Kentaro Toyama: Beyond Technological Utopianism

After 12 years at Microsoft, 5 of which were spent in India, applying electronic technologies for international development, Kentaro Toyama came to one conclusion: technology is not the answer.

In our digital age of exponential tech innovation—where the average American adult spends 11 hours a day on electronic media, the majority of the nation’s cell phone owners sleep with it by their side, and companies like Google and Levis are coming up with ‘smart jeans’— the undercurrents of mainstream culture seem to be marching to the beat of a drum far different from Kentaro’s—one that toots technology as an indefatigable sign of progress.

Of course, Kentaro agrees there are benefits to innovation. “Technology is terrific, and it’s helped the rich world come far,” he admits. “But in the end, there’s no real progress without change in people."

Much like Tom Mahon’s question, “Have we become the tools of our tools?” may invite one to push on the breaks and reflect on the signs of our times, Kentaro Toyama’s Awakin Call last week offered enriching insights on the progress that lies beyond technological utopianism.

Insights from International Development

In 2005, Kentaro found himself in Bangalore, India. He was spearheading Microsoft Research India—a lab focused on leveraging technology for socioeconomic development in poor communities.

“We used PCs, mobile phones, and custom hardware to support efforts in agriculture, education, micro-finance, healthcare, governance, and so on,” he describes. “If not that technology was going to change everything in dramatic ways, at least it would be able to help in a variety of situations.”

Yet, what he found after 5+ years in 50-odd research projects and a team of 10 researchers— half of whom were technologists and the other half social scientists— was that it mattered who they worked with, not how good the technologies they used were.

“If our partners were very committed to their missions, and good at what they did, then they would use the technology that we designed in a positive way to enhance what they were already doing,” he elaborates. “On the other hand, if our partners were not particularly committed to their missions or not capable of executing their missions, then it didn't make a difference. No matter how good the technology was, it didn't help.”

In one particular instance, Kentaro was visiting an education project just outside Bangalore. They had provided teachers with a tool that allows teachers to easily screen visual materials on a projector, free of prep-work like PowerPoint slides.

“But when I went to visit this school, what I found was that when the class started, for the first few minutes, the teacher was not able to get the projector to work. So he started twiddling around, and then eventually, I jumped in to help.”

By the time they rebooted the laptop, got everything working, and all the students back in their seats, twenty the forty-five minute class had already gone by.

“No matter how good the technology was, without the larger system support of IT system as well as adequate training to use the technology and beyond, it just didn’t make a difference. In fact, it probably caused some harm.”

Again and again, this happened in various cases.

“Basically, it wasn’t the technology doing the magic,” Kentaro realized. “Whenever technology did something good, it was human beings doing the right thing and using technology as the tool to amplify what they were doing. So I came to the conclusion that technology amplifies underlying human forces, and it doesn't fix broken systems, or broken institutions.”

Technology and Consciousness Development

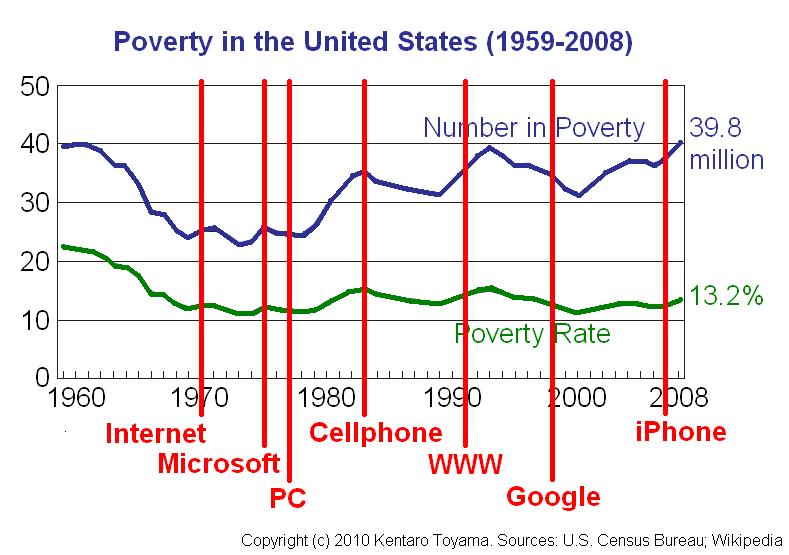

The last four decades in the US has given rise to an “explosion of digital innovation.”

