Frank Ostaseski: Lessons to the Living from the Dying

“Dying is much more than a medical event. It is a time for important psychological, emotional and spiritual work – a time for transition. To a large extent, the way we meet death is shaped by our habitual response to suffering, and our relationship to ourselves, to those we love, and to whatever image of ultimate kindness we hold.” - Frank Ostaseski

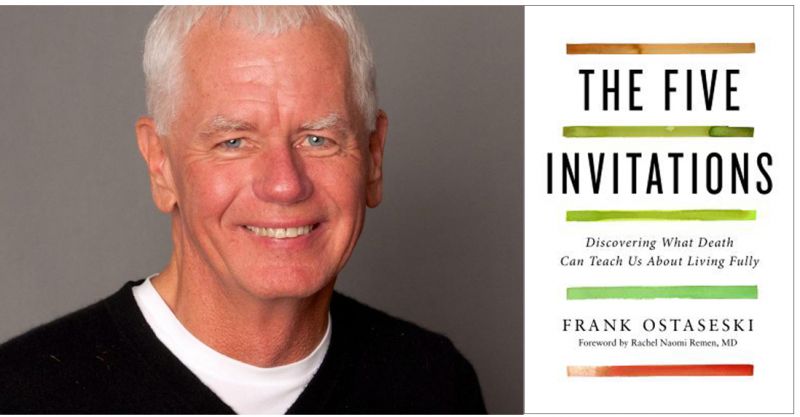

Frank Ostaseski is a Buddhist teacher, international lecturer and a leading voice in contemplative end-of-life care. He is the Guiding Teacher and visionary Founding Director of Zen Hospice Project, the first Buddhist hospice in America, in San Francisco, and also author of The Five Invitations: What the Living Can Learn From the Dying. What follows is the edited transcript of an Awakin Calls interview with Frank. You can listen to the full recording here.

Immanual Joseph: Frank, day in and day out, you deal with death and the dying. You have brought dignity and beauty to the last moment of more than a thousand people, and yet most of us shy away from the slightest discussion about death. What led you on this journey?

Frank Ostaseski: I think it's difficult to say. My life didn't progress in a linear fashion, you know. I had an early relationship with death. My mother died when I was a teenager, my father just a few years later, and so death and I were companions quite early on. When I was younger, I had a lot of pain and suffering in my life. I tried everything possible to avoid it. You have to turn toward the experience, toward what hurts, and that's where the compassion is found. For me, meditation practice was a huge part of that turning towards painful experiences. Buddhist practice and its emphasis on the study of death has been an enormous influence on my life. I also worked in refugee camps in Central America and Southern Mexico where I experienced a lot of death. When I returned to the States, the AIDS epidemic had exploded. We didn't know what we were dealing with, and so, lots of friends and colleagues were dying. We jumped in to try and take care of people. In the beginning, we worked mostly with folks who were living in the streets of San Francisco. If we were going to be of any service to them, we had to really see our own relationship to the issues of sickness and death. It was a fusion of spiritual insight and practical social action. I thought there was a natural match between people who were cultivating the listening mind in meditation practice and people who really needed to be heard at least once in their life, folks who were dying.

Immanual: I want to congratulate you on your recent book, ‘The Five Invitations: Discovering What Death Can Teach Us About Living Fully.’ These five invitations that you write about are incredibly powerful life practices. Wha0t led you to write this book and how did you settle on these five invitations?

Frank: I have to really give credit for the book to my wife, Vanda, whose idea it was to write the book. As an anniversary present, she gave me the services of a wonderful editor, MieMie Fox, who helped me develop a proposal for it.

The Five Invitations, I actually wrote in an airplane. I was invited by Bill Moyers, a world-renowned journalist, to come to Princeton to help orient and teach his staff who were preparing for a television series called ‘On Our Own Terms’. I prepared a talk to give at this conference, and I was thinking about the lessons that people who are dying have taught me. I wrote down these five phrases on a cocktail napkin and stuck it in my shirt pocket. When we came to the event, I was on a panel with some renowned experts, and they had a lot of things to say but used up most of the time, so I never got to give my talk. After the panel, Bill pulled me aside and said, "Frank, could you speak by yourself for just a few minutes about the heart of the work?" So I pulled out my cocktail napkin and delivered what I had written down. I really have to give the people that I work with and the patients that I serve for teaching me these things. They were my teachers, and so, I felt a responsibility to share it with a large audience of folks.

Immanual: We’re so glad you did, and I'm hoping that in this call you could guide us to those five invitations. Your first invitation is 'welcome everything, push away nothing'. What does it really mean to welcome everything, especially in the reality of dealing with the death of a loved one?

