs. I (science nerd, invisible photographer) belong, too.

I haven’t traveled during the pandemic. In fact, COVID was a slamming of the brakes for me, which was both good and bad. I used to work several months a year at sea as a naturalist/guide, which is part of what I investigate in Toward Antarctica. But I stopped all that in March 2019.

Stopping, staying put, made me both sad and glad. Sad, because I love “boat work”; glad because I needed to step back and think about how I might better align my values with the work I do.

Rachel Eliza Griffiths: What’s changed in the past two years, and perhaps longer than that, began with the death of my mother in 2014, where a certain kind of road trip ended for me and another began. After feeling disembodied and spiritually lost in grief, I forced myself to reengage the physical world, exploring my mortality and the imagination of that. Certainly, during the pandemic, the sensation of mortality has been very sharp for all of us.

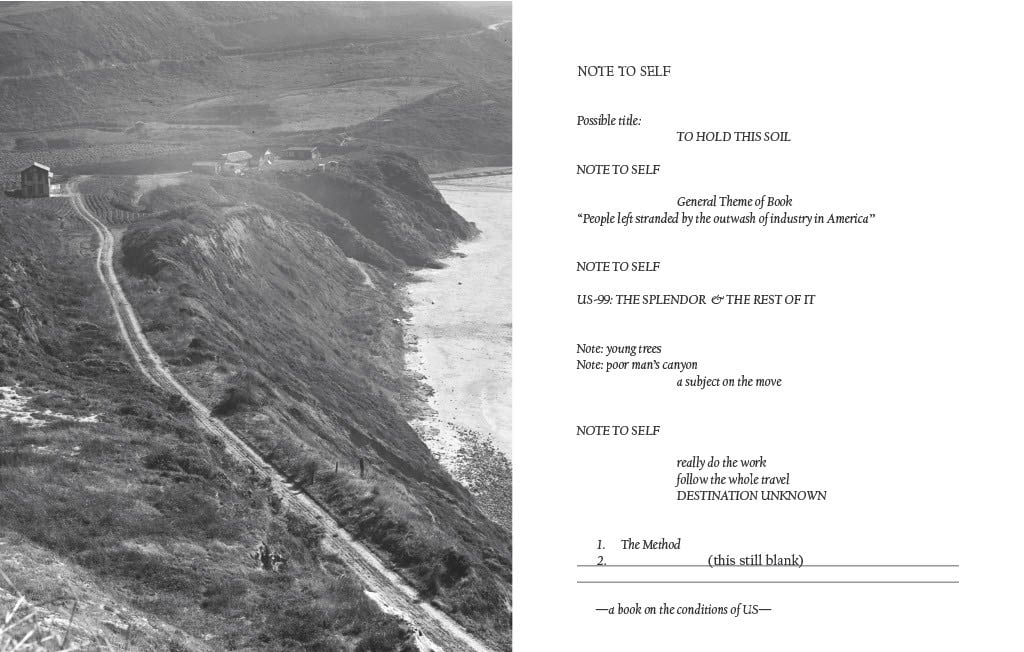

TT: In the years directly before the pandemic, I was traveling constantly—following the trail of Dorothea Lange through California. I went to places where she documented shelterlessness, migrancy, and climate change in the 1930s and ’40s and wrote her letters back from the present. Those issues feel so timely today. During those pre-pandemic years, I was a road warrior, on the road by myself or with an art partner.

Putting the book together later—my poems documenting Lange’s travel—I found myself using non-iconic images, images that could blend into some middle distance between past and present.

Lange was documenting migrancy and environmental devastation in a state where we are now facing those interwoven issues at dramatic proportion. I wanted to weave the collage in a way that problematized “then” versus “now” and “them” versus “us.” I wanted to use her to help us see that she is still challenging us to reckon with, and to recognize ourselves.

But then came this break—the pandemic. A stop to travel. Not a pause in the problems, but it was eerie when it stopped. At first it didn’t feel safe to travel and it didn’t feel safe to do activist work. I fell into the sheer domestic labor of caring for a family and children. My partner has lung issues: any travel felt necessarily forbidden. The conditions of my art-making shifted radically.

