Servant Leadership in Business: An Interview with Jose Juan Martinez

Interviewer’s note: I met José Juan in 2013. I had just returned to Spain from India and was participating in a 21-Day Kindness Challenge. During a 21 day period 5000 people from all over the world performed an act of kindness every day, totalling almost 11,000 transformative actions! The first day of the challenge I decided to buy a cake and gift it to someone random on the street. I wanted it to be anonymous so I needed to enlist a partner in kindness. The first person I met was José Juan! He gave away the cake and since then we have been connected in many adventures of service and generosity, including community experiments like Awakin Circles (which we started in his home after our chance meeting) or experiential retreats like Reloveution. José Juan is a permanent source of inspiration for those who meet him.

- Joserra G.

José Juan Martinez (JJ) is no stranger to success. An industrial engineer by training he built an impressive career at Bekaert, a multinational automobile company. But despite a string of professional accomplishments, when he hit 40, the predominant feeling he experienced was that of emptiness. Seeking to address this void he began an exploration of the world’s wisdom traditions that continues to this day -- and alongside his personal evolution he’s also built valuable bridges across geographies, cultures and fields of endeavor.

In this edited interview José Juan reflects on his remarkable journey and discusses everything from the crisis in our current leadership models, to how we can create space for empathy and collaboration in competitive environments.

Joserra (JR): Please share with us a little bit about your journey and its different experiments and learnings.

José Juan (JJ): Thank you! I have lived through quite an evolution in life. Since I got good marks in school I decided to study Engineering, maybe because that was the thing I was “supposed to do”. I didn’t choose Engineering as a vocation. My studies and my first jobs were all very heady, very technical. And after some time, in spite of my social and financial status, I felt like something was missing, I felt like there was a hole in my stomach… I didn’t know what to call it, but I was not happy. I ended up diagnosing myself as an emotional analphabet -- I was emotionally illiterate.

I have always been a curious man so I decided to do more research to better understand what was happening to me. I read somewhere that my symptoms matched what was called: “The Unhappy Successful Man Syndrome”. And this syndrome was so common that it had been catalogued. Many people around the world are working hard in big companies, climbing the ladder with a lot of sacrifice and dedication and when they arrive to the top of that ladder they realize they have put the ladder on the wrong wall. A strong sense of having been deceived comes over them.

For me, this happened when I was 40, and I am just happy it happened before I was 65. I’ve seen it happen to many people at that stage. People who retire and then feel completely empty. All their life they pursued one goal, one lifestyle, and one paradigm of success, and when they reach the top they realize the pursuit was an empty pursuit.

So at the age of 40, after feeling that emptiness, I started asking myself: What is my definition of a successful life?

The opportunity to think about this question came while I was working for Bekaert. Every year, the entire management team would go on a two day retreat to reflect on the mission, vision and values of the company, and define the strategy and the goals for next three years. In one of those retreats I had a great thought: The most important company in my life is me, so, why not hold this same kind of retreat for myself?

Every year, since 1