Frank: I think that the most important thing to understand about this invitation is that the word “welcome” actually challenges our notions and our judgments about what's acceptable and not acceptable. “Welcome everything, push away nothing” doesn't mean you have to agree with it, that you have to like what's coming. It means you have to be willing to meet it. The great African-American writer James Baldwin said, "There are many things in life we must face that we cannot change, but nothing can be changed until it is faced." To welcome everything means to be willing to be open to the experience, and when we have that capacity we actually have more options. Now, it's of course, incredibly difficult when someone we love is dying, maybe the most difficult thing to do, save perhaps our own death, but for some even more difficult.

Death is difficult. It's messy and it's painful sometimes, but most of all, it's normal. When we learn to turn toward the experience, we turn toward what it has to offer us. When we know that life is absolutely precarious, then we understand just how precious it is. We want to jump into our life with both feet. We want to tell people that we love them. It’s the precariousness of life that shows us what's really important, what really matters. So, to welcome is to include, and to say, "Oh, this is part of life." What can I do with it? What can I learn from it? How can it help me to love more?

Immanual: That’s such a difficult attitude to cultivate, and I'm wondering if you have any shortcuts.

Frank: I think one of the things that we get caught in is imagining that there's a quick fix for just about everything. These are the big challenging issues of our life, and there aren't simple answers for all of them. What's important to recognize is that all of us have the capacity to meet the suffering of another individual, to embrace it as our own and address these kinds of really challenging issues. When I was a teenager, I was a lifeguard in a school for severely disabled kids. I used to teach swimming. There was one girl, Jasmine, a beautiful sixteen-year-old, who would have been the homecoming queen of her school, except that she had spina bifida. She was too self-conscious to get into a bathing suit and come into the pool, but she loved to watch, make wisecracks, and flirt with the lifeguard. She would come to the pool every few days, and I spent months encouraging her to give swimming a try. When someone believes that they are beyond love, you can't convince them to love themselves...but you can show them that they are loved.

One day Jasmine came to the pool and took off her orthopedic shoes and braces, and she slipped her feet onto the side of the pool and dipped her toes in the water. Six months later, she showed up in a turquoise bathing suit, and without any prompting, she moved her body to the pool, called me over, and leapt into my arms, like a seven year old. It was just beautiful to see. Here’s the thing that's really important for me about the story. I mentioned earlier that I had a difficult upbringing as a child. I always held up the hope that someday, someone would rescue me. I imagined that I would be saved by love coming toward me, but it was just the opposite. I was rescued when love came through me. Love has been my mentor all along. This has enabled me to do this work for 30-35 years now without ever burning out because I know the source of my actions is love and compassion.Immanual: That is so powerful and reminds me of something I read once attributed to Mother Theresa, that ‘We are pencils in the hands of god’. Thank you for sharing that. Another invitation that you have in your book is to bring your whole self to the experience. How is possible to live fully when we know that everything is impermanent?

Frank: I think that we like security and the known, but what we are given is actually uncertainty; we are given constant change. That's in the very fabric of existence. To deny the reality of that is to cause ourselves a lot of pain.

Instead what would happen if we turned toward this experience? I think that we rely on impermanence, that really boring dinner party that you are going to go to tonight, it's going to end. Great dictatorships will fall and be replaced by thriving democracies. George Harrison, the great singer, reminded us that all things must pass. I think that to live in harmony with this basic truth and to realize that our nature and the nature of the world is not fundamentally different becomes a liberating opportunity rather than a threat. Without impermanence, your children wouldn't grow up. Pain would not go away. Our problems would never be resolved. So we need it.Many years ago, when my son was 4 or 5 years old (he's a grown man now), I had a preschool with a friend of mine, and we used to take the children to the woods to find dead stuff. They'd pick up a rusty old car part or a dead leaf or a twig or some bones, perhaps from a dead animal, and we'd gather them up and put them out for show and tell. The children were so curious about this. They weren't at all afraid of death. They had great stories about how this piece of bark was a bed for a mouse and the rusty old car part was part of a space ship that had fallen down from the sky. One little girl said to me, ‘I think the leaves that fall from the trees are so generous to make room for the new leaves.’ I wish as adults we could recognize that everything is changing in the world. Seasons come and go. Everything's changing except me, right? Well, No! When we do that we pull ourselves out of the stream of change. We isolate ourselves and become frightened. When we recognize that we are in the stream with everybody else, we are kinder to one another. I think it engenders a certain kind of letting go, a willingness not to take ourselves and our ideas so seriously.

Immanual: "Not to take ourselves so seriously," I think that is a lesson that we can all agree on.

Frank: I can certainly get caught up in that, thinking my views and opinions are the most important thing.

