Interviewsand Articles

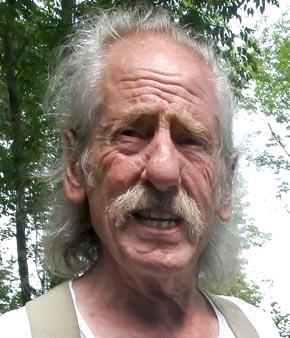

A Conversation with Davis Dimock:The Gift

A Conversation with Davis Dimock:The Gift

by R. Whittaker, Dec 7, 2019

There are people whose entry into one’s life is marked by something mysterious and recognized immediately, if without sharp outlines. A connection from some hidden realm is sensed, the sort of thing one hears spoken of as having met in another life. It was like that over fifty years ago, when my younger brother, John, brought his new friend, Davis, to visit me in my small apartment east of Los Angeles. My brother had won a scholarship to Pomona College in Claremont, California, and Davis was a classmate. I was two years older, married already, and like millions of others beginning their putatively adult voyages in the great pinball machine of life, profoundly unprepared for the responsibility.

In less than two years, not only would my marriage be over but, thanks to a string of utterly improbable events, I would meet Davis again, this time as a fellow student at Pomona College where, entering as a transfer student, I happily inherited more of my brother’s friends.

After graduation, I made my way to San Francisco where—skipping ahead a few months—I found myself roommates with Davis and another grad from Pomona, Malcolm Hall. We shared an apartment near the Haight-Ashbury District for a year and a half. It was a time of adventure and indelible memories, and Davis and I have remained in contact ever since.

A story occurs to me that’s revealing. I’d picked up the game of handball from an Irishman I was working for in San Francisco as house painter. I introduced Davis to the game, and a couple of times a week we’d walk over to Golden Gate Park and play on an outdoor court. I had the edge, but Davis kept improving. One day, we were well into our last game and I had a comfortable lead. I was sure I’d win, but somehow I began losing points. I tried harder, but to my amazement, Davis continued to close the gap. What was going on? Just bad luck? I dug in and somehow I lost another point. Then another. About then, I became aware of an energy emanating from Davis, something like pure will. And in spite of my best effort and the sure belief I was the better player, I watched the game slip away. It was as if Davis was showing me a hidden side of himself, as in “This is who I am.”

Life moved on. I remained in the Bay Area and a few years later Davis moved back to Vermont to help his parents. From time to time he sent me photos of his creative outdoor labors. His parents, both writers, had at one time actually farmed their 270 acres, but it was never their main focus. Davis was not interested in farming, either, but was always active on the land. After his parents passed away, he and his wife moved into the main house. As the years passed and new photos appeared, my curiosity grew to see for myself what Scrivelsby (the name Davis’ father gave the place) looked like after decades of the free play of Davis’ creative impulse.

It was the sad occasion of my brother’s death that propelled me, finally, to head for Vermont. After the memorial service, my wife and I flew to Boston and then drove up to Bethel. It had been over forty years since I’d seen Davis. It was a joy visiting with him and his wife Victoria Weber - who I'd first met at Pomona College - and, as we caught up, an uncanny shift took place. All the years in between evaporated. It was as if we were together again as roommates. The exact quality of my experience of being with Davis replaced my faded memory of it, something impossible to describe adequately.

Most of our hours of conversation were not recorded. Although Davis may have shared some of his history earlier, I’d forgotten much. That he was an adopted child, I knew. I’d forgotten the part about how, because of his father’s work in government, he lived in other countries before coming to the farm in Vermont. As a child, he’d lived and attended school in Puerto Rico, Turkey, Switzerland and England. Over the years, important visitors were a regular feature of life. At one point, Davis and I were walking near an excavated area where a huge rock was exposed. He mused, “Once, when both of my parents were still alive, I was down the hill when I saw my father with a couple of other men standing above that pit. It’s funny, but I never thought to ask them what they were talking about. One was very tall and the other one was very short. They were all looking down at it—my father, John Kenneth Galbraith and Milton Friedman.”

The photos included hardly capture the overall landscape, which includes a pond, gardens of herbs, vegetables and medicinal plants (Victoria’s specialty), stone walls, outbuildings and more of Davis’ stone work. Still, one can get a sense of Dimock’s careful, playful art labors.

He and Victoria carry on in a rich lifestyle of their own. The interior of their old farmhouse takes one back to an earlier era. Creative touches can be seen in every direction. Heat in the house comes from wood stoves and their water is heated by a large cast-iron, wood-fired stove in the kitchen, on which all the cooking is done. We sat inside to record the following conversation.

—R. Whittaker.

works: You have some unusual views about art and maybe we could start there. Would you say a little about that?

Davis Dimock: I just think of art as the juxtaposition of objects that I’m surrounded by. These are found objects, mainly rocks, stones, dirt, wood—the things I’m working with all the time. I try to put them in combinations that interest me. I don’t come to that immediately. I collect pieces and set them out, and then just observe them. I don’t think of myself as an artist, per se. I feel I’m an art-laborer. I do things with artistic intent. It’s just my nature; I’ve always been sort of “neat and tidy,” and like things in their place. Then I realized that their place is not necessarily a permanent thing. They can be moved around.

