How to Find Your Purpose and Do What You Love

Why prestige is the enemy of passion, or how to master the balance of setting boundaries and making friends.

“Find something more important than you are,” philosopher Dan Dennett once said in discussing the secret of happiness,“and dedicate your life to it.” But how, exactly, do we find that? Surely, it isn’t by luck. I myself am a firm believer in the power of curiosity and choice as the engine of fulfillment, but precisely how you arrive at your true calling is an intricate and highly individual dance of discovery. Still, there are certain factors — certain choices — that make it easier. Gathered here are insights from seven thinkers who have contemplated the art-science of making your life’s calling a living.

“Find something more important than you are,” philosopher Dan Dennett once said in discussing the secret of happiness,“and dedicate your life to it.” But how, exactly, do we find that? Surely, it isn’t by luck. I myself am a firm believer in the power of curiosity and choice as the engine of fulfillment, but precisely how you arrive at your true calling is an intricate and highly individual dance of discovery. Still, there are certain factors — certain choices — that make it easier. Gathered here are insights from seven thinkers who have contemplated the art-science of making your life’s calling a living.

PAUL GRAHAM ON HOW TO DO WHAT YOU LOVE

PAUL GRAHAM ON HOW TO DO WHAT YOU LOVE

Every few months, I rediscover and redevour Y-Combinator founder Paul Graham’s fantastic 2006 article, How to Do What You Love. It’s brilliant in its entirety, but the part I find of especial importance and urgency is his meditation on social validation and the false merit metric of “prestige”:

What you should not do, I think, is worry about the opinion of anyone beyond your friends. You shouldn’t worry about prestige. Prestige is the opinion of the rest of the world.

[…]

Prestige is like a powerful magnet that warps even your beliefs about what you enjoy. It causes you to work not on what you like, but what you’d like to like.

[…]

Prestige is just fossilized inspiration. If you do anything well enough, you’ll make it prestigious. Plenty of things we now consider prestigious were anything but at first. Jazz comes to mind—though almost any established art form would do. So just do what you like, and let prestige take care of itself.

Prestige is especially dangerous to the ambitious. If you want to make ambitious people waste their time on errands, the way to do it is to bait the hook with prestige. That’s the recipe for getting people to give talks, write forewords, serve on committees, be department heads, and so on. It might be a good rule simply to avoid any prestigious task. If it didn’t suck, they wouldn’t have had to make it prestigious.”

More of Graham’s wisdom on how to find meaning and make wealth can be found in Hackers & Painters: Big Ideas from the Computer Age.

ALAIN DE BOTTON ON SUCCESS

ALAIN DE BOTTON ON SUCCESS

Alain de Botton, modern philosopher and creator of the“literary self-help genre”, is a keen observer of the paradoxes and delusions of our cultural conceits.

Alain de Botton, modern philosopher and creator of the“literary self-help genre”, is a keen observer of the paradoxes and delusions of our cultural conceits.

In The Pleasures and Sorrows of Work, he takes his singular lens of wit and wisdom to the modern workplace and the ideological fallacies of “success.”

His terrific 2009 TED talk offers a taste:

One of the interesting things about success is that we think we know what it means. A lot of the time our ideas about what it would mean to live successfully are not our own. They’re sucked in from other people. And we also suck in messages from everything from the television to advertising to marketing, etcetera. These are hugely powerful forces that define what we want and how we view ourselves. What I want to argue for is not that we should give up on our ideas of success, but that we should make sure that they are our own. We should focus in on our ideas and make sure that we own them, that we’re truly the authors of our own ambitions. Because it’s bad enough not getting what you want, but it’s even worse to have an idea of what it is you want and find out at the end of the journey that it isn’t, in fact, what you wanted all along.”

HUGH MACLEOD ON SETTING BOUNDARIES

HUGH MACLEOD ON SETTING BOUNDARIES

Cartoonist Hugh MacLeod is as well-known for his irreverent doodles as he is for his opinionated musings on creativity, culture, and the meaning of life. In Ignore Everybody: and 39 Other Keys to Creativity, he gathers his most astute advice on the creative life. Particularly resonant with my own beliefs about the importance of choices is this insight about setting boundaries:

Cartoonist Hugh MacLeod is as well-known for his irreverent doodles as he is for his opinionated musings on creativity, culture, and the meaning of life. In Ignore Everybody: and 39 Other Keys to Creativity, he gathers his most astute advice on the creative life. Particularly resonant with my own beliefs about the importance of choices is this insight about setting boundaries:

16. The most important thing a creative person can learn professionally is where to draw the red line that separates what you are willing to do, and what you are not.

