Profit vs. Principle: The Neurobiology of Integrity

Let your better self rest assured: Dearly held values truly are sacred, and not merely cost-benefit analyses masquerading as nobel intent, concludes a new study on the neurobiology of moral decision-making. Such values are conceived differently, and occur in very different parts of the brain, than utilitarian decisions.

Let your better self rest assured: Dearly held values truly are sacred, and not merely cost-benefit analyses masquerading as nobel intent, concludes a new study on the neurobiology of moral decision-making. Such values are conceived differently, and occur in very different parts of the brain, than utilitarian decisions.

“Why do people do what they do?” said neuroscientist Greg Berns of Emory University. “Asked if they’d kill an innocent human being, most people would say no, but there can be two very different ways of coming to that answer. You could say it would hurt their family, that it would be bad because of the consequences. Or you could take the Ten Commandments view: You just don’t do it. It’s not even a question of going beyond.”

In a study published Jan. 23 in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, Berns and colleagues posed a series of value-based statements to 27 women and 16 men while using an fMRI machine to map their mental activity (Left: Blood flows to different parts of the brain in utilitarian (green) and matter-of-principle (yellow) decisions. Image: Berns et al./Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B.) The statements were not necessarily religious, but intended to cover a spectrum of values ranging from frivolous (“You enjoy all colors of M&Ms”) to ostensibly inviolate (“You think it is okay to sell a child”).

After answering, test participants were asked if they’d sign a document stating the opposite of their belief in exchange for a chance at winning up to $100 in cash. If so, they could keep both the money and the document; only their consciences would know.

According to Berns, this methodology was key. The conflict between utilitarian and duty-based moral motivations is a classic philosophical theme, with historical roots in the formulations of Jeremy Bentham and Immanuel Kant, and other researchers have studied it — but none, said Berns, had combined both brain imaging and a situation where moral compromise was realistically possible.

“Hypothetical vignettes are presented to people, and they’re asked, ‘How did you arrive at a decision?’ But it’s impossible to really know in a laboratory setting,” said Berns. “Signing your name to something for a price is meaningful. It’s getting into integrity. Even at $100, most all our test subjects put some things into categories they were willing to take money for, and others they wouldn’t.”

When test subjects agreed to sell out, their brains displayed common signatures of activity in regions previously linked to calculating utility. When they refused, activity was concentrated in other parts of their brains: the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, which is known to be involved in processing and understanding abstract rules, and the right temporoparietal junction, which has been implicated in moral judgement.

'If it's a sacred value to you, then you can't even conceive of it in a cost-benefit framework.'

In short, when people didn’t sell out their principles, it wasn’t because the price wasn’t right. It just seemed wrong. “There’s one bucket of things that are utilitarian, and another bucket of categorical things,” Berns said. “If it’s a sacred value to you, then you can’t even conceive of it in a cost-benefit framework.”

According to Berns, the implications could help people better understand the motivations of others. He’s now studying how moral equations change according to the social popularity of values, and what happens in the brain when deep-seated principles are confronted with reasoned arguments. “Can I change your mind? Lessen your conviction? Strengthen it? And how does this happen? Is this appealing to rule-based networks, or to systems of reward and loss?” Berns wondered.

Whether sacred principles offer utilitarian benefits over long periods of time — many years, perhaps many generations, and at population-wide as well as individual scales — is beyond the current study design, but Berns suspects that one of their benefits is simplicity.

“My hypothesis about the Ten Commandments is that they exist because they’re too hard to think about on a cost-benefit basis,” he said. “It’s far easier to have a rule saying, ‘Thou shalt not commit adultery.’ It simplifies decisionmaking.”

Citation: “The price of your soul: neural evidence for the non-utilitarian representation of sacred values.” By Gregory S. Berns, Emily Bell, C. Monica Capra, Michael J. Prietula, Sara Moore, Brittany Anderson, Jeremy Ginges and Scott Atran. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, Vol. 367 No. 1589, March 5, 2012.

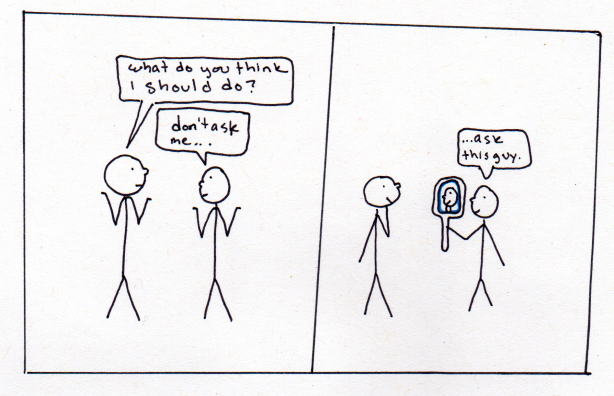

This article was reprinted with permission, and originally appeared in WIRED Magazine. Brandon Keim is a freelance science journalist whose blog is at earthlab.net and is on Twitter as @9Brandon. Comic above reprinted with permission from DharmaComics.com

SHARE YOUR REFLECTION

5 Past Reflections

On Mar 1, 2012 Cgatere wrote:

My view is that the Bible has the answer a,science will work very hard to confirm,why not take the shortcut "study the Bible"

Gatere c

On Feb 29, 2012 Noor A.F wrote:

thank you. break it down so that we understand it better. I mean I would like more on neuro.

On Feb 29, 2012 Sam wrote:

Very interesting indeed... I think it's wonderful that neuroscience is looking into this kind of thing!

1 reply: Just | Post Your Reply

On Feb 29, 2012 Mark wrote:

The fascinating aspect of this work is that if our non-utilitarian values are shaped by our upbringing as much as much as natural law, that inter-cultural conflict may be be more difficult to resolve than one would hope. For example, this might help us appreciate the difficulty in helping children who have grown up in a war environment to accept their parents' enemies as possible friends and respected colleagues. Thank you for bringing this research to our attention.

1 reply: Hunygun | Post Your Reply

On Oct 29, 2012 Dianne wrote:

The neuro decision evidences itself in body language and facial expression (often a micro levels we may not realize we see and interpret) thus the "truth" is never hidden in the recesses of the mind.

Post Your Reply