REG: Tess, this feels similar for me, as I think of how so many shifts have altered the conditions for art-making. These days, I often think about what my wanderlust gave me in the past but also, what else might it be? Sometimes I feel envious when I hear that a woman is going on a road trip because I realize I’m not strong enough right now to be the woman I was when I could go off and be alone. As I get older and have more obligations, it’s much more difficult to get behind the steering wheel and just take off.

EB: Yes, there’s more that needs clearing away before departure, or more that should not be cleared away, that should inhibit being “away”—I don’t want to be out of touch if a loved one is ill. And it’s harder and harder to step away from our digital lives, at least for me. There’s an expectation that everyone will always be reachable, and I don’t always want to be tethered to my email, particularly not if I’m trying to be fully present in the place I’m visiting.

And what you say about vulnerability resonates, Eliza. I also think about what feels safe or not safe when I travel, whether the danger is with bears or weather or people. I’m white, and probably am assumed to be straight, but my partner is visibly butch. We took a road trip through Georgia and Florida’s Panhandle this winter. As a couple, I am always aware of how visible we are. This past year, there was an increased vulnerability, a question of when we might cross from “other” into “hurt-able.” We didn’t experience anything terrifying, but the potential colored our time on the road.

TT: These questions of personal safety—and whose safety—are paramount. Especially now. I think of Lange traveling all those miles as a witness, as a member of the government, sent out to witness. We live in an era of such fracture. Who is documenting the breakdown? The one road trip I did take during the pandemic was born of environmental destruction. There was a month of fire in California from August to September 2020. Our kids’ lungs were totally inflamed. One day the sky here in the Bay Area turned red—a famous horrible day. As the sky held steady orange at 11 a.m., I found myself emptying the contents of the refrigerator into the cooler. I’ve never packed the car so fast. We drove east toward the Sierra. Ash was falling so hard that we couldn’t see the mountains as we crossed them. When we reached Tahoe, the air was so bad, it was 450 on the air quality monitor—50 is healthy, 100 is bad; 400 is off the charts.

We couldn’t even see the mountains. My husband turned to me and he said, “I want to go to South Dakota.” His family has a farm there. To him, ultimately, that family farm is safety. It would be good air. So we drove with the kids for twenty-three hours and we ended up on that farm. It was a stunning drive, across the iconic West, but we were fleeing. So much about that trip haunts me. It was actually the road Lange’s Okies took, but in reverse. As if we’d already used up the very California those migrants held out as a dream less than a hundred years ago. Lange was with me, but I was going away from California, not toward it. I thought about those people who have lived rolling in cars and moving on foot. I thought about tides of migration.

And I was also so aware of the privilege of having a place to which we could flee. This big midwestern family farm. I thought about what privilege it was to be in this white heterosexual marriage and this relatively normative-looking body while I was crossing this space. About a legacy that tied in whiteness and pioneerism. And I thought about how many people are fleeing those fires.

EB: Tess, what an intense experience—I am so sorry for you and your family! This resonates so much with what Lange was documenting: people fleeing because of a climate crisis. I wonder how your book, Last West, would have shifted if it had been written during this time. That reckoning of settler colonial history is so important.

In the guiding work I do, this is also a huge problem, and capitalism undergirds it by commodifying places, experiences, and (in some cases) people. We need to engage in a deeper grappling with how to ethically travel, both ecologically and socially. To reconsider how guides can help people meaningfully encounter and connect with new places and communities. In ship-based ecotourism, in particular, it’s possible to float through places in a ship bubble. I’d like us to do more to support and learn from the communities we travel among, to engage, particularly if it’s difficult and uncomfortable.

Part of my goal with Toward Antarctica was to pull back the curtain and show the working parts and tensions of the service industry behind the marketed product of expedition travel. In addition to whales and icebergs, there are logistics and engineering and staffing issues. Most naturalist-guides I know come to the field because they love animals, plants, places. Many of us question whether our work is helping or harming.

Chinstrap penguins alongside a bust of Captain Pardo, Elephant Island, 2011. This is the place where

Sir Ernest Shackleton’s crew waited months for rescue. A tiny island “between” the

Antarctic Peninsula and South Georgia Island, the seas around it consummately challenging.