My mother used to say that as a child I was “sandbox-deprived.” The elements of rocks and the things I play with are for entertainment value, in a way. But I like the results. The thing I like about this the most is that I get to see it; I get to appreciate it at different times, in different light and in juxtaposition with other things. And there’s the wonderment about the space between the things I’m creating and what I could do to tie them together, or separate them—like making use of paths through the woods that are straight lines.

works: Would you say more about being an “art-laborer”?

Davis: Well, the people you interview—the potters, painters, scuptors and so on—they really set out to create things. I don’t do that. And I don’t think of trading or selling my art for anything. So for me, art is a process that gives legitimacy to my meanderings around. I move things. I juxtapose things, and people see it because there’s a road that runs through the middle of it [Christian Hill Road]. If every artist had a road running through the middle of their studio, probably their artistic intent would change, depending on the reactions of people. When people stop here and ask, “Are you an artist?” I say, “No. I’m an art-laborer.” A friend of mine heard me say this and she said, “Davis, don’t be pretentious. You’re an artist.”

works: But there’s something important to you about making that distinction. How would you put that?

Davis: I read this book by Jean Dutourd [Pluche, or the Love of Art] and it made me realize that art, for me, is an integral part of everything. And what I do is labor. When people ask me what I’ve done I never say, “I used to be a production manager for a dress company,” or “I was chairman of the planning commission.” I say, “I’m a laborer.” All of the “art” I do is task-oriented. I’m moving dirt that I want to get out of the way, for instance. Sometimes my best projects are ones where I remove something from one place to create something, and then use what I’ve removed to create something else. So, I usually have three or four different projects going on at the same time.

works: So you might want to excavate some area around your house because maybe you want a path, but you run into a rock. And then, “Okay. Now what will I do with the rock?”

Davis: Yeah. First I’ll see if I can get it out. Once Victoria (Weber) gave me a big set of rock chisels so I could break rocks up into more usable pieces—because a lot of what I do with rocks is dependent upon how much I can lift. If I can move it, and it will fit in with another project, slowly I’ll have another piece.

works: Can you say more about the role of labor in your own life?

Davis: I’ve always been a physical junkie. I’ve always worked out with weights. I taught Tai Chi for a long time. I’m very interested in exercise, and the kind of labor I do is exercise. That’s why I mow the lawns. The people who ride their mowers around say, “This way I’ll have time to go to the gym.” I say, “If you pushed your mower around, you’d be getting exercise.” You can think of it in different ways. You can do all sorts of things with your body.

So, I like the labor aspect of it. I also like the physics of moving large rocks. I like the fulcrum, the lever, the whole nine yards—and the fact that you can do it so incrementally. It’s like when I was living in San Francisco. There was an employment agency where you could go down and get a day job. Once I got a job working on the dock scraping the rusty interior of an old ship. Inside it, I couldn’t really see well, and I’m scared of heights. I was in there scraping it and then, when they brought in a light to take a look I was like, “Holy shit!” I’d been up very high the whole time. I learned from that that all I had to do to feel safe was touch the side of the ship and feel a connection.

With balance, I’ve learned to disregard my sight, and instead just use feeling. If you’ve got two rocks on top of each other and it’s a little wobbly, don’t keep your eyes open as you try to shim them. Put your hand on the rock and the shim under it, and you’ll be able to feel when it’s solid again.

The whole process of doing things, like the art labor, is a process of learning how balance works, how important it is, and that you don’t really need to grip something hard. You just have to know it’s there and touch it with your little finger.

works: Would you say that part of this process that interests you is exploring a deeper relationship with such overlooked parts of ourselves?

Davis: That’s a result of what I do. I don’t set out with any intellectual thing in mind at all. When I’m working, and when I’m really focused on something, as Victoria says, I just get blissful.

works: What do you follow? Because you follow something in yourself to go from step 1 to step 2.

Davis: It’s what I’m capable of doing. When I see a situation, like a rock, “Am I capable of moving that rock?” If I think I might be, I give it a shot. If I fail, okay, I failed. It’s the same sort of thing as when I was part of the planning commission [in Bethel, VT]. When people would congratulate me, that was sort of embarrassing. It’s more interesting when people told me I was doing something wrong. Then I wanted to know, “What’s up?”

And with rocks, when something doesn’t balance, I think, “Okay. That should balance. Why won’t it stay balanced?” Then I think, “Well, it’s because you’re using your eyes and this half looks heavier than that half.” But because of the shape of the rock, it would much prefer to lean the other way. So I found that by shutting my eyes, it immediately worked.

I had gotten the idea from Tai Chi. Sometimes we’d practice a long Yang form, like 88 steps or something like that. Sometimes we’d do it with our eyes closed, and it just made an amazing difference. Then sometimes we’d do it with our eyes closed and backwards. It would take me a hell of a long time to be able to do that. But I felt that maybe I could somehow extrapolate the balance concept from Tai Chi.

works: You know, people don’t talk about physical sensation. We talk about thought, maybe emotion, but does the word “sensation” have much meaning for you?

Davis: I feel the endorphins, and I feel calmer. For me, that’s a good thing. It’s akin to the euphoria thing. When I started feeling that, the first thing I thought was, “Well, this is because I’ve done something and I appreciate the result.” Then I realized it wasn’t that at all. It was just that I was focused. Art, and the labor I do, helps me focus. It helps me concentrate. I don’t set out to concentrate, but I’ll find myself in a position—and going deaf helps, of course—but people will come and be standing talking above me in the pit, for instance, and I’m totally unaware. I’m just so enthralled, and to take away that pleasure and interject verbal conversation is not a trade I want to make.

works: Okay. Through this physical labor, you can move in the direction of a kind of state where you’re enthralled or present or something.