“Everything from the Internet to cell phones, to Facebook, to Google, to Microsoft, and to whatever digital technology that we think as being incredibly helpful has happened in the last four decades,” Kentaro points out.

Yet during that same span of time, the United States has not seen poverty decline, and in fact, it has gone up since the recession.

The description of his just-released book Geek Heresy: Rescuing Social Change from the Cult of Technology, adds:

“Computers in Bangalore are locked away in dusty cabinets because teachers don’t know what to do with them. Mobile phone apps meant to spread hygiene practices in Africa fail to improve health. Executives in Silicon Valley evangelize novel technologies at work even as they send their children to Waldorf schools that ban electronics… Why then do we keep hoping that technology will solve our greatest social ills?”

“If you believe that technology by itself, is somehow causing positive social changes, these facts just fly in the face of that idea,” the information technology professor states.

If we want to actually create such changes, we must look at the intent behind the tech—the people and motivations within them that draw us to innovate in the first place.

Heart, Mind, and Will

In Part II of his book, Kentaro offers three building blocks of all human virtues: heart, mind, and will—which can be described as “good intention, good judgment, and good self-control.”

When those three elements are present in good form, the researcher explains, then technology can in fact be used in a positive way, and with good outcomes.

“But if they are not in place, then there is no technology that will fix the situation. They are the deeply social challenges that we have to address.”

But how exactly does one develop these virtues?

While Kentaro feels that we as a human civilization don’t have a well-rounded model for how that happens, he offers ideas from his own personal experiences.

“I think we develop virtues indirectly, as we chase our own aspirations… I was a pretty lazy kid who just barely did enough work to get by in school, but because I wanted to be good at things and to be recognized for being good at things, I worked hard in college to do the things that I wanted. So in some sense, I’ve learned the self-control in order to achieve aspirations that I had as a teenager, as a young man.”

He cites an example from when he was in high school:

"When I was 15, I entered a high school physics egg-drop contest in which we were supposed to design the lightest container that would allow an egg to survive a drop from a water tower. I won, but was disappointed that the victory wasn't trumpeted in the next morning's school-wide announcements. That led me to introspect, and I found that:

1) I was unconsciously seeking public accolades for my ingenuity;

2) I felt immature doing so; yet

3) I couldn't think myself out of the desire.

I see that moment as the beginning of my conscious adulthood, as well as the defining crux of my life. It has been with me ever since, despite having tried a lot of things to grow beyond it. The only way to let it go, it seems to me now, is a single-minded pursuit of the aspiration until I'm exhausted of it."

While we can’t will ourselves out of our demons, as we pursue them, we come to realize that those empty pursuits don’t make us any happier than we would be without them.

“Over time, the chasing of the aspiration have kind of eroded the desire. I see myself being less interested in public recognition in a funny way, because I have chased it. So more and more, I have mental slack to chase other [virtuous] aspirations that have always been with me, but would never be as loud as the one for recognition.”

For example, as he achieved and eroded his desire for recognition, Kentaro noticed that the desire to make an impact on the world that is positive for other people, and to help others achieve their own aspiration, grew louder and more clear.

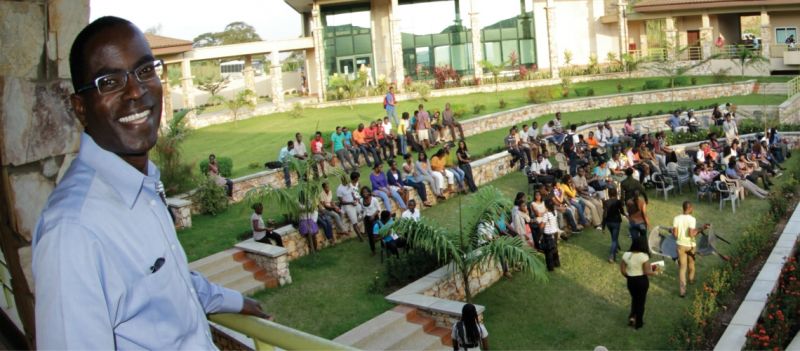

A similar example happened with his coworker at Microsoft, Patrick Awuah, who was born and raised in Ghana, and had moved to the US after receiving a scholarship to attend Swarthmore University.

