Arianna Huffington:Can Gratitude Help You Thrive

In an excerpt from her new book, Arianna Huffington explores how gratitude helped her to find meaning in pain and loss.

I’ve come to believe that living in a state of gratitude is the gateway to grace.

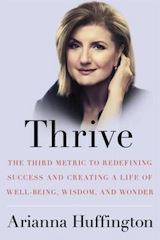

This essay was adapted from Arianna Huffington's new book Thrive: The Third Metric to Redefining Success and Creating a Life of Well-Being, Wisdom, and Wonder.

Grace and gratitude have the same Latin root, gratus. Whenever we find ourselves in a stop-the-world-I-want-to-get-off mindset, we can remember that there is another way and open ourselves to grace. And it often starts with taking a moment to be grateful for this day, for being alive, for anything.

The Oxford clinical psychologist Mark Williams suggests the “ten finger gratitude exercise,” in which once a day you list ten things you’re grateful for and count them out on your fingers. Sometimes it won’t be easy. But that’s the point—“intentionally bringing into awareness the tiny, previously unnoticed elements of the day.”

Gratitude exercises have been proven to have tangible benefits. According to a study by researchers from the University of Minnesota and the University of Florida, having participants write down a list of positive events at the close of a day—and why the events made them happy—lowered their self-reported stress levels and gave them a greater sense of calm at night.

I find that I’m not only grateful for all the blessings in my life, I’m also grateful for all that hasn’t happened—for all those close shaves with “disaster” of some kind or another, all the bad things that almost happened but didn’t. The distance between them happening and not happening is grace.

And then there are the disasters that did happen, that leave us broken and in pain.

For me, such a moment was losing my first baby. I was thirty-six and ecstatic at the prospect of becoming a mother. But night after night, I had restless dreams. Night after night I could see that the baby—a boy—was growing within me, but his eyes would not open. Days became weeks, and weeks turned into months. Early one morning, barely awake myself, I asked out loud, “Why won’t they open?” I knew then what was only later confirmed by the doctors. The baby’s eyes were not meant to open; he died in my womb before he was born.

Women know that we do not carry our unborn babies only in our wombs. We carry them in our dreams and in our souls and in our every cell. Losing a baby brings up so many unspoken fears: Will I ever be able to carry a baby to term? Will I ever be able to become a mother? Everything felt broken inside. As I lay awake during the many sleepless nights that followed, I began to sift through the shards and splinters, hoping to find reasons for my baby’s stillbirth.

Staggering through a minefield of hard questions and partial answers, I began to make my way toward healing. Dreams of my baby gradually faded, but for a time it seemed as if the grief itself would never lift. My mother had once given me a quotation from Aeschylus that spoke directly to these hours: “And even in our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart, and in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom to us by the awful grace of God.” At some point, I accepted the pain falling drop by drop and prayed for the wisdom to come.

I had known pain before. Relationships had broken, illnesses had come, death had taken people I loved. But I had never known a pain like this. What I learned through it is that we are not on this earth to accumulate victories, or trophies, or experiences, or even to avoid failures, but to be whittled and sandpapered down until what’s left is who we truly are. This is the only way we can find purpose in pain and loss, and the only way to keep returning to gratitude and grace.

I love saying grace—even silently—before meals and when I travel around the world, observing different traditions. When I was in Tokyo in 2013 for the launch of HuffPost Japan I loved learning to say itadakimasu before every meal. It simply means “I receive.” When I was in Dharamsala, India, every meal started with a simple prayer.

Growing up in Greece, I was used to a simple blessing before each meal, sometimes a silent one, even though I wasn’t brought up in a particularly religious household. “Grace isn’t something that you go for, as much as it’s something you allow,” wrote John-Roger, the founder of the Movement of Spiritual Inner Awareness. “However you may not know grace is present, because you have conditioned the way you want it to come, for example, like thunder or lightning, with all the drama, rumbling, and pretense of that. In fact, grace comes in very naturally, like breathing.”

The GGSC's coverage of gratitude is sponsored by the John Templeton Foundation as part of our Expanding Gratitude project.

Both monks and scientists have affirmed the importance of gratitude in our lives. “It is a glorious destiny to be a member of the human race,” wrote Thomas Merton, a Trappist monk from Kentucky, “though it is a race dedicated to many absurdities and one which makes many terrible mistakes: yet, with all that, God Himself gloried in becoming a member of the human race. A member of the human race! To think that such a commonplace realization should suddenly seem like news that one holds the winning ticket in a cosmic sweepstake.”

What the foremost researchers in the field of gratitude,Robert Emmons of the University of California, Davis, andMichael McCullough of the University of Miami, have established is that “a life oriented around gratefulness is the panacea for insatiable yearnings and life’s ills… At the cornerstone of gratitude is the notion of undeserved merit. The grateful person recognizes that he or she did nothing to deserve the gift or benefit; it was freely bestowed.” Gratitude works its magic by serving as an antidote to negative emotions. It’s like white blood cells for the soul, protecting us from cynicism, entitlement, anger, and resignation.

It’s summed up in a quote I love, attributed to Imam Al- Shafi’i, an eighth-century Muslim jurist: “My heart is at ease knowing that what was meant for me will never miss me, and that what misses me was never meant for me.”

This article is printed here with permission from the Greater Good Science Center (GGSC). You can learn more about the science and power of gratitude at the Greater Good Gratitude Summit.

SHARE YOUR REFLECTION

2 Past Reflections

On Jun 7, 2014 Stan wrote:

The quoted experts say, "...At the cornerstone of gratitude is the notion of undeserved merit." That struck me. Is that true? What is actually meant by "undeserved"? I think that a sense that good things don't come exclusively through our efforts is intrinsic. I think I can have a sense of gratitude for my successes in life without thinking that I did nothing to create them. I think it's unhealthy to believe I'm unworthy of them. We often equate "undeserved" with "unworthy." We have all been told we are miserable sinners who don't deserve salvation, that we are so flawed when we are born that we only deserve eternal torture in a lake of fire, and that we are saved only by grace and not because of anything we do ourselves.

I think it is possible to have a sense of gratitude for good things in our life while believing that we had some role in them happening. "God helps those who help themselves. Pray to God, but row away from the rocks."

On Jun 7, 2014 Kristin Pedemonti wrote:

Wonderful Share on Gratitude. What I enjoyed the most was "What I learned through it is that we are not on this earth to accumulate victories, or trophies, or experiences, or even to avoid failures, but to be whittled and sandpapered down until what’s left is who we truly are." Living in Gratitude reframes and helps us move forward and onward. Hugs from my heart to yours!

Post Your Reply