The Strangest Social Justice Story

15 April, 1951. India was burning with a communist revolution where the landless had erupted violently against centuries of exploitation by landlords. The communist leaders in Telangana had been arrested by the government and were in jail. On this day, they were surprised to hear that someone had come to see them. Their elderly visitor was a strange skinny man with a beard, who was interested in their well-being. He had come a long way to talk to them and challenge their views on communism. He listened deeply to what had turned them onto communism, and then presented his views with so much love that something shifted within these young men, who then agreed to create space for nonviolent resolution of their grievances.

That strange visitor was Vinoba Bhave, the spiritual successor of Gandhi, and this conversation was a precursor to a remarkable social justice movement that is outside the frame of reference of even the most indomitable optimist. Who was this man? When was the last time you heard of a modern leader jumping into the eye of a storm, to meet opponents who are strongly indoctrinated and attempt to transform them with love? Before we dive into Vinoba’s story, let’s back up a little bit and go to his teacher, known to the world as Mahatma Gandhi.

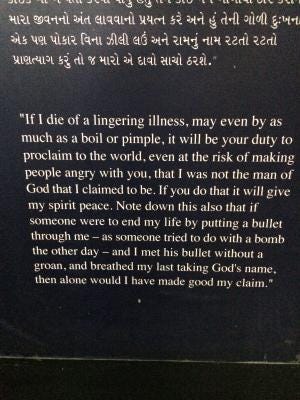

The quote at Gandhi Ashram, Ahmedabad

Gandhi had once said, “If I die of a lingering illness, may even by as much as a boil or pimple, it will be your duty to proclaim to the world, even at the risk of making people angry with you, that I was not the man of God that I claimed to be. If you do that it will give my spirit peace. Note down this also that if someone were to end my life by putting a bullet through me -- as someone tried to do with a bomb the other day -- and I met his bullet without a groan, and breathed my last taking God’s name, then alone would I have made good my claim.”

Very few people get to take their hardest tests, and even fewer succeed. Mahatma Gandhi got his test, and it is said that he departed not with an “Oh no,” but with a prayer. He was a human whose doing and rationalization of non-violence was far exceeded by his being of it.

Gandhi was deeply influenced by the Jaina philosophy and the Bhagvad Gita, as he was brought up in a part of the world that was steeped in these traditions. His own understanding on non-violence was quite sophisticated. He felt that non-violence in action was superficial, and that the real problem was violence in the mind that arises by not understanding one’s own nature.

Known for being provocative at times, Gandhi would exhort those with a superficial understanding of this doctrine to adopt violence instead and go shed their blood in a war. After they had tasted blood, they would have earned the right to become strong followers of non-violence.

He held Khan Abdul Gaffar Khan, a Pashtun leader from the North West Frontier Province (now a part of Pakistan), who became a non-violent soldier of Islam, as his hero. Gandhi would tell people that Khan’s non-violence was of a much higher character than his own, owing to his being born in Afghan society which had a long tribal history of violence and revenge.

Gandhi today evokes admiration in the west and a complex range of emotions in his native India. While many fault him for India’s myriad woes, even his harshest critic would reserve personal admiration for his integrity and fearless adherence to nonviolence.

India has seen many saints of nonviolence, of which Gandhi was no doubt a modern giant. Yet, reducing his life to nonviolence is misstating his biggest contribution, one that is seldom acknowledged. He saw unity in all existence, even in those he opposed. While it is one thing to say this in theory, the wisdom that arose in him through this approach is particularly relevant to us today in matters of social injustice. Nowhere is this more apparent than in his disagreement with another great hero of India, Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (or Babasaheb as he is fondly remembered).

Ambedkar, who belonged to a caste that was discriminated against, had to face much anguish in life. He revolted against the exploitation that he and India’s Dalit community faced at the hands of the upper castes. As part of his activism, he advocated violent agitation against the landowners. He wrote, in a book titled Gandhi: The Enemy of the Harijans, “Mr. Gandhi does not wish to hurt the propertied class. He is even opposed to a campaign against them. He has no passion for economic equality. Referring to the propertied class Mr. Gandhi said quite recently that he does not wish to destroy the hen that lays the golden egg. His solution for the economic conflict between the owners and the workers, between the rich and the poor, between the landlords and the tenants and between the employers and the employees is very simple. The owners need not deprive themselves of their property. All they need do is to declare themselves trustees for the poor. Of course, the trust is to be a voluntary one carrying only a spiritual obligation.”