“His early ambitions were relatively modest,” Kentaro describes. “Exactly the kind we all have. He wanted to have a good job. He was interested in engineering, so he wanted to have intellectual contributions in the technology sector. He joined Microsoft, and he happened to join exactly at the time when Microsoft was rapidly growing. So he did very well.”

Then, after 10 years, he looked back and realized he achieved all that he had set out to do. He could run an organization and manage lots of people, but it didn’t engage him in the same way anymore.

“I had a conversation with him once. He said it just didn’t seem that important to figure out what button should go where on an operative UI.” Kentaro recalls. “Until that moment, that was his primary occupation.”

So eventually, Patrick left Microsoft, went to business school to gain knowledge to start a university in Ghana. In 2002, Ashesi University was founded. Kentaro taught there the first year. Today, they have 400 students at any given point, and many of the early students have graduated and gone on to start their own nonprofit organizations.

“What’s interesting about all this,” Kentaro concludes, “was that it all comes down to some transformative change that happened in Patrick as a result of him chasing his own aspirations.”

Complacency vs. Consciousness Development

As we glance at the motivations behind the acts and aspirations that inspire us to innovate—one major trapping of innovation is the draw towards complacency.

“The problem with technology is that it amplifies as much our desire to grow as it does our desire to be complacent,” Kentaro says. “It's very easy to distract yourself with a technology and do things that are in no way contributing to consciousness development, but meet other desires that we have as people. I think one of the big dangers is exactly the one that many people have feared about mass media all along. We are rapidly becoming a society, in which we're so busy entertaining ourselves that we don't have the time to think about consciousness development.”

At the start of the call, Birju noted that he uses an ‘insight timer’ app on his phone to remind him to meditate.

“If you already believe that meditation is important, any system that reminds you to meditate is going to help you do it better. But those systems are completely powerless to change the mind of somebody who doesn't believe in meditation,” Kentaro discerns.

He offers another example of gamification in education. As adults, some of our productivity and capacity in doing our jobs are dependent on our ability to do mundane tasks—and to push through the boredom so that we can achieve those results-- whether it's reading documents, or writing documents, or coding tedious parts of software.

“Imagine if all schools are gamified.” Kentaro invites. “On one hand, those kids might very well end up learning a lot of math, science, and history that we want them to learn; on the other hand, we would have erased a generation of kids who’ve never had the chance to learn how to push themselves through boring material,” he offers.

“It’s a mistake that we should be chasing after making life easier for everybody. What we want is to chase after the capacity for everybody to make a life better for themselves. And that capacity is a very different thing from the actual improvement.”

Such a capacity, he notes, can only be found when we develop our own human virtues—as we face our own transformations from the inside-out.

“If you are really interested in creating a better world,” he posits, “then there is something else you have to get better at, which is expression of compassion, empathy, and your capacity to do the things that you do.”

Then, with striking sincerity, he reflects, “One other thing that I am very consciously aware of myself is, however much I think I am contributing to the world, the fact is that I haven't given up a whole bunch of things that I really don't need in my life. I could easily do away 80 percent of my income and still lead a reasonable life. And yet it's very difficult for me to do that. And that suggests something internal that needs to change and is hard to change.”

Yet, Kentaro allows, “If we can help cause exactly that kind of change in ourselves, as well as in other people, and the rest of the world, then the world itself becomes a better place.”

In a conversation that raises more questions than answers, from a man who’s walked to the cutting edge of technological innovation and back, there’s a resounding conviction in the potential that lies in our own human capacities to give rise to a greater good.

ServiceSpace.org is an incubator of gift-economy projects that is run by inspired volunteers. Its mission statement reads: "We believe in the inherent goodness of others and aim to ignite that spirit of service. Through our small, collective acts, we hope to transform ourselves and the world."

SHARE YOUR REFLECTION

2 Past Reflections

On Aug 12, 2015 Kristin Pedemonti wrote:

Truth: "If we want to actually create such changes, we must look at the

intent behind the tech—the people and motivations within them that draw

us to innovate in the first place."

Here's to developing what is truly important: compassion and empathy. Certainly tech can assist in getting messages out there and in some ways evening the playing field, and as K notes, it is very much about the motivations as well as the proper overall systems that matter! Thank you for some inspiration!

On Aug 15, 2015 Mike Hansel wrote:

I found this article, incredbly inspiring. I'm sure you will to. It's brief and to the point. Check it out. http://worldobserveronline....

Post Your Reply