Transforming Trauma Into Creative Energy

Instead of giving in, the deepest thing we can do with trauma is to transmute pain into actions that heal ourselves and help other people. A powerful meditation on love, loss, recovery and resistance.

In 1998 my wife Shoshana was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. An accomplished artist and psychotherapist who worked with Holocaust survivors (of whom she was one), the woman who once spoke eight languages could barely speak at all.

Did Shoshana know who I was? There were good days and bad. During the bad days I would say that the ‘light was definitely out.’ On the good days, I would come to her and embrace her. I would kiss her, and she would kiss me back, which elicited wonderful memories of a loving marriage.

Shoshana died in 2012, but during our half century together, she taught me that trauma can be an opening for transformation through the way she dealt with her own experiences, in her psychotherapeutic work, and through my own role as her care giver later in life.

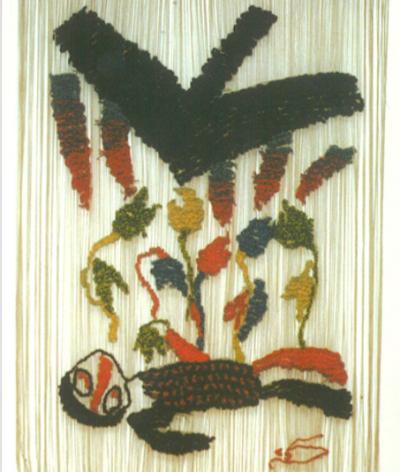

“War.” Tapestry by Shoshana Comet. Credit: Ted Comet. All rights reserved.

***

On the morning after Hitler’s invasion of Belgium in 1940, Shoshana Ungar and her family fled the city of Antwerp and crossed the border into France. They knew what was coming: the persecution of Jewish residents, followed, as the world learned later, by a train journey into the extermination camps of the Holocaust.

Leaving everything they owned behind them, the Ungars crisscrossed the countryside of France by train and on foot, hiding out at night and surviving multiple attacks from the sky by German aircraft. Eventually they reached neutral Portugal via Northern Spain, where an American consular official in Porto gave them visas to enter the USA.

The family arrived in New York in 1941, and I met Shoshana ten years later. We were married in 1952. As to the trauma of her escape, she kept that hidden deep inside. It was not until years later that she was able to tell her story through her art.

One day in 1968, Shoshana announced that she had joined a course on weaving. When I asked her why she chose weaving over painting, she told me that “paint which derives from chemicals is inert, and a painting when completed is fixed in time; whereas with wool, which comes from a living animal, there continues to be movement and change, as with life itself.”

Shoshana soon left the course because it was geared to making crafts instead of art. So we bought a loom which she worked on at home. Basically she was self-taught. She wove five 6-foot high tapestries which served as a means to unshackle herself from her holocaust trauma.

While working on a tapestry called “War,” her right arm became paralyzed. Doctors could find no physical cause for the problem, so she entered psychotherapy. She discovered that her weaving was surfacing memories that were so painful that she sub-consciously self-paralyzed her arm in order to prevent herself from continuing.

Once these memories had been worked out in therapy, her arm regained its use. She also lost her fear of flying. Having seen German Stukas strafing train passengers on her train journeys through France in 1940, an airplane to Shoshana was not a vehicle of transportation - it was an instrument of death.

After completing her fifth tapestry, the “Affirmation of Life,” Shoshana closed her loom, and never opened it again. Instead, she trained to become a psychotherapist herself, working with Holocaust survivors and their families who had been scarred by their experience.

When I asked her why she gave up her art she said: “I’m not. Being a good therapist is more an art than a science. My kind of weaving is as emotionally demanding as providing psychotherapy. I cannot do both. And it is more important to me to save the quality of life of others than just to express my own pain in weaving.”

Shoshana's psychotherapeutic work rejected the conventional wisdom of the time. She challenged the model of “Survivors’ Syndrome” that was popular in psychoanalysis, which focused exclusively on survivors as victims who were defined by their guilt, anxiety and depression.

Instead, she advocated a more positive approach, recognizing the dignity and agency of those who had found the inner strength to survive their experiences and build new lives for themselves.

“We have focused on the suffering of survivors,” she told the World Council of Jewish Communal Service Quadrennial Meeting in Jerusalem in 1988, “but in that process we have lost sight of the moral and spiritual resistance that enabled them to survive, and to form new relationships.”