Immanual: The invitation that I wanted to come to, "Don't wait" - is a simple yet profound invitation. Can you share your insights on this?

Frank: “Don’t wait.” Imagine, first of all, that at the time of our dying that we will have the physical strength, emotional stability, and mental clarity to do the work of a lifetime is a ridiculous gamble. As we've just been talking about, when we embrace the truth, it encourages us not to wait. We learn to hold our ideas and identities a little less tightly. Instead of pinning our hopes on a better future, we focus on the present. I think "don't wait' is a pathway to fulfillment and an antidote to regret. By "don't wait" I don't mean to suggest that it is a way of getting all the toys -- that's a mistaken notion. "Don't wait" means don't imagine you have limitless time, and don't wait to go toward what you love most. Mostly we imagine death will come later, but constant change is not later, it's now. Don't wait is a kind of invitation to really step into our life with both feet.

Immanual: I wanted to reflect on a question that one of our call participants asked on our chat page: “How do you deal with death and dying? How can we avoid compassion fatigue, and how can we find spaces for self-compassion?”

Frank: Well, that's a big question and I have to begin by saying that I think "compassion fatigue" may be a misnomer. I think what people are calling "compassion fatigue" is a kind of “empathetic overload” where they get so entangled in the suffering of another that they can't separate themselves out. Compassion is something a little bit different than that. Empathy is "I feel with,” and compassion is "I feel for." So, I can sit here and have an empathetic relationship with you and the suffering that you've experienced, but I can also have access to my own wisdom and skillfulness so I can be some real support in actually eliminating or at least reducing the suffering in your life.

The other is to realize is that I come from a Buddhist tradition, and in that tradition there are all kinds of treaties on the subject of compassion. I tend to boil it down to two things. I think of what we might call universal compassion and everyday compassion. Universal compassion is boundless and vast. It's always been there and everyone has always been embraced by it even if we didn't know it. Then there is everyday compassion. That's when we do stuff: feeding someone on the street, or changing soiled linens in a hospice, or standing up against social injustice. What starts to happen is we get tired. We want people to start saying thank you for our good work.

Everyday compassion has to be grounded in what we can call universal compassion. It has to understand the source of it. On the other hand, universal compassion is beautiful, but without every day compassion, it's just a big idea. Universal compassion needs you and I and everybody on this call so that it can express itself in the world. That's how it manifests.My friend Bernie Glassman is a brilliant Zen teacher. He was teaching in Germany a few years ago and talking about the Buddhist deity of Avalokitesvara. She is the deity of compassion and has a thousand arms, and in each hand, either an ear or an eye to see the suffering of the world or to hear the crying in the world and a thousand arms to respond with. Bernie was talking about this and a man raised his hand he said, "That's all well and good but I only have two arms. What should I do?"

Then Bernie said, "Well I'm sorry, but you're mistaken." The man looked at his body and said, "No, I'm quite certain I have just two arms." Then Bernie did a beautiful thing. He had all the people in the room, and there were more than five hundred people in the room, raise both their arms. There it was--a thousand arms in the room. We're always imagining we have to do it all by ourselves, and we can't do it by ourselves. We need each other. That's what's so beautiful about what’s happening here today on this call. Everyday compassion is grounded in universal compassion, and universal compassion needs our arms and legs to do its work in the world.

Immanual: One of the other five invitations that you write about is to find a place of rest in the middle of thing, and yet we live in a very restless world. How can we find rest in the middle of things?Frank: Well you're right. We have an awful lot of encouragement to go go go. We've lost ourselves in this process. We will get rest when we go on vacation, or when our list gets checked off, or our email box is empty. If I wait for that, I'm in trouble. I have to learn to find rest right in the middle of what I'm doing, and we do that by by bringing our attention fully and completely to whatever it is that we are engaged in.

There was a woman at the hospice named Adele, and she was a cranky, grumpy, wonderful eighty-six-year-old Russian Jewish lady and a no-nonsense woman. The night she was dying, I came into the hospice at about three in the morning, and she was sitting on the edge of her bed in her hospital gown with a home health aide. I went and sat in the corner, because that's my habit to see if anything is needed before I jump in to help. I saw that she was breathing with great difficulty.

The home health aide said "Adele, you don't have to be frightened. We are right here with you."

Adele, turned toward her she said, "Honey, if this was happening to you you'd be frightened."

A little while later the home health aide turned to Adele and said, "You look a little cold. Can I put a shawl on you? Would you like a blanket around your shoulders?" Adele shot back, "Of course I'm cold--I'm almost dead."