(Photograph by Elizabeth Bradfield)

TT: Well, even without those terrible fires—though who can forget them?—the environmental cost of travel locally is newly visible too. I like to imagine that for some of us there’s been a power to rooting: in the first year of the pandemic, our collective stillness brought down emissions by something like two billion tons. That was only one of the many enormous revelations about our huge impact on the planet, and the huge inequalities between one another. And if we’re to really live with this reckoning, we need to change. How do we go “back to work” when we’ve just lost a million people in just the one country around us? I’d like to think that we’re all looking at our lives and thinking, What do I want? and also, At what cost?

Good Deeds

Then think of every song of love hurled at you & yours.

Recall how battered you were by sheer understanding

so that you might surrender. Not her being gone

but everything else. The world insists

you return. You go along with the house rules,

what the passage of sunlight means, a warmth

that is bold enough to burn the world alive.

I say I can’t remember how to be the same. I say

I can’t pretend to be that woman, the world,

or the love song you left behind your eyes.

I say that I am beginning to understand

the way my friends sing alone inside of walls.

—Rachel Eliza Griffiths

REG: Tess, this question of “What do I want?” repeats itself across so many genres for me. As I get older, I realize that the I is more of a we for me. One of the images that most haunts me is a self-portrait I created in Gloster, Mississippi, in 2015. I created this late at night after the Charleston Nine shooting, which would be only weeks away from Sandra Bland’s arrest in July. The shooting in Charleston made me so angry and sick I couldn’t rest. I was in the deep South, driving around in the dark.

I saw an American flag glowing beneath a streetlight on one of these haunted, nearly abandoned Main Streets I’ve seen in so many towns. I got out and set up my tripod not knowing what I would do. I wanted to scream. Instead, I found myself leaping and jumping inside of a memory, a long-held story about flying Africans. I literally wanted to lift my feet off of American soil because I couldn’t stand to think of a place that would allow a young white male to kill nine Black people in their own church and then be driven to a Burger King so that he could eat.

I was soaked in sweat as I kept crying, jumping, and trying to fly. The ground was so wet and hot, like skin. I was also trying to understand how I could care for and love America so much. This image became the cover for a memoir by Alicia Garza, one of the cofounders of Black Lives Matter.

It’s strange how such a personal, searing experience for me has shifted into something that feels much bigger than my actual moment of making the image. I look at the figure, which I know is me, but it isn’t the me who looks at it now and knows what else has happened in America since that summer.

EB: Oh, Eliza. I’m so glad that you were able to offer an image to others who were and are feeling the intensity of a body in a street. To have your image taken as emblematic must have been such a beautifully gratifying joy, even in the midst of pain. That you could have made an image that would be resonant for others.

I also think about the places where I’m safe because I’m going to leave soon. The places where I’m welcomed because you’re only here temporarily. I can be friendly for a little bit, weird and other as you are, whatever your weirdness, whatever your otherness. You’re not going to disrupt the status quo of this place long term.

That’s an odd kind of acceptance and is problematic in so many ways, but it’s also something that we, as artists and writers, can use—we can use that status of being transient and outsider, a bridge between here and what if, if we do so mindfully.

For me, as a white, middle-class lesbian, the questions that often rise up are: How am I culpable in this moment? How does my place in the social world I live in at home transfer to where I’m traveling? What other identities come to the fore when I’m away from home? How am I participating in these new relationships with a river, a coyote, a raven, a person? How is my otherness contributing to this moment?

TT: Yes, yes, to both of you! Listen: We’re talking about the road trips that we have made to make art, and I’m aware that part of what Lange was doing was photographing the car that breaks down in the desert, the people living alongside the road—which is very much something that is still happening today.

One of Lange’s pictures that fascinated me was this one that shows the notes people left in labor camps to get on to the next work site. It reminded me of the notes people leave in organized encampments right now so they can offer each other support. They are notes so people know when they can next get food at a church, when they might get a ride to take a shower or refill medicine. This is a really precarious form of travel; this recognizes the deep incredible needs people have—both in Lange’s moment and now.

In writing the Lange book, I thought a lot about the ethics, and how to tell this story. For me, part of the project was provocation: How is the past like the present? How can we use the past to help us see our own present more clearly? How do we find an angle—photographic or poetic—that helps us see the question?