Davis: Initially, I’ll make a decision. It’s like those big rocks you saw in the pit, the large ones. I uncovered them and sort of adjusted them. Then I thought, “Well, no way in hell am I ever going to get these out of this pit. This is the end of the project.” With something like that, I lower my expectations. “Okay. This big rock is not going to stand up like Avebury. Instead, it’s going to be lying here. Lichens and mosses are going to grow on it. I will clean out underneath it, so people can see I’ve been here. And that’s something I want, too. With a lot of the stuff I do, I want people to say, “He did this.” It’s mainly because I want them to be able to say to themselves, “Hey, I could do this. I could go home and dig a hole. I could stack some rocks.” Then, when people go and do it, that gives me great pleasure.

A friend of mine, David Brandeau, has all these standing stones around at his place. He said, “I did this because I got inspired by you. I thought, wow, Davis has stumbled onto something here. There are a lot of rocks in the hills of Vermont. That’s something we can play with.” He has machinery, so he was able to put big rocks into an Avebury circle.

Something else people who see this place appreciate is the fact that this guy, this adult, has spent time doing this. So it’s okay for me to go do it, too. Like children will come here and look at things. “Mom, what is this stuff?” Then mom or dad asks me, “How do you normally interact with kids?”

I say, I want to show them it’s possible to spend their time doing something aesthetic, doing something artful, and it’s just as good as becoming a junior capitalist. It’s going to give them just as much pleasure, and it’s something that others can enjoy, too. That’s why I like my art with the road running through it, because people see it all the time.

works: Yes. Christian Hill Road runs right through the middle of your farm.

Davis: And it’s important because that’s how I make contact with people. It’s just much more enjoyable for me to talk to people about art and balance and things like that. The development review board and the statutory language that incorporates your town plan and stuff—I mean, I can do that, but it doesn’t give me a sense of fulfillment. Whereas talking about art, and talking about art labor, does. I don’t even try to persuade people to be artistic. I just say this is available; you can do this. And they see all the different stuff. And the kids say, “Well, gosh, adults can do this sort of stuff?”

It’s permissible. One can goof off. When I first started doing stuff here and moving some of the bigger things, especially up in the woods, people would ask, “What about all the labor this involves?”

I said, “It’s hard work, but I don’t mind hard work.” I like getting really tired and sweaty, and I like trying to figure out how to move large rocks, or where I’m going to dig. It incorporates physics and all sorts of tidbits I remember from my academic years.

works: And sometimes you describe this as play instead of work. So, talk about work and play.

Davis: Well, some people have asked me to recreate things I’ve done here in other places. I don’t want to do that. Playing is something that comes sporadically. It’s nice to have your playground someplace close where you can go to it if you so choose. And you can work on one or another project. I don’t think I’d get the same pleasure out of creating one of these things somewhere else.

works: You’re not interested in getting money out of this, either. Right?

Davis: No, no. That seems too complex, and a whole different ballgame. I don’t want to make a living from doing this. I’ve got a living.

A guy came here once from some outsider art magazine. He was taking pictures and he asked, “Do you do anything else?” So, I showed him some of my drawings. He said, “These are great. We could use these.” I told him I didn’t want them out in the world.

It seems pretentious to think of myself as an artist. I think of artists as people who are going through the angst of creating stuff, and then the angst of getting a gallery to show the stuff, or sell the stuff. And I don’t like capitalism. It’s depressing. By just creating something on the land, my payment, my pleasure, is when other people spontaneously stop and look at it.

works: Does the word “love” come into this?

Davis: I’m not sure what “love” means, so I can’t answer that question. I’m not sure what faith means. I’m not sure what magic means. These are terms that are applied to my things quite a bit. I get it that the person is giving me a compliment or saying this is reaching some part of the psyche or subconscious.

Some people will come and look and listen to me drone on. Then, at the end of the walkabout, they’ll say, “You know, Davis, I never talk about this stuff with my wife or with anybody, and here I am talking to you about it for a whole half hour.”

I think that the freedom my stuff creates is not so much from the stuff itself, but from the fact that I did it. People look at all the work, the gardens and the lawn, and they say, “You did all this?” Then there’s the “Why?” And I always have to say, “Don’t have a clue.

I just enjoy it.”

So, I think my mother’s seeing me as being sandbox-deprived is correct, in a way. I think of art as a way of playing. And now, with all these pop-up art things going on in Vermont, I think it’s a valuable counteraction to the craziness of our times.

works: You’ve mentioned freedom. What does freedom mean to you?

Davis: The father of a friend of mine, Vince Fago, who’s dead now, was a cartoonist. [Fago had an extensive career in cartooning. He moved to Bethel, VT, in 1968.] He was very idiosyncratic and wore these huge glasses. I knew his son, and I knew Vin real well. At his funeral, I said, “Vin Fago was a free man.” That really resonated with the people who knew him. I think it’s easier to experience freedom through art than it is through political science or something like that.

You have the freedom to juxtapose things, and why not try it? And if I’ve got a rock that’s been in one place for 15 years, why not just pick it up and transport it to another place? But explain to the rock why you’re doing it. “I thought you might like to look at something different for another ten years.”