In all of the writings praising Gandhi, I have never found sweeter praise than this harsh and legitimate criticism from Ambedkar. In it lies a great secret that Gandhi had discovered. There is value in everything. Even in those who exploit. Throwing the baby out with the bathwater is a sign of imbalance, often due to aggravated emotions. Gandhi was encouraging us to think with a cool head and a warm heart.

Ambedkar no doubt thought that Gandhi was being naive. Neither man lived to see the outcome of Gandhi’s approach. But we did. China had started its first of many “land reform” campaigns in the lifetime of Ambedkar, from 1947 to 1952. Peasants were encouraged to rise against their landlords and kill them. That campaign resulted in approximately 1–4.5 million deaths. The peasants were organized into cooperatives, collectives and finally people’s communes in an experiment to match the productivity of the west. According to historians, the intense artificial pressure to make the experiment succeed had cost at least 45 million lives of workers who either starved in the famines that resulted or were beaten to death. By 1962, the government gave up and started importing grain. The communes were abolished and private ownership of land was reinstated.

Since 2000, Zimbabwe also followed a similar path, by kicking out white landholders against whom the indigenous population had legitimate grievances. The government there saw the “redistribution” of white-owned farmland as a fulfillment of social justice for the blacks. While more blacks now own land in Zimbabwe than ever before, the result of throwing the baby out with the bathwater has been traumatic. With neither knowledge nor interest in running the farms, the new occupants were unable to maintain the intensive industrialized farming of the previous owners. Short-term gains were sought by selling farm equipment, and with the white farmers gone, a major asset had become a liability. The story of Zimbabwe’s devastation since 2000 is barely captured by the ignominy of being ranked the third poorest country in the world by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in 2013.

On the other hand, we also have the stories of India and South Africa where revenge in the name of social justice was resisted. In India, in the wake of a communist rebellion against landowners in 1951, there were riots in Telangana, in what was then the state of Andhra Pradesh and is now its own state. Vinoba Bhave, Gandhi’s spiritual successor, determined that he would try to bring about a positive change in the situation. He walked through the affected region, talking to the masses to understand their problems. What is truly remarkable about this is that Vinoba could not speak the local language and relied on a translator. He also met with the communist rebels and convinced them to renounce violence. What happened next is the stuff of legends. In a meeting in Pochampalli, 40 landless families who worked as laborers on farms declared that if they could get 2 acres each, or a total of 80 acres of land, they could work the land and make a living. Vinoba asked if they would work it together instead of getting separate holdings. They agreed. He then wanted to make a petition to the government on their behalf. At this point, a landlord named Ramachandra Reddy who was present at the meeting got up and declared, “If eighty is all you need, I will give you one hundred acres.”

Vinoba was deeply moved by this spontaneous act of love, which he had neither planned nor anticipated. He noted, “All night long, I pondered over what had happened. It was a revelation — people may be moved by love to share even their land.” He then wondered what would happen if he went from village to village, requesting landlords to voluntarily give a portion of their land for redistribution to the landless, and thus was born Bhoodan (pronounced bhoo-daan), or land donation. Bhoodan became the biggest voluntary land donation project in the history of mankind. Four million acres of land were donated through this project. In the first six years alone, enough land the size of Scotland had been acquired. Hallam Tennyson, who walked with Vinoba, notes in the book Moved by Love, “Vinoba went on foot from village to village appealing to landlords to hand over at least one-sixth of their land to the landless cultivators of their village. ‘Air and water belong to all,’ Vinoba said. ‘Land should be shared in common as well.’ The tone of voice in which this was said was all-important. It was never condemnatory, never harsh. Gentleness-true Ahimsa was Vinoba’s trademark. A gentleness backed up by a life of such dedication and simplicity that few could listen to his pleading unmoved.”