I am not sure retaking Dorothea Lange’s photos now would have felt ethical. It might have felt like a cheap shot. But thinking about her legacy, and writing poems back from the places she’d been, using her as a lens on the messy truth of our very paradoxical America—for me, that felt opening and provocative.

EB: The question of how to deal with iconic images is so potent, Tess and Eliza, I’m glad you brought that up. In choosing images for Toward Antarctica, I pushed against the iconic or expected: the classic iceberg shot, penguin shot, leopard seal shot (shot itself as a term is problematic). I have a problem with those images. They rankle me. As if you can only stake your claim on the traveled route by “capturing” images that have been “captured” before, as if replicating those images proves somehow that you were not only there, but you were able to get the experience that had sold you on the trip to begin with.

For me, photographs were a way to push against all that. I wanted to make uncomfortable or difficult the visual digestion of a place that’s been visually offered with little friction. I wanted to put a little friction into my photos, I suppose.

TT: Liz, what I admire so much is that you use photos to problematize and critique the road/the destination/tourism as some Utopia. You’re critiquing a tradition that’s compelling but also incredibly problematic, and riddled with fraught violent histories. I like that so much.

REG: There’s so much you’re both saying here, particularly about the notion of resisting easy narratives and offering alternate space. For me to center my own body (and even more so as a Black photographer) in any landscape often feels dangerous, yet the roots of my feelings are inextricable to the birth and “dream” of this country.

Being on the road sounds so tempting, so privileged in a way (considering duties, such as steady employment and family obligations), but it’s a challenging and complicated thing. We’re saying that we deserve to own our journeys, our extended curiosities, without harm or violence being done to us. What can we control, and where can we witness discovery?

Recently, I watched a stunning Dorothea Lange documentary. Hearing her speak about her exhibition and her own mortality when she was in such physical pain yet working to the very end to create an extraordinary show, I think of how the word cost is brought up, particularly for women, the support of what is necessary to do that intense kind of work, how we can give it to ourselves. And how can we give it to each other? I wonder what you think about that, Tess.

TT: Well, I think one of the reasons that Lange was able to get these pictures—to really get those gazes—was that she couldn’t get them quickly. She couldn’t. She had polio. And she walked up to people slowly. This wasn’t the kind of thing you could ever do with an iPhone on the go. There was a deep transaction to set up those conversations.

Lange also had this eye for the necessities and for the sculptural accouterments of the body, like the laundry on the line, like the tent and the container. She was a listmaker. She wanted to compare your income against the price of beans and the price of gas. When people talk about her work, they also talk about her willingness to treat those subjects with dignity. She uses all the tools of portraiture, finding those moments where they’re caressing their faces or their hands are touching their faces!

Both her photos of bodies and of objects create a feeling of empathy toward the very problem of being in a body, of needing to live in dignity within your own fragile embodiment. Even in the lists of how much it costs for beans, or pork, or bacon—there’s this phrase: “what a body needs.” I love that.

Bending Light

“Because light rays always bend toward colder air, they bend downward near the Poles.”

—Captain Mac, Mary Morton Cowan

Oh, Mac—I’m bent

toward the flex of sea ice. Toward

aurora’s warp, but here I sit

six miles from your last home

in a town that markets light

as per the business guild. Nostalgic

light. Hedonistic, salty. Dune beam, bay

glint, bounce and spatter light

on prow and steeple, shin and shingle,

all the painters, painting. Or playing

on summer sand, air warbled by heat.

The trick of a superior mirage:

a ship afloat above what would wet it

in the seam shimmed and stretched between

sea-horizon and distant sky. Light’s

as close to spirit as I’ll venture. And

a beam through fog is guide

and caution both.

Mac, if light bends toward

the normal, if normal is

a line perpendicular to the boundary

between substances, air and water, now

and then, you and me, it’s

playing with the shadows one

of us has cast. Am I colder

or warmer? Are you the light?

Am I? The pole? Who bends?

Of course I’m bent. Listen: only

in a vacuum, between the stars’

wide scatter, does light go on & on

& always away.

—Elizabeth Bradfield

EB: I take photos, mostly, with the intention to document something. I don’t approach photography with any sense of myself as an artist. I use the camera for work: photo identification of whales and seals in field biology, an image I might use in a slide lecture, to remind myself of something.