With some people who come here, I’ll give my spiel about the artistic sensibilities and the freedom that surrounds us; it’s a freedom of being able to do something. I give permission to people to do this. I view freedom as permission, because if I think of freedom in political terms, it’s like faith; I’m not really sure what I mean.

Vin was free because he didn’t really care about anything other than his cartooning and his writing. He did all sorts of cartoon drawings. When I was trying to raise funds for the town hall here, he did a drawing of the town hall with all the citizens as mice. They were running around and doing different things, and he thought nothing of that.

As I told you earlier, after graduating from college in 1967 and doing my Conscientious Objector service, I was in San Francisco wondering what to do next. I literally thought, “Everyone talks about this retirement thing with such gusto that I’m looking forward to it. Maybe that’s what I’ll do now! I’ll just retire.” And I did. I’ve worked for people doing X, Y or Z, but other than working for Foxy Lady [founded by designer Karen Alexander] and for the Haight-Ashbury Project, I’ve never had a job, per se. So, that’s allowed me to feel free. I’m not tied into the constricts of making a living.

I realize I’m privileged, and I’ve been able to have this philosophical concept without ending up homeless. But I view freedom as not being tied up with what’s expected of me by society or what others expect of me, but being able to do what I, myself, think I should be doing.

works: I know that at several points in your life, you were faced with some big choices. And what I’ve seen is that when you look at something you’re faced with, and something in you doesn’t agree with it, you just don’t do it.

Davis: Correct.

works: In other words, from way back, you’ve had something like a compass, and it has to line up.

Davis: I think that’s my instinct. That’s why I’m working so hard to understand the concept of instinct and intuition, and how to make intuition more understandable so I automatically do things. I’m getting better at that, because now, whenever I have a feeling of intuition, I act on it immediately—especially with this concept of kindness. I just go with it.

works: So going back to Andover. You’d been accepted, but they said you’d have to repeat your freshman year. You said, “No way!” Then you’d been accepted to Yale, but when you saw New Haven, you said, “Sorry. I’m not going here.”

Davis: Some people would say that I make decisions based on idiosyncratic whimsies, like, Why didn’t you go to Yale? I just didn’t for that reason. I make lots of decisions based on sort of peripheral things or on things that just wouldn’t fit in for me.

works: Well, you call them “peripheral” but maybe that’s because you’re living in this world where you know they’ll be regarded as peripheral. But the thing is, something in you said it counts.

Davis: In Britain, they had this cartoon, Where’s Waldo? They show a big picture and Waldo is in the picture somewhere. For me, art is Waldo. I’ve found it. There it is. Let’s do something with it! When I get the idea for a project, I don’t see it in its completion, I just say, “Wow, I found something I want to do.”

Victoria will say, “What are you so excited about?”

And I’ll say, “Well, I’m going to move this rock over here, or I’m going to dig this hole!” And that process of discovery—finding Waldo, finding an aesthetic juxtaposition of shapes and forms—I really enjoy.

I used to have stuff stored away in the barn. I’d walk by it every five years and say, “Wow. Look at that stuff.” I liked looking at it, and finally it dawned on me, well, if you like this stuff so much, put it outside where you’ll see it more often! Now I see it from different directions, juxtaposed with different things, and more ideas come from that.

Sometimes freedom is doing incomplete things. You just start the ball rolling and see where it ends up. I won’t do something if it’s a Sisyphean task, like if I roll the rock uphill and let go, it’s going to roll back over me. I’m not going to do that. I’m not going to go to Andover and repeat my freshman year, and no, I don’t want to go to Yale because New Haven doesn’t look like a place I want to spend four years in.

Even when I went to college, I was a lousy student. I didn’t try. It wasn’t until my junior year when, all of a sudden, I thought, “I’ve got to graduate from this place!” Then I switched to English literature. My senior year, I had nine literature courses. But I could talk about literature and not feel like I was an idiot. And occasionally, Erickson (a philosophy professor at Pomona College) would say, “You can understand Davis better if you realize he thinks he has a sense of humor.”

I found that freedom meant I could just go with the flow as long as I was polite and didn’t upset people. Those were my criteria. I’m a big believer in politeness, and I view all my art installations as being very polite with one another, acknowledging of one another and tied together. I do all my art in a four acre, area. I think of the stuff I do as calming and polite, and I will sometimes converse with my little towers.

works: In the realm of intuition, or perhaps of dreams or visions, anything you’d care to reflect on?

Davis: It’s just that those things resonate with me to a greater degree. Emotional thoughts, and thoughts about art that come from my instinct and my intuition, I trust more. I don’t trust my brain. I don’t trust anybody’s brain that much. I don’t trust the human condition of verbalizing everything. That’s why I like numbers so much. And Charles Manson liked numbers.

works: And you met him, right? [yes] Why don't you tell that story.

Davis: I was working for the Haight Ashbury Research Project in San Francisco as part of my Conscientious Objector status. I hadn’t gone through the angst of Vietnam, as a lot of people had, because I just knew I wasn’t going to go there. When I applied for my C.O. status, I said, “As a human being, I refuse to kill another human being, and as an American citizen, I refuse to have any part in any of our transgressions in Cambodia and Laos.” Then some people from the military came and queried me more. The thing that finally shut them up is when I said, “I am not going to sign a contract with you folks so that somebody can tell me I have to go kill somebody. I know enough about contract law that I refuse to do that.”