I was watching this in the corner, and I saw two things. The first thing was struggle. There was a labor to dying. The second thing was that she didn't want any nonsense. She didn't want to talk about tunnels of light or after-death experiences. She wanted something real and authentic. I pulled my chair right up in front of her, looked her in the eye, and said, "Adele, would you like to struggle a little less?" She said, "Yes."

I said, “I notice you’re having difficulty breathing. I'm wondering what it would be like if you could put your attention on that little pause between the exhale and the inhale,” and she agreed.

I said, "Good, I'll do it with you." I didn't lead her. When she would breathe in, I would breathe in, and when she would breathe out, I would breathe out. We did this together for a while. As she put her attention there on that pause between the exhale and the inhale, the fear in her face just drained away, and she began to relax. A little while later, she laid back in bed and said, "I'm just going to rest now." She later died in a peacefully. She was still dying, but she found a new relationship with death. Adele found a place of rest in the middle of things. We can do that in our lives, but we have been so acculturated to try and change the conditions that we never think how we can be in those conditions.

I work with a man who was the head of a very large tech company in Silicon Valley. He was very troubled, and when I asked him what he did during his day, he said mostly he would sit in a board room, and people would come in from different departments and give him reports, and he’d comment on them. I asked him when he used the bathroom, and he said not frequently. I then encouraged him to take a “bathroom break” every hour. He went into the stall where he would sit quietly for a few moments. The bathroom stall became his meditation hut. He would go there and find stability, and then he would come back to his meeting. After awhile he could just do that in the midst of his meetings. So how can we find a place of rest right where we are in middle of our lives?

Immanual: I totally agree - and I think this idea of bathroom breaks for mindfulness should be promoted to everybody!

Frank: There you go - there’s a quick fix! I talk to doctors and nurses all the time, and they are trained to override their bodily urges and to go without sleep for days at time. When you think about it, there’s this kind of investment in being exhausted in our culture. When we tell people -- Oh I’m so busy -- what do we want from that? We want people to admire us for our exhaustion, or to imagine that we are really dedicated to what we do. I think that’s a sign of imbalance, not maturity.

Immanual: There is so much divisiveness and hurt in our current political climate, and I’m curious how the awareness and acceptance of our own impermanence can help us with dealing with the divisiveness and hurt that we are dealing with.

Frank: I think we really have to honor how difficult it is. The world is suffering now. It is difficult to stay engaged when there are so many forces pushing us in different directions. When we recognize the precariousness of life, we understand that we are in the boat together. This helps us to see that death, grieving, loss, and constant changes are common ground. Fear is also one of our common grounds. Death comes to prince and pauper, and a reflection on death is not morbid or depressing; it’s life-affirming. The willingness to contemplate death is not just about preparing for some moment at the end of a long road. I think it’s a compassion practice to read the newspaper, to read about the suffering of our world.

Immanual: I think a lot of us kind of get caught in that space between just following compassion or being wise and don’t find the balance there.Frank: In many countries and spiritual traditions, you have Namaste or Gaisho or bringing the hands together in prayer. In the Buddhist tradition one way we think about that is when you bring your right hand or left hand into a prayer position, the coming together of wisdom and compassion is a recognition of inseparability. We can appreciate our diversity without needing to separate in order to have that.

Immanual: I have a question for your about the fifth and final invitation.. What is the ‘Don't Know Mind’ and how do we cultivate it?

Frank: I felt obliged to put something zen-like in this list so I used this phrase. To cultivate a Don't Know Mind is not about cultivating ignorance. Ignorance is a misperception of reality. Don't Know Mind represents something else entirely. It represents the mind that's not limited by genders or rules or expectations. It’s free to discover, and when we are filled with that knowledge, it narrows our vision. We only see what knowing allows us to see. A wise person is compassionate, humble, and knows what they don't know. The cultivated 'don't know mind' is not about cultivating ignorance; it’s about cultivating a sense of receptivity, curiosity, discovery. This is what enables us to enter our lives with fresh eyes.

Immanual: How do we cultivate it?

Frank: It’s about a willingness to express that we don’t have all the answers. We are not throwing away our knowledge. It's there in the background, but we don't get fixed on ideas. We let go of a little bit of control. To cultivate a 'don't know mind' is to cultivate our sense of curiosity. Let me give you an example: let’s say you are in California, and you want to hike to a mountain lake that you love, but it’s a long journey up the mountain.It's not enough to love the lake; you also have to like the walk up to the lake. Otherwise when the mosquitoes come out you'll turn back.