Moving away from the stigma of victimhood was, she argued, the key to transforming the experience of trauma into a positive pathway for self-healing, and service to others. By focusing on people’s strengths instead of their vulnerabilities, they could become active agents of their own transformation, and offer their support to those around them who were faced with similar traumas. They were not to be seen as passive, or as a ‘burden’ on their families.

Shoshana discovered how to convert her own trauma into some creative act of energy, first through her weaving and then in her practice as a psychotherapist. In this process, she helped to alter the ways in which Holocaust survivors were perceived and supported.

***

Even after her diagnosis for Alzheimer’s, Shoshana continued to teach me about trauma and transformation - in this case mine - since the principles were the same: instead of giving in, the deepest thing we can do with trauma is to transmute pain into creative action that helps ourselves and other people.

By this time my wife could not do anything for herself. She had to be cared for in every way. But I wanted her at home. I didn’t want to put her into an institution.

No matter how much empathy people have, they can’t truly grasp the horror of losing your loved one bit by bit, day by day. I lost a very, very big piece of myself. There’s no way of overcoming the depth of that loss, because what you have is the death of your marriage, but a death that can’t be mourned. There was no closure so long as Shoshana was still alive. It was like an open wound which I knew was only going to get worse.

When somebody dies that you love, you try to work it through and then move on to the next phase of your life. But as long as your partner is still physically alive, you can’t mourn or move on in that way. It’s the death of a partnership, and you can’t really integrate it, internalize it and move on. It’s always there. The woman I married, who was my life partner, with whom I shared everything, was no longer there.

I did go through a period of anger, of course. I remember once feeling so down. I was walking down the street and I looked heavenward and said "God, take us both. Just do it gently." I really didn’t want to live. But then I found that the degree of resilience people have - Shoshana, myself and others - is quite stunning.

So I joined an Alzheimer’s support group in New York. I’m able to support the newcomers because I’ve been there before, and I’ve been through every stage that they’re going through and will go through, so I'm able to be helpful to others and they are helpful to me. But as my wife taught me through her own experiences of trauma and recovery, the idea of helping someone else to heal is very much a self-healing process. There’s no question about it. The idea of using your pain for some constructive purpose is actualized when you help someone else.

When newcomers come to the group and ask “how am I going to find the strength to handle this situation,” I tell them to use the following analogy. “You’re doing weightlifting”, I say, “and you can only start with a light weight until you buildup to something heavier. You could never do in the beginning what you can do at the end.” The same thing happens with what I call our ‘psychic musculature.’

The trauma of Alzheimer’s can help us to find and develop the inner strength to deal with the situation. It’s the same lesson that Shoshana taught about survivors of the Holocaust.

I’ll leave the last words to my wife, in her Jerusalem speech of 1988:

“The biggest challenge everyone faces is how we handle trauma, for everyone suffers trauma in one form or another. And the advice we are usually given is ‘to put it behind us and move on.’”

Shoshana claimed that there was something more profound that can be done, and that is to “use the trauma and transmute it into creative energy and action.”

She did that twice, through her art and then her therapy practice. “Those who achieve this,” she said, “are moral and spiritual victors.”

Ted Comet is Honorary Associate Executive Vice President of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, which is engaged in rescue, relief and reconstruction activities in over 70 countries worldwide. He was born in Cleveland and now lives in New York City. Ted has received numerous awards for his work during a lifetime of community service.

SHARE YOUR REFLECTION

3 Past Reflections

On Jun 15, 2014 Symin wrote:

Thank you, Mr. Comet, for sharing this story. It's a gift to victims of all sorts of unspeakable events for it illustrates how pain is intensified by failing to work through it. Finding a way to serve others is perhaps the best and only way to serve yourself.

On Jun 15, 2014 Mamta Nanda wrote:

Thank you for this beautiful sharing.It is not easy to be with someone you love who is suffering, and is withering away gradually. I found the book - Gift of Alzheimer's - very helpful when my mother was suffering from dementia in the last few months of her life. With time, I am able to see the gift from her suffering.

2 replies: Carl, Jarita | Post Your Reply

On Jun 16, 2014 Kristin Pedemonti wrote:

Thank you Mr Comet for a beautifully shared tribute to your wife, her work and to transmuting trauma to creativity and serving others. As a Cause Focused Storyteller, I work with many different populations worldwide, serving as a catalyst for people to share their stories whether verbally or in print. It's been healing to my own challenges in life as well. May your wife's legacy live on through all the lives she touched and may yours as well as you have guided others through the journey. Hugs from my heart to yours, Kristin

Post Your Reply