Their response was, “What are you talking about?”

I said, “When you sign up for the service, you’re signing a contract, and I’m not going to do that.” My argument of just not wanting to kill people wasn’t enough for this thing.

I went for my physical in Vermont with a busload of 27 Vermont farm boys. They were all excited about going to Vietnam, and out of those 27, 25 were excluded for being physically unfit in one way or another. There were only two of us who passed. During the exam, when we were all naked, the only thing I did that might make people think I was crazy is I wore my cowboy boots with bells on.

I was healthy enough, and they asked, “Why won’t you go?” I tried to explain, and they said, “Well, you’re going to have to wait here.” So I had to wait for a day in Concord. People from Boston came up to interview me, and I talked to them for about three hours. A lot of it was because in the process I was asked, “Do you know members of the SDS?” and such, and I did. I’d never been involved with those groups, but I knew some of the people.

Anyway, I got the C.O. status and part of that was I had to find some acceptable work. I worked for Goodwill. Then a friend told me about the Haight Ashbury Research Project. So, I wangled with different people to make myself creditworthy, and I ended up working there. One of my duties there was to find hippies that fit the categories these different professors were doing studies on.

works: At the clinic?

Davis: Yeah. So, I just happened to bump into Charles Manson. I found out he kept a journal and I thought, “This guy could be valuable to them.” He was more than willing to talk ad nauseum. He was a fascinating subject for the people at the research project.

works: You ran into him on the street?

Davis: That was basically it. One of the places I’d go to find people was this place at the end of Haight St. by Golden Gate Park. It was good because there were always people going by. The way we lured people in to take this battery of maybe five psychological tests, was to pay them a dollar an hour. I guess a dollar an hour was something in those days.

So I was talking to somebody about the research project and this guy overheard me and he turned out to be Charles Manson.

He asked, “Do you play pool?” So I played pool with him four or five times. While we were playing, endless people would be coming to talk to him—and they were all females. Here was this guy who, as was so evident to me, was a misogynist and a jerk, and yet all these people were drawn to him. That just fascinated me.

He was enamored of the whole realm of psychology. So, he wanted to go there, and he brought his journal. When the head of the research project, and the others, saw his journal, they all said, “Wow, this guy would make a perfect subject.”

works: You’ve had an unusual life, and a big part of it is the family you grew up in. Your adoptive parents were writers and academics. Would you be at all interested in giving us a little snapshot of them?

Davis: My father was a political scientist. He was assistant secretary of Labor under Frances Perkins. My mother was a good friend of Eleanor Roosevelt; they knew each other well. Later my father went into academic work and taught at the University of Chicago, UCLA and NYU, and did things abroad.

My mother was a writer as well. She’d won the Baldwin Prize. She worked for the League of Nations in Geneva in the mid ‘20s. She was the first graduate of Bennington College. So they were both writers and they worked together; they edited each other’s work.

As a child, that’s what I thought people did; they wrote books. I was always amazed when you’d bump into an engineer or somebody else. I’d ask, “What have you written about it?”

All that affected me in such a way that, now, I’m a total Luddite. In college, I never typed a paper. I would hire a friend to type it for me. One of the professors, a religion teacher, finally said, “I give up.” Because I just refused to do it.

I wasn’t revolting against my parents, I just viewed cursive writing as being closer to my soul. I view typing as part of why there are doctors now who don’t know how to tie a knot. And my father, literally, couldn’t do cursive writing. My mother finally said, “You’ve got to start printing your notes.”

So, growing up I was around people who made a living doing things that I didn’t see other people doing. In my mind, that gave me freedom. I just knew I was not going to do a work-my-way-up-a-ladder path to some goal. I wanted to enjoy life. I wanted to do things that were more tied to my physicality. I remember once, when I was sitting in Oakland, somebody from Pomona (College) came up and said, “You’re the only guy I know who has kept exercising.” But I’ve always done that. And the kind of art I do is exercise, too. For me, it’s just more tied in with reality than the intellectual stuff.

Even though I was valedictorian at my prep school and got into Yale, when I went to Pomona, I realized, “Holy shit, man. I’m the dumbest guy here.” I wasn’t chagrined by it. I wasn’t even feeling bad, but I thought, “Boy, these people are on a different planet.”

works: I think you’re true to something in yourself—and I mean rigorously, but not because you’re trying to be rigorous.

Davis: It’s just akin to me. For instance, I used to have difficulty getting up in the morning. I’d think, “Should I doze another five minutes?” I slowly discovered that this indecision was just exhausting. So, perhaps ten years ago, I just stumbled on 6:52 a.m.

works: You mean, that’s when you get up?

Davis: Yeah. Period. I don’t have to think about it. I just do it.

works: That’s fascinating, though, to be able just to make a decision and stick to it.

Davis: Yeah. It’s just from some resource within me. And in my art labor, if I have an idea to do something, I do it. I might add or change it, but I’ve discovered that until you have the pieces out on the table, your mind is not totally taking in all the possibilities. You have to have the pieces on the table. So, that’s what I try to do with having all these different little projects going on at once.

As I was telling you with that huge pile of rocks I had—and I moved probably 800 wheelbarrow loads of rocks—it got to the point where I’d look at a rock and I’d know which of maybe five different projects I’d use it in. I would meditate on that rock as I pushed the wheelbarrow along.