Art suffers the moment other people start paying for it. The more you need the money, the more people will tell you what to do. The less control you will have. The more bullshit you will have to swallow. The less joy it will bring. Know this and plan accordingly.”

Later, MacLeod echoes Graham’s point about prestige above:

28. The best way to get approval is not to need it.

This is equally true in art and business. And love. And sex. And just about everything else worth having.”

LEWIS HYDE ON WORK VS. LABOR

LEWIS HYDE ON WORK VS. LABOR

After last year’s omnibus of 5 timeless books on fear and the creative process, a number of readers rightfully suggested an addition: Lewis Hyde’s 1979 classic, The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World, of which David Foster Wallace famously said, “No one who is invested in any kind of art can read The Gift and remain unchanged.”

After last year’s omnibus of 5 timeless books on fear and the creative process, a number of readers rightfully suggested an addition: Lewis Hyde’s 1979 classic, The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World, of which David Foster Wallace famously said, “No one who is invested in any kind of art can read The Gift and remain unchanged.”

In this excerpt, originally featured here in January, Hyde articulates the essential difference between work and creative labor, understanding which takes us a little closer to the holy grail of vocational fulfillment:

Work is what we do by the hour. It begins and, if possible, we do it for money. Welding car bodies on an assembly line is work; washing dishes, computing taxes, walking the rounds in a psychiatric ward, picking asparagus — these are work. Labor, on the other hand, sets its own pace. We may get paid for it, but it’s harder to quantify… Writing a poem, raising a child, developing a new calculus, resolving a neurosis, invention in all forms — these are labors.

Work is an intended activity that is accomplished through the will. A labor can be intended but only to the extent of doing the groundwork, or of not doing things that would clearly prevent the labor. Beyond that, labor has its own schedule.

…

There is no technology, no time-saving device that can alter the rhythms of creative labor. When the worth of labor is expressed in terms of exchange value, therefore, creativity is automatically devalued every time there is an advance in the technology of work.”

Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi has a term for the quality that sets labor apart from work: flow — a kind of intense focus and crisp sense of clarity where you forget yourself, lose track of time, and feel like you’re part of something larger. If you’ve ever pulled an all-nighter for a pet project, or even spent 20 consecutive hours composing a love letter, you’ve experienced flow and you know creative labor.

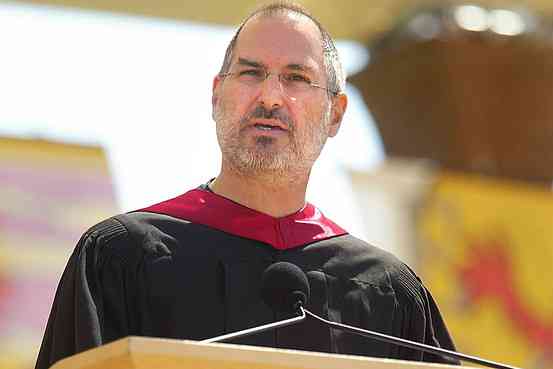

STEVE JOBS ON NOT SETTLING

STEVE JOBS ON NOT SETTLING

In his now-legendary 2005 Stanford commencement address, an absolute treasure in its entirety, Steve Jobs makes an eloquent case for not settling in the quest for finding your calling — a case that rests largely on his insistence upon the power of intuition:

Your work is going to fill a large part of your life, and the only way to be truly satisfied is to do what you believe is great work. And the only way to do great work is to love what you do. If you haven’t found it yet, keep looking. Don’t settle. As with all matters of the heart, you’ll know when you find it. And, like any great relationship, it just gets better and better as the years roll on. So keep looking until you find it. Don’t settle.”