Love is the kind of fuel for the journey that gets you up the mountain and motivates you along the way, but there is something else. If love is the fuel for the journey, joy is the spark that ignites the fuel. You know when you see children play, they don't play for a purpose, they just play to discover, they just play to have fun. I have a two year old granddaughter, and she is all about discovery. I love being with her because it challenges my way of seeing things. What if I find joy? So can we take something that we think is absolutely horrible, and make it nice? I’m not trying to make a Hallmark Card out of life. But to really look and see, how could I see this from a new perspective? What might that new perspective have to teach me?

Pavi: Thank you so much Frank and thank you Immanual. I wanted to read one of the comments from our listeners, Laura Crowed. She says: "When my 28- year-old-son died in a motorcycle accident, just three weeks since moving home to finish his Phd, I learned what being sick to death actually means. I cried non-stop for weeks. On one of those occasions I was outside in my garden. I couldn't take a deep breath and felt as if I was having a heart attack. In a flash I felt something that I can only describe as a crack in my chest. I could feel the earth moan and sob with me, and for a moment I thought I had lost my mind. I could feel what all mothers who lost a child feel, and I knew I was not alone, in my suffering.

Shortly after I read a quote: ‘The heart that is open never breaks.’ In that instant, I believe, my heart was split wide open. The loss of my son opened me to the suffering of all beings and I felt a strange peace.”

Frank: Laura thank you for that, that's just so beautiful! I love what she said about the heart breaking open, you know. When people would come to volunteer at our hospice, one of the questions I would ask is: 'Are you willing to open your heart and have it be broken?’ It’s the most beautiful and difficult thing to be a human being.

Pavi: Thank you Frank. I am going to jump in with a couple of questions here as well. In the process of this work I imagine that denial is something that comes up often, either in patients or in care givers, and I was wondering what you feel to be the role of denial?

Frank: I think that we have this aversive relationship to denial in our culture. People are always trying to get others out of denial, and I am like 'don't take it away unless you have something better to replace it.’ First of all, denial at a certain stage of our experience is necessary. It's a protective device. It allows us to assimilate and metabolise some experiences that are too shocking for our system. Now denial promoted, over a period of time, just breathes ignorance and fear. I can't be free if I am rejecting any part of my experience.

A woman died in our hospice while her sister was down the hall in the bathroom. When the sister came back, I said: 'I am sorry, your sister has passed while you were down the hall' and the woman said: 'well she is not dead yet'. Her sister died but she wasn't ready for that truth yet. So I asked, 'When was she most alive?' She said, 'When she was a youngster, she was a spelunker and she went in a caves, and she was a great adventurer. Then, she found this political magazine and was a firebrand.’ She kept going through the story of her sister's life, until she said, 'We went to the hospital last week, and the doctor said that he couldn't do any more chemo, and now she is here, and then she was getting weaker and weaker and she stopped eating.'

Her sister then came to the current moment. We talked about washing her body and taking care of her. She wasn't ready, so she had to tell some of the story and get current with the situation. Denial is not the enemy.

Pavi: That is a really valuable re-framing to have. It brings to mind one of the things that we talk about often at ServiceSpace. A few years ago, Google announced its plans to 'solve death'. I was wondering how you look at some of the trends in our current societal relationship to death, and where you find hope in this rushing towards an impossible eternity or eternal life.

Frank: I was speaking with a group of folks in Silicon Valley not long ago, and I said death is inevitable. One guy raised his hand and he said, “I'm not so sure about that. A lot of us in this room are working on that.” I said, “Great, let's step back from this word ‘death’ for a moment. Let's just begin to look at endings. You want to know what death has to teach -- look at endings.”

How do you meet endings in your life? Do you go unconsciously around them? For example, when you're at a gathering of friends, do you leave, either emotionally or mentally, before the event is over? Do you ghost out the door because you think nobody knows that you were there, so they won't notice that you've gone, or you are the last one in the parking lot waving to all the participants who came to the conference? Do you feel sad and teary-eyed with endings, or are you anxious and indifferent with them?

Look at the way we meet endings! That’s a really useful thing. Even if we extend life 200 years, death will eventually come. In between all that, death is not something that is happening at the end of a long road. It's in the marrow of every passing moment! The way we meet this moment, and the ending of this moment shapes the way the next one arrives. Before the Greeks, people have always had a great wish for eternal life, but I think, eternity is not necessarily a long time. St. Augustine, the great Christian mystic talked about the ‘now’ as neither being ‘in time’ or ‘out of time’. The ‘now’ is the moment of eternity. ‘Now’ is not some millisecond or nanosecond between times -- it's outside of time. We've all had that experience of timelessness. We can have that, here and now.