Normally, you pick up a rock up and switch it around—How does it fit? What if I turn it over? But when I was moving rocks constantly, I could pick up a rock and immediately put it into place, and it was perfect.

works: The word “alignment” comes up. Something happened where you just knew where that rock would go. That kind of alignment is not a place we know much about.

Davis: I facilitate what the rocks want to do normally. I’m a human being, and I can pick things up and put them in a wheelbarrow. I can fulfill their wishes. Lots of times, I’ll think about my rocks like my stuffed animals. I personify all that stuff.

Victoria says it gets too complex sometimes, because I’m so much into the game, or whatever it is. But that’s how I think about nature. I’m part of nature, but I’ve got this brain that keeps me away from nature. I try to erase this obstruction and just go with the physics of the pieces, just go with the flow. I don’t think about the flow.

So, when you have an idea, do it. When you have an idea to be kind, do it. Don’t think about that stuff. If you’ve ruminated on it and feel that it’s probably a good idea, then it is a good idea and go do it.

But I only feel these things about positive stuff. I used to include negative stuff, too. But I’ve given up on negative stuff, because it’s not in balance. It’s too exhausting. The work I do regenerates my enthusiasm, my energy; it doesn’t dissipate it.

works: Listening to you, I want to say this is really being alive.

Davis: That’s what physical labor is for me. It’s being alive and using your body. That’s why modern medicine—two artificial hips, and a band to keep my hernias in place—is just miraculous, because it continues to allow me to use my physicality. And the use of physicality dampens my mind some, which is full of thoughts that don’t come to any good conclusions.

works: Most of us live in our thought way too much. We don’t get taught how to come down into the body.

Davis: Plus, when I come down into my body, then concepts such as balance are more available. I don’t trust my mental constructs, in terms of emotional things, as much as I do my physicality. In mental constructs words, unlike numbers, can be defined in all sorts of ways: Time flies like an arrow. Fruit flies like a banana. The meaning of numbers remains the same, and I extrapolate that to balance and to holes in the ground.

At a (Bethel, VT) planning commission meeting, people would come up with ideas and yet no one would resolve anything. So it would go on the agenda for the next meeting. But when I was the Chair I said, “No more of that!”

When I dig a hole or when I balance a rock, I feel like I’ve accomplished something. Out in the world, I know it’s probably not regarded that way, except by some people who come and see what I’ve done, and immediately react—like the women who cry, or Ethan Hubbard.

The first time I met Ethan, I was carrying a log down the road. I had it on my shoulder and it probably weighed 250 pounds. But with balance, you can carry a heavy thing. I heard a car come up behind me and I thought, “Uh-oh, this guy’s not going to pass.” So, I continued up the road until I got to our house where I put the log down. I turned around and there was Ethan, who I hadn’t met. He just looked at me and said, “You know, that was one of the most primitive things I’ve ever seen in my life.”

Victoria’s mother, who I like, is a Republican and she told me, “You belong in the 13th century.” At Pomona, after I tried to drop Economics, I went and talked with Salvatore Grippe [his art professor]. He said, “Davis, you should drop it. In fact, Davis, you shouldn’t even be here. Why are you here?”

works: That’s pretty amazing. Did you feel like he really saw you?

Davis: Well, he really saw me. After my sophomore year, I got to the very bottom of the Pomona scale of “if you don’t shape up, we’re shipping you out of here.” I went to Grippe and asked, “Could you give me a B instead of a B-?”

He said, “Well, let’s do some work.” He gave me some little projects and then he talked to me for a long time. Then he said “Your art is the most primitive thing I’ve ever seen.”

But that primitiveness that he spoke about resonated with me somehow. I have some sort of primitive survival view of the world, and I do my art in order to put up talisman ways of feeling comfortable with my environment and feeling good about myself. Art seems like a valid pursuit to me, and the combination of labor and art was just perfect for me.

works: In this culture, the men and women who do the labor are not honored. I had an experience of volunteering once in a restaurant as a dishwasher. I was using their old industrial machine. There were tons of dishes coming in, and so I’d be falling behind. But there was a sort of all-purpose kitchen guy there as a backup, Juan. When things got seriously backed up, Juan would just step in and the dishes would be flying. I’d think he was going to break them, but he never broke anything. In five minutes, he could do 30 minutes worth of work. It was unbelievable. Afterwards, I realized that Juan was a master craftsman, and I knew that no one would ever honor that. It bothered me.

Davis: A neighbor did construction work over at Dartmouth College, and one summer they were refurbishing a building that used to be a hospital. They were changing it into classrooms. So, I worked with him and did probably about a hundred rooms. You did the same task over and over and over again. I was working with these sheetrockers and other guys, and we’d all quit at four. Actually, they stopped at three and dicked around. I’d watched the work, so I could see the order in which they needed tools. So, I went around organizing their tools. I did this in my little quadrant of four people.

The next morning these guys said, “Who the hell has been moving my stuff around?” My neighbor, Randy Coke, who was the boss said, “Davis was doing this because he didn’t want to sit around and talk. He wanted to be doing something.” Then when they got to work, they started saying, “He’s right. This should be here and this should be there.”

In the process of my bringing this order, I saw that they seemed to take more pride in their work. Then the workers said, “We should have Davis do this on the whole floor and clean up everybody’s tools.”