When I decided to bring photos into my published work, I had to look with different eyes. My choices were based on emotion; if a photo made me feel, for some inexplicable reason, then I wanted to use it. I was less interested in technical perfection than emotionality.

REG: I’m not invested in technical perfection either, Liz, though I think we’re all too often encouraged, across genres, to feel that we have to sacrifice emotions in order to achieve technical fluency. I like to trouble these rules because they don’t exist as a this-or-that binary in my process. For now, the space of the lyric feels the most dynamic and useful in terms of my photography, poetry, and prose. I’m constantly experimenting with forms. My pictures are more narrative in nature than my poetry. In the past I focused on portraits, usually of poets and writers. After my mother’s death, I went inward. The solitary figure in most of my images, often masked or altered, exists as a response to the landscape around me. I would hope that, as with a poem, a person who is willing to see a number of meanings and interpretations can bring his/her/their own experiences and stories toward me with a sense of both intimacy and risk.

Many of my photographs are titled the way I title poems, and the use of the lyric “I” or “we” also occurs in the multiplicity of selves that appear in my images. Like with my poetry, I create images without needing to know where they “end” ––I just want to keep them––me––open in wonder.

TT: I love that question of how the I becomes a we, Eliza. Lange was very much after that we. She gathered quotes from individuals, but I understand her work more as collage. She moved the quotes she gathered under photos with great freedom. There’s a famous photo that seems to be from the Texas Panhandle in 1938. And the woman says, “This country’s a hard country. when you die, you’re dead, that’s all.” Boy, that sounds authentic. But the caption moves around in Lange’s work. We don’t really know who originally said it. It captures a drama, or myth, that she has been after. The quote doesn’t have journalistic truth. It has resonant truth.

All this makes me think about ethics: It is critical to seek out wholehearted practice. But you can’t always codify in advance what that is or write a set of rules in advance and have them be 100 percent right. That it’s partly in the doing, that the thing comes out, you know? There’s a mystery to creating something that hangs in generative balance.

By the way, I love this conversation. I wonder: What is next for each of us? What are we dreaming? How does the gesture feel different now?

EB: I’ve been largely consumed with collaborative projects during the pandemic, coediting two anthologies, both of which interweave text and art. Broadsided Press: Fifteen Years of Poetic and Artistic Collaboration, 2005–2020 came out in April from Provincetown Arts Press, and Cascadia Field Guide: Art, Ecology, Poetry will be published in 2023 by Mountaineers Books. Collaborating on these has been connective and inspiring. The Cascadia guide has offered a chance to think into how the arts and traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) are essential to a true “understanding” of the more-than-human world and how we might care for it more fully.

REG: I’m in the process of editing my debut novel. I’m closer to having enough photographs for a small book of pictures but I want to take my time. If anything, these pandemic years have helped me truly appreciate slowing down and allowing ideas and dreams to ferment without being rushed.

TT: My work during the pandemic has been slow, close to home, very small scale. But I found myself recently dreaming again. There’s a new stirring in me to assemble a project—a different, beautiful unfurling to let me know that I don’t think that travel is dead. I don’t think that our hunger to see and know, to interpret, is dead. I just think that we’re living with such awareness of the fragility of our bodies, and of the planet, and of how questions of justice are at stake in almost every motion. It really is an invitation to reinvestigate practice, at every level. There’s so much call to tenderness.

This conversation began in a panel discussion held at Sonoma Valley Museum of Art in 2020 as part of their series “Words We Travel: Poetry and the Road in Tribute to Ed Ruscha.”

Elizabeth Bradfield is the author of several poetry collections, including Toward Antarctica. Founder and editor-in-chief of Broadsided Press, she works as a naturalist/guide and teaches at Brandeis University.

Rachel Eliza Griffiths is a multimedia artist, poet, and novelist. She is the author of five poetry collections, including Seeing the Body. Her forthcoming debut novel, Promise, will be published by Random House.

Tess Taylor is the author of five collections of poetry, including Last West: Roadsongs for Dorothea Lange. She teaches at Ashland University’s low-res MFA and is a poetry reviewer for NPR’s All Things Considered.