Pavi: That is another great reframing of death, in terms of endings. I was thinking similarly about the word ‘suffering.’ Maybe we magnify it in our heads, and as a result, separate ourselves from it. How do you define that word?Frank: We throw that word around in the Buddhist world a lot. We think of suffering as something big that’s happened to somebody else, like refugees fleeing Syria or children starving in an African country. Suffering is just our relationship to life. Suffering is when buy an iPhone, and the new model gets announced next week or falling in love with somebody and getting to know them better. All these things are suffering. It’s our relationship to conditions. One of the ways to talk about suffering is that we have different kinds of relationships to life. One way that we suffer is that we demand that life be different than it is. It’s this unquenchable thirst that things be other than they are, and so whatever is here is not enough. Then there's the opposite of that, which is a kind of aversion to life as it is -- we don't like the way things are, so we make an enemy out of everything and everyone. We stay in this perpetual cycle of suffering. The third is ignorance, and it’s the biggest form of it. Ignorance is not really seeing the way life is, and so I keep tripping and falling into the same hole.

Pavi Mehta: Listening to you talking about the work that you’ve done in a very specific realm of life feels like it applies to almost every dimension. I'm sure your book has reached all kinds of diverse audiences. Have you been surprised by any of the unexpected corners that have been receptive?

Frank: Again, I have to really give credit to my wife, because she's the one who really saw that there was a whole audience of people that could really benefit from the wisdom that we learn at the bedside of people who were dying.

I gave a talk at a program called ‘The Long Now’ in San Francisco, created by Stewart Brand, the Futurist. It’s normally a program for people who think in terms of trends -- 10,000 year trends. The audience for it is usually people who come on their laptops and iPads. It was really interesting to see everyone closing their laptops and putting away their iPads. They were riveted because the subject was so galvanizing. Death cuts through all of our pretensions and shows us what really matters. We don't have to wait until we're dying to learn the lessons that dying has to teach. That's why I wrote the book! It's about what you learn from dying that could help you live a life of meaning and integrity, a happier life.

Pavi: Wonderful! I have more questions, but I’m going to go to the caller in our queue.

Kozo: Hi, this is Kozo from Cupertino. And thank you so much for this call and the five invitations, Frank. I wanted to ask you a question about one of the invitations -- welcoming everything and resisting nothing -- but from a different point of view. I know a lot of that is dealing with people who are dying, and I’m wondering if you have ever seen it the other way around -- where people who are dying, are almost giving up. I think about some stories that I've heard where a married person whose spouse died and within 5 months, they're dead as well even though they were perfectly healthy before the spouse died. I'm wondering if you’ve experienced that or have any thoughts on that?

Frank: Beautiful question, Kozo, and thank you for bringing it up. I think this last part that you just mentioned is a really common phenomenon. You know partly it's also a result of the fact that they usually work really hard to take care of them, oftentimes sacrificing their own health in that process. There are multiple factors that lead to that outcome.

Yet, we know that there are some people in life who see death as the best solution for their problems. Life has become desperate and unlivable in many ways for them, and so they see death as a way to bring all that suffering to some kind of closure. I'm not so sure that we can promise people that death will end all our suffering.

There was an old Italian lady in our hospice, and whenever you would ask her, “How are you today?” She’d say, “Oh, I just want to die.” We had a running gag in the hospice and I said, “Well, you're not taking her seriously!” So I went and asked her, “How are you today, Grace?” She said, “Oh, I just want to die.” I said, “Grace, what makes you think that dying would be so good?” It was a counterintuitive question to ask. Grace said, “Well, at least I’ll get out.” And I said, “Get out of what, Grace?”

Grace was a devoted wife to her husband who was a truck driver. Every day she'd laid out his clothes, paid the bills, made all his meals, and when she was sick she couldn't imagine that he could take care of her, nor could her daughter. She was the giver, so she came to the hospital expecting she would die quickly. All I know is that a few days later Grace moved back home. and she lived in the care of her husband and daughter for another six months and died comfortably.

I think that sometimes it's really useful to inquire with people to let people know how much we care about their presence, and to really value the enormous healing power of human presence, which I sense you have a sense of Kozo.

Kozo: Thank you.

Pavi: Frank I feel like the work that you do calls out the ways in which we might be bluffing to ourselves about how we are serving, and to serve at someone's death bed requires a kind of authenticity. What has serving in this way taught you about true service?

Frank: That’s a great question. I was overzealous in the beginning, I thought I knew what was right for everyone else. A few years ago I had a heart attack when I was teaching a retreat for doctors and nurses, and that was really a great teaching. It was humbling, and I really saw what it was like to be on the other side of the street. One of the things that I learned in the course of my work is the value of humility. The other was to see myself in the other person, and I don't mean in some kind of a psychological projection. I mean to really see my own mother in this woman, Grace, that I was speaking of, and to see myself in her. This fundamentally shifts the way in which I serve. For me, service has always has always been about mutual benefit. To me, true service is to recognize the mutuality of this experience.