So, that’s what I began doing. Then they’d all say, “Wow, this really looks great! I can find everything!” Someone had observed them and facilitated their work, and they were just much more…

works: And in doing that, I’d say that you honored their work, too.

Davis: And they responded to that. Our floor got done before anybody else’s. Essentially, I paid enough attention to see all the elements of what they were doing. They weren’t just putting up sheetrock. They were artists creating something, and I wanted to facilitate that.

With my art here, I get double pleasure. I get the pleasure of the process as well as the end result. I remember Sir Huggins, a knighted gentleman from England and a friend of my parents, came here and looked around. He said, “In England, Davis, it would take five or six people to do the work you do. It’s just amazing how you’ve integrated everything.”

So, in my sandbox I want to integrate things, and when I do, I realize, “Wow, there’s a connection between this element of physicality and my mental state.” A little dialog of mine is, “What are you doing with your life?” And I answer, “Well, I’m trying to figure out which end is up.” Basically, this stuff helps me decide which end is up.

For me, when I’ve created something that’s beautiful, that’s honoring my surroundings. When I help people organize their sheetrock tools, I’m helping them do their work. So, I feel aesthetics is something that we should all be doing, and if we all did it more, we’d have less time to fuck up. And in my opinion, as a culture, we’re really fucking up because we don’t do enough art. We don’t honor it, and we don’t honor the sheetrockers. A lot of labor is stultifying, you know, but I feel comfortable with labor. I respect laborers. I respect the “common man” and his work—and everyone who has worked here.

There was a guy who worked on our barn foundation, an Abenaki Indian and an alcoholic. He had sort of a chip on his shoulder, but I bonded with him immediately. I really liked the guy, and we talked about all sorts of stuff. At the end of the job, I said to his boss, “Mike is a great guy and I really enjoyed working with him.”

He said, “Davis, Mike was on his very best behavior here the whole three months. It was amazing.” Somehow being around me made Mike different. He did the concrete work and was really smart on that. By my acknowledging his work and talking with him, he became a real sweetheart. After the job he brought Christmas wreaths and baskets to us that he and his wife, an Abenaki basket maker, had made.

I think the art allows people to feel that way. A hole in the ground is not magic. It’s a lot of labor and most people respect work. My father bought into that, too. He was elected to the state legislature. People asked him to run for the legislature, and here in Vermont you had to switch to being a Republican. So he did, dutifully. What got him elected, some people say, was the fact that he’d once single-handedly loaded 17 dump truck loads from one of our pastures. And so, rather than campaigning on “I used to be undersecretary of Labor,” etc., he said, “I loaded 17 truckloads in one day and I really appreciate how much work is involved in the life of our farmers and workers.” That got him elected.

works: It reminds me of this poem [w & c #34] by Red Hawk (Robert Moore). Basically he says that when man has power tools, he loses touch with the natural limits of his body and suddenly he can bring mountains down. And then, without some contact with conscience he’ll behave recklessly. To quote, “Either he respects all things for their dignity and grace, or beauty disappears from the world without a trace.” I know it spoke to you.

Davis: I remember reading it and feeling it’s exactly right. It’s like an AK47. Boys have to use their toys. That’s why I don’t like technology. It allows boys with their toys to find other boys with their toys and think that they’re a movement. And yet, my friend Jedidiah up the road has Bobcats and skidders. When a big tree came down on the road, it was great to have a big machine come and pick it up. So, I appreciate the mechanical things, but I just don’t think that anything that allows humans to do things more quickly is a good thing. People don’t think enough about unintended consequences.

works: I remember a story. This must go back a few years. A neighbor of yours wanted to dig out a basement and asked if you’d be interested in doing it.

Davis: Yeah. A neighbor was building a house. They’d done the excavation and then built a retaining wall. Then they decided the excavation should go deeper, but they couldn’t fit the backhoe in so they were going to have to do it by hand. The construction boss asked, “How are we going to do this?” The owner said, “I know somebody who might be willing to do it.” So, I worked for 3 days digging it out, and Carl paid me $7.50 an hour.

works: I heard he offered you more.

Davis: And I wouldn’t take it. Initially, I said, “I don’t want to be paid.”

He said, “Davis, I have to pay you.”

I said, “Okay,” and I named a figure—the most I’d ever earned, $4.00 an hour from back when I worked on the interstate, time-and-a-half.

Carl said, “It’s worth $20 an hour to us.”

I said, “I can’t do that, Carl. You’re my friend. I don’t want to lose my good karma.” Because I feel that taking money for things dissipates karma to some extent. So, I said, “What about $5.00?”

He said, “No. That’s just not enough.”

Then Maynard, the construction guy, said, “Okay, what about $7.50?”

So we settled on that. I didn’t want to take more money, and they were friends. I don’t like taking money for things.

When I’ve been given something, or inherited stuff, I give it away. And it’s the same with my labor. I feel that by taking money for it, I’m somehow dirtying the issue. I think that’s because of my disdain for the whole capitalist system and, maybe naïvely, I’m trying to remain apart from that. That’s why I think the art that I do makes other people see me as just not part of the normal realm. I don’t want to be thought of as different, necessarily, but I want other people to feel comfortable if they’re feeling themselves as different. There will be no shame.

So many people are into prescribed notions of what one should do, or what art should consist of. That just gets in the way. One should create beauty and be kind, be courageous.