ROBERT KRULWICH ON FRIENDS

ROBERT KRULWICH ON FRIENDS

Robert Krulwich, co-producer of WNYC’s fantastic Radiolab, author of the ever-illuminating Krulwich Wonders and winner of a Peabody Award for broadcast excellence, is one of the finest journalists working today. In another great commencement address, he articulates the infinitely important social aspect of loving what you do — a kind of social connectedness far more meaningful and genuine than those notions of prestige and peer validation.

You will build a body of work, but you will also build a body of affection, with the people you’ve helped who’ve helped you back. This is the era of Friends in Low Places. The ones you meet now, who will notice you, challenge you, work with you, and watch your back. Maybe they will be your strength.

…

If you can… fall in love, with the work, with people you work with, with your dreams and their dreams. Whatever it was that got you to this school, don’t let it go. Whatever kept you here, don’t let that go. Believe in your friends. Believe that what you and your friends have to say… that the way you’re saying it — is something new in the world.”

THE HOLSTEE MANIFESTO

THE HOLSTEE MANIFESTO

You might recall The Holstee Manifesto as one of our 5 favorite manifestos for the creative life, an eloquent and beautifully written love letter to the life of purpose. (So beloved is the manifesto around here that it has earned itself a permanent spot in the Brain Pickings sidebar, a daily reminder to both myself and you, dear reader, of what matters most.)

This is your life. Do what you love, and do it often. If you don’t like something, change it. If you don’t like your job, quit. If you don’t have enough time, stop watching TV. If you are looking for the love of your life, stop; they will be waiting for you when you start doing things you love.”

The Holstee Manifesto is now available as a beautiful letterpress print, a 5×7greeting card printed on handmade paper derived from 50% elephant poo and 50% recycled paper, and even a baby bib — because it’s never too early to instill the values of living from passion.

This article is reprinted with permission from Maria Popova. She is a cultural curator and curious mind at large, who also writes for Wired UK, The Atlantic and Design Observer, and is the founder and editor in chief of Brain Pickings (which offers a free weekly newsletter). More from Maria on DailyGood: 7 Must-Read Books on Education 7 Ways to Have More by Owning Less Where Children Sleep: A Poignant Photo Series The Neuropsychology of "Don't Worry, Be Happy"

SHARE YOUR REFLECTION

8 Past Reflections

On Jun 2, 2012 Death Quotes wrote:

This is an excellent post. I liked this post very much. All

things are described in very excellent way. In my eyes you should keep on such

kind of postings for us. In future I would like to come here again for some new

and more information.

On Apr 24, 2012 Jconsidine wrote:

I still see the yellow quote marks in the background. It is distracting from the message.

On Apr 23, 2012 Sundisilver wrote:

Great article. Thanks so much.

I have to agree with Ruth's comment about the bright and big yellow quote marks as background for some wonderful quotes. It makes it hard to read. And the text /quotes are soooo worth reading.

On Apr 22, 2012 Ruth Schwartz wrote:

Thanks so much for posting this and I am having a really hard time reading the words over those big yellow quote marks. Hope someone will change this soon. Thanks!

On Apr 22, 2012 noor a.f wrote:

On Apr 22, 2012 Cherie Dirksen wrote:

Great article, thanks. I especially agree with setting boundaries and not worrying about what other people think. It is a hard obstacle to overcome but it is a vital one. You are not always going to have universal popularity with what you do, but if you love what you do, it doesn't matter. For anyone who wants to download a free copy of 'Creative Expression - How to find your inspiration...' (a PDF with inspirational teachings about finding your purpose accompanied with art) please visit: http://wordpress.us2.list-m...

On Aug 22, 2021 Anna Tasya Cindy Wika wrote:

Pemberian nama lokasi tempat yang benar-benar kuat hubunganya dengan kejadian, figur, atau benda lainnya yang dipandang sakral, legenda, atau karena wujud sebuah situs. Begitu juga bernama Sumur Tiga.

Jaman dulu disekitar pantai ada tiga buah sumur sebagai mata air untuk masyarakat seputar. Benar-benar luar dapat, https://piknikholic.com/ karena air yang dibuat bukan air asin but air tawar.

Tetapi, sayang sekarang ini sumur itu tidak dipakai kembali oleh masyarakat seputar, tapi jadi saksi sejarah akan masa akhirnya yang besar hati.

Post Your Reply