In Zen Center there is what they call a mountain seat ceremony when the new Abbot is installed, and students come forward and ask seemingly combative questions to test capacity to lead the community with compassion. At one ceremony a student came and asked, “What does spiritual practice have to teach me about taking care of others?” The Abbot shot back in a very Zen way, “What others? Take care of yourself.” The student responded, “Well how do I do that? How do I take care of myself?” And the Abbot said, “Well of course -- serve other people.” In other words: we’re in this boat together.

Pavi: That reminds me of the Dalai Lama’s quote, “Be Selfish. Be Generous.” I am going to our next caller here.

Alyssa: Hi, this is Alyssa in Seattle, and I want to thank you. This has been an absolutely amazing call. I have two questions. When you were speaking of endings, you said how you shape and deal with endings is how you can shape and treat the new beginnings. I wondered if you could go more in depth what you meant by that.Frank: The way in which we end one experience shapes where the next one begins. For example, you just had an argument with your partner or your best friend, and then you have to step into some other situation. What has been unresolved is there with you; you carry into the next moment. When I am in a hospital and move from one patient's room to the next, I have to make sure I bring some honorable closure with the patient in the room, even if they are in a coma. I then have to consciously step into the next room. I have this silly habit, when I go into a patient's room I look to see where the hinges are on the door. If they are on the right I step in with my right foot. It’s a way of me entering the room mindfully -- recognizing that I am crossing a threshold into a new world. Now we can’t always make it fully complete, so we have to promise ourselves we will come back to that later. I am angry now or I am upset now, but I am going to come back to later. It’s not compartmentalizing-- it’s a promise.

Alyssa: Yes -- I’m having to move and thinking of how I’m being when I am moving and going to the next place. It’s shifted my perspective and how I am dealing with it. Maybe I’m choosing something like openness, just being open and having that perception.

Frank: Right!

Alyssa: The other question I had was - it seems what I am hearing is that throughout there is this incredible - I don’t know if it is a gift you have - but of having in your story the right questions and actions. A lot of it seems like you have this incredible skill from your experience, but in your stories I was wondering if a lot of this comes through, not from you?

Frank: That's a very good way to say it. I think that you know when we're present and present means first of all I'm here, I'm available, my mind is not scattered. Presence is some other way to fullness of mind, and it has a palpable quality to it. Most of us have had some experience like this, and we tune in and make sense to a kind of inner guide. That inner guidance is coming from some archangels, and that might be someone's belief. In my case, it feels like it's an innate human quality that rises up in response to the situation. Curiosity arises as a kind of guidance; playfulness arises as a kind of guidance. These are essential human qualities that we all have in us. The challenge is to get quiet enough to be able to listen, to not be so full of our knowing that we don't actually tune in or listen to what it is that is emerging. That might be of real benefit in the situation. I sense that you are able to do that. You quiet yourself, calm yourself, and then see what you might intuitively know that wonderful sixth sense of intuition.

Pavi: Frank, what comes up for me listening to you and thinking about the stories and experiences that you've borne witness to is how you work with all that in such a way that it doesn't weigh you down. Is it the honorable closure you experience in your practice that allows you to not be paralyzed.

Frank: Sometimes I get lost, and that's just human. We're going to get lost and overwhelmed. We're going to get swept away by our sadness or grief, and I think to recognize that when I'm with somebody else who's suffering I am enabled to look at my own fear. I'm looking at my own grief all the time, so it's not like I'm one hundred percent over there with them. I'm actually keeping a percentage of my attention in my own experience. Second, I have to do practices which can help keep me balance. In the midst of the AIDS epidemic, sometimes I knew twenty, thirty people died in the week. It was an enormous source of grief in my life.

I would do three things to cope. The first thing is I went back to my meditation cushion to stabilize this experience to gain perspective. The second thing I did was visit a body worker once a week, and he was a really great guy. I would walk in his office and lay on a table and he would say, “Where should I touch today Frank?” I would point to my shoulder. He put his hand on my shoulder, and I would just weep for about an hour. I would get up from the table, and I would say see you next week. We hardly ever had a conversation. It was just that I needed that relational touch to help me contact and feel free to express the sadness that was in my life.

The third thing I did was I used to visit the maternity ward with some friends of mine where there were babies who were born to addicted mothers. These babies needed to be held, and so before I would go home to my own children, I would go to the hospital and hold these babies. I just stayed there with a loving presence to calm them down so they would be able to sleep. There was something about that tenderness and ability to nurture little babies. This helped me enormously in working with the suffering. Those practices were essential to me in that work to keep them kind of balanced and stay human and not become a technician.