Davis Dimock and his wife Victoria Weber passed away on 12/13/2022

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Dec 21, 2022 Jesse orr wrote:

Rest In Peace Victoria and Davis! You both were amazing people! In honor I left them a Christmas wreath, battery lit candle, woodburning portrait of them, two candy canes, bouquet of flowers and a Christmas card. I hate seeing them gone. Farewell my two amazing friends! Love you guys! Jesse orrOn Dec 16, 2022 Patrick Watters wrote:

As always, grateful…On Dec 16, 2022 Ruth wrote:

Thank you again, Richard. This conversation especially resonates.On Dec 16, 2022 abbe wrote:

What a great tribute. As i wonder more about my own choices and how I place value on my day, this interview solidifies the idea of the process of being ... connecting... creating just because. I'm privileged to even have this thought. I would have liked to meet Davis and his wife.On Dec 15, 2022 Gwen Botting wrote:

Davis was my mom's younger cousin. It always seemed that, when we visited from the Midwest, that we didn't ever have enough time to visit Davis or Uncle Marshall and Aunt Gladys. I am very grateful for this interview, as it explains a lot about my mother's family and the many differing points of view. I am deeply grateful to Davis and Victoria for living their simple, driven, honest life and sharing a little bit of it with me.On Aug 26, 2021 Arlene Holmes wrote:

I studied with a stone carver named Jose de Creeft at the art students league. He taught direct stone carving and I will never forget the lessons learned by his understanding of how a stone speaks to you. How to carve and get the essence of it. I thought of this reading about Davis in his conversation with you.On Mar 4, 2020 Sidonie wrote:

So good to relate and feel the warm glow from the heart vibrating in the whole body!!! This art-labour is undeniably beautiful in its raw and unsophisticated display, profound as it touches the soul directly and connects to the spirit. It is genuine and utterly generous. Kudos! Appreciation and gratitude for this "one of a kind" interview filled with awe... Yes, I couldn't agree more with this: "One should create beauty and be kind, be generous." Keep walking in beauty, dear Ones!On Mar 2, 2020 NANCY E Peden wrote:

Utterly beautiful though found formatting difficult.I loved the comment about hearing. I am mentoring writer and he finally got Voce to texts.! Must brag, I got it easily and I am 70.

And I feel I feel a longing as I sense here to HEAR his voice reading what he so loves.

On Mar 2, 2020 Tracey J. Jackson wrote:

You know this conversation was brought to my attention by my Son James F. Jackson of Spring Hope NC He found a kindred association with the thoughts and the way Davis looked atlife and actually has lived out and did as he wanted . I think my son has found someone who is of the same type of mind and very much the very same mind as myself and my Father and his Great Grand father on his Mother's side of his family. Nice to read of other people who approach life in such a fulfilling way. Very inspirational to read, Thanks for writing about this . and sharing with all of us. Mr. Tracey J Jackson

On Mar 1, 2020 Judy Kahn wrote:

Richard, I'd love to hear a conversation between Davis and John Whittaker, your brother and my husband, though they seem so opposite. John talked about Davis, the life he had chosen in the beautiful Vermont countryside, and of course, I wanted to go there. I wondered how the two became friends and what they might have talked about. The life Davis had chosen seemed simple, uncomplicated, even primitive, as someone notes in your interview. John, on the other hand, as a professor of religious studies, spent his days teaching or writing about the nature of god, the value and basis of religious beliefs, and all that one could say and write about the meaning of these complicated, controversial subjects. John would never have thought of his articles and books as art, but suddenly, I do. I can see how he filtered his lifetime study of logic and religious philosophy through his own belief system to create a coherent, beautiful expression of what god and religion were to him and could be to others. For me, it's a new way of discovering John, the same as this interview discovers Davis, a true artist who places rocks, plants, sticks, etc. in the landscape to create beauty and an appreciation of labor for himself and others.On Mar 1, 2020 Audace wrote:

Wish the public schools taught this ethic. Excellent interview. Couldn't stop reading it because you kept plumbing his responses.On Mar 1, 2020 Jim wrote:

Best read in 10 years, possibly 20. Maybe I should read more...Davis reminds me of so many people I never hear of these days...mainly my Father and all the People represented in my own head.

This is a Treasure.

On Mar 1, 2020 Marjorie King wrote:

His work makes my heart sing!On Mar 1, 2020 Sherry Tuegel wrote:

Humbled by this man! Now I want to visit Vermont again! <3On Mar 1, 2020 Mary Martin wrote:

Wow!! When I read about people who hear a drummer and do it.. this is really inspiring to me..I think I have mostly done what is expected or easy...On Mar 1, 2020 Patrick Watters wrote:

Delightful. The gift of friendships, wherein (who in) we find each other and our true selves too. Henri Nouwen spoke of such things often, the things of authentic life. Thank you once again for sharing some of yours. And yes, we are all artists, it is indeed permissible. }:- a.m. (anonemoose monk) aka PatrickOn Mar 1, 2020 Maureen wrote:

Wonderful. Makes me think about retiring and digging a hole and building beautiful rock cairns in my yard.On Mar 1, 2020 Ruth Goodman wrote:

💘 love this!😊On Dec 17, 2019 Wes Rumble wrote:

Fantastic picture of Davis’ being. Thanks,Richard.