Despite its bold imagination and mass mobilization, Bhoodan has generally been judged harshly by intellectuals looking at the numbers. According to 1975 statistics, almost 4.2 million acres had been collected by this movement. This was less than one-tenth of what Vinoba had hoped to collect by 1957. That does sound dismal. Critics of Bhoodan have further noted that three-fourths of the land could not be distributed due to government red-tape or lack of arability. All of this is depressing, until we realize that it is a matter of perspective. First, the the amount of land collected was greater than the size of many countries like the Bahamas, Jamaica and Lebanon. Second, the amount of land redistributed as of 1975, was greater than what the Indian government had managed to do with its land reform programs.

Dr. Parag Cholkar gives a fascinating account of what happened next. Bhoodan morphed into a Gramdan (pronounced graam-daan), or village donation movement, based on Vinoba’s encouragement to voluntarily abolish individual ownership of land. All landholders of a village would donate their lands to the village to be collectively managed, and redistributed according to need. Those with larger families and needs would get more land. The land would be owned by the entire village and used in the interest of the village.

When the state of Assam faced riots against linguistic minorities in 1960, at the request of the prime minister, Vinoba camped there for a year and a half and worked toward peace and harmony, while also conducting many gramdans. In those days, infiltration of villages from what was then East Pakistan (and now Bangladesh) was considered a problem. Those villages that moved to the gramdan model have remained infiltration-free to this day as no land can be purchased without the consent of the entire village community. Gramdan continues to this day.

Vinoba’s work was not about a novel way to solve social injustice issues around land, although it did do that to a large extent. It was also not about organizing successful mass movements at a grand scale, although it certainly was one that captured the nation’s imagination. During the time that he was active, Vinoba had exhorted young people to experiment being the change. And millions responded for a while, where it seemed like this might really work. Over time, vested interests took over, like they’d take over any other great idea of the day. It also didn’t help matters that Vinoba had a puritan attitude toward money and those who had families to feed could not participate for long in the movement. The movement also faced many detractors amongst intellectuals, and it could not be understood by economists for its methods and language were far beyond the economic realm. Cholkar quotes Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister, as stating,

“There is no doubt that Vinoba’s movement is a somewhat strange way of solving this (land reform) important and complex problem. This is a way which the learned economists cannot explain; perhaps cannot understand as well.”

Bhoodan’s primary contribution was in demonstrating to the world that our strong assumptions about human nature being primarily exploitative are incomplete. People everywhere do respond to selfless love. Yes, they can fall back into hatred, but if love is nurtured and valued as the bedrock of a community, then seemingly impossible solutions become possible.

Vinoba has given us a compelling invitation to try the unthinkable — trust our own generosity and that of others. He did not give us cookie-cutter answers. But he did show that when we walk our talk with authenticity, amazing things happen. Things we cannot possibly anticipate. When we can’t think our way out of a problem, perhaps it is time to try loving. His love was not small. He did not include just the oppressed. His definition of community included the landlords, landless and the communists, and indeed, without the active participation of all three groups, Bhoodan would not have been possible. Vinoba even chided the nation to speed up its reforms, for he resonated with the anguish of the communists. He taught us to dig deeper into the essence of all those who are anguished, and there, his finding was that there are only universal values on which we are bound to find a common ground.

Vinoba’s trust in generosity was not passive. It would be a gross misunderstanding to think that by just assuming it, people would pour out their generosity and solve difficult problems. Vinoba was pointing to something much more fundamental — our role in the problem. Can we show up with authenticity and love to make an unselfish ask? Those are the necessary conditions of this love-science, and only when we’ve set ourselves up in that way do we earn the right to make conclusions on the efficacy of love in social justice.