People are doing this all over the place, and we talk about the problems of health are but gosh, I wish I could share with you the stories I have of nurses, home health aides, doctors, and social workers doing remarkable things beyond the scope of their job. One time, I witnessed a nurse’s assistant with the grunt job. After a code blue, his job was to clean up the room. The patient was still there, and he walked over to the patient, leaned over, and said, “You've died now, and I'm going to as respectfully as possible wash away all dust and confusion and bathe her body.’ We need to know that that kind of basic goodness is there.

Pavi: We have many people in this community work with at risk youth and children who have been going through all kinds of trauma, and I wonder, as someone who survived a troubled youth, if you have any words or guidance for them.

Frank: The complexity of trauma that children at risk are living through these days is devastating. It is mind boggling that people can still be walking around, but I only tell what helped me. Just love them until they can love themselves again. People loved me and showed me that it was possible to love myself, and so I borrowed their love.

Pavi: You mentioned the fact that the dying process is not a medical process, and it does its own work just like the birth process. Can you speak a little bit more about that?

Frank: We treat dying in this country and in many countries as if it was simply a medical event, and it is so much more than that. It is so much more profound, and there is no one single model that is large enough to embrace all that happens at the time of dying. Dying is much more about our relationship through love to suffering the experience of death itself to God or whatever image of ultimate kindness we hold. The work of being with dying is about attending to those relationships, and the first characteristic that we need in that relationship is mastery. We need to know what we're doing. I want a doctor and nurse with me who can manage my pain and control my symptoms. I need that but that won't be enough.

I need somebody who's going to be comfortable in the spirit of meaning to help me find out what the purpose and value of my life is. We trust and know that there are certain conditions in the dying process that are conducive to helping us wake up to our life. It strips away all of the identities and then we can now do something far more essential in our lives, something much more fundamental, true, and real. Dying shows us that we have a full rich life and again hopefully we step into our full hearts.

Pavi: What a profound reminder and inspiration to close on. We do have one final question that we ask all of our guests and that is, how can we as the extended ServiceSpace Awakin Call community serve you in what you're doing?

Frank: Serve me! Dying is an ordinary experience in that none of us get out of here alive. Let’s turn toward it, sit down with it, have a cup of tea with it, and get to know it really well. There's museums where there are great paintings hanging where we go on and on about a great artist. We want to be such places in our communities where people come to die, when we come to them we say, “please tell us how to live.” There's so many people living in nursing homes and residential care facilities that are totally alone. Go to one, sit next to somebody for a while and stare out the window with them.

Personally you're very kind to mention this book, the “The Five Invitations” -- Buy it. I don’t need the money, but buy it, read it, share it with your friends. Get a group of people together, and talk about it. If you go to our website, there is a how-to guide for starting a book group. I wrote it to help people step more fully into their lives.

Pavi: We will definitely send out the links to the website and get the resources that you mentioned to all the people on this call. Before I close with a minute of gratitude, I wanted to say that it felt like speaking with you I wasn't just speaking with you. I felt like the spirit of all the people that you helped transition, all the care workers that you worked with, your wife who prompted you to write the book and get these messages out in the world was with us. Thank you for bringing them all into this conversation and enriching our lives through your generosity Frank.

Frank: They're my true teachers.

This interview was edited by Abigail Hardee. The full-length version of this interview is available at Awakin.org. Awakin Calls are weekly conference calls that anyone from around the world can dial into at no charge. Each call features a unique theme and an inspiring guest speaker.

SHARE YOUR REFLECTION

5 Past Reflections

On Jan 27, 2018 Kay L wrote:

My small and intimate book group has been reading the book and everyone is enjoying the gifts of this author immensely! I will be reading this again and again! I also work in Hospice and this book has inspired me deeply in many ways.

On Jan 26, 2018 mack paul wrote:

Really great interview. I've learned a lot about death by loving and watching my pets live and die. I lost two sixteen year old dogs who had to be put to sleep and I found myself feeling guilty over doing it and guilty over waiting so long. But their emotions are so much like ours in their desire to be with their loved ones and they keep living right up until the last moment.

On Jan 26, 2018 Stef wrote:

A beautiful conversation, true lessons for life (and death). "Don´t wait", "step into life with both feet". What a peaceful and active statement. Very grateful for this conversation. Thank you.

On Jan 26, 2018 Patrick Watters wrote:

As a "Christian Buddhist" (a contemplative), I appreciate the love of this discussion. Timely after witnessing the passing (walk on) of my 94yr old mother-in-law. Peace, shalom even. }:- ❤️

On Feb 5, 2018 shadakshary wrote:

Inspiring article.Thanks a lot

Post Your Reply