In South Africa, more than four decades after Bhoodan was launched, apartheid had ended, and Nelson Mandela’s party was swept into power. There was a lot of fear amongst the whites who thought there would be retribution. Mandela shepherded his country away from revenge at this difficult time and toward reconciliation. This was not easy, for there were calls for justice. The path that South Africa took was remarkable. In the book, Wisdom of Compassion, Victor Chan and The Dalai Lama write of Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s response to a very difficult question, “How do you settle disputes without taking away people’s free will to choose forgiveness?” Tutu said that in the Truth and Reconciliation commission, set up to allow victims of human rights abuses to record their stories and acknowledge what they had been through, they would hear of heartrending abuse. And yet, after narrating the abuse, the individuals facing such abuse would frequently say they were ready to forgive. Many times, this would melt the heart of the perpetrators.

The Truth and Reconciliation commission was a unique experiment in restorative justice, and perhaps allowed the pent up fury of the victims of apartheid to be channeled into a space where they were listened to with deep love, a space where healing could happen. South Africa is by no means heaven on earth as far as racial tension is concerned. That its post-apartheid history has been largely peaceful is a testament to that country’s courageous choice of reconciliation over social justice. It remains one of the strongest economies in Africa.

The common thread between the Bhoodan project and the Truth and Reconciliation commission is the importance given to a whole perspective, respecting all involved while acknowledging injustice, and at the same time, owning our responsibility in the situation. Speaking at an event at Stanford on social movements, Prof. Ronald Howard, Director of the Stanford Decisions and Ethics Center highlighted this as he cautioned against any solicitation for campaigns of social justice. He noted, “..some of the most successful mass movements have been in directions that we now wish had never happened. For example, what happened in Nazi Germany or in Japan before World War II, and we can find many other situations where people really believed in what they were doing and yet they create all kinds of harm to themselves and others by doing it. … One of the problems when we make that opinion (of other people being evil) for ourselves is that we forget our part in the whole situation. .. In Shakespeare’s Hamlet, one of the characters says, ‘There’s nothing neither good nor bad, only thinking makes it so.’”

Howard’s caution is borne out by the tragic social justice movements in China, Zimbabwe and elsewhere. He suggests avoiding value-laden labels in our characterization of situations, especially loaded labels like “social justice” or “environmental justice,” which can easily be used to hide weak ideas that would otherwise not be palatable. This is sage advice, for it is consistent with the Buddha’s approach of combining a cool head with a warm heart.

It is also difficult to follow, for it implies going slower, and resisting temptations of quick glory. And yet, when followed, the consciousness of a whole people can shift, long after the movement has come and gone, as we see through the Bhoodan and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission experiences. True justice is about restitution, and victims cannot in the deepest sense be restituted as long as they have an identification with their victimhood, which can be long after external justice is served. The only hope for real restitution is the melting of hatred with unconditional love, for it is then that identities of both perpetrator and victim give way to a much deeper bond of co-evolution. A bond that surprises us with what’s possible.

Somik Raha holds a PhD in Decision Analysis from Stanford University and is Senior Associate @ Ulu Ventures, Volunteer @ ServiceSpace, Volunteer @ Society of Decision Professionals. You can follow his writings here: https://medium.com/@somikr

SHARE YOUR REFLECTION

3 Past Reflections

On Jun 18, 2018 Donna Willis wrote:

Thank you for bringing this topic into the conversation! I have been feeling strongly that we have reached the point in our society where we must bring the concept of restorative justice into our everyday lives. Now that we are peeling back the curtain to shine light on abusive behavior that had been considered 'just the way things are', we need to create a path toward reconciliation for those who have harmed others. If we just point fingers and demonize people, the wound will simply fester into hate and there are certainly enough angry people already! Thank you all for shining a light for us :)

1 reply: Cheryl | Post Your Reply

On Jun 18, 2018 Patrick Watters wrote:

"Be" love and justice. }:- ❤️

1 reply: Speedwell | Post Your Reply

On Jun 19, 2018 Maggie Spilner-Brotzman wrote:

So important to realize that deep transformation is an internal, not an external process---that Presence in and of itself -- is the most powerful healer and that without it, external process can fall into dissaray and unintended consequences...the quote: "Do you want to be right or do you want to be happy" comes to mind. If you justify your anger and hatred to enact change, you will only be adding to anger and hatred in the world.

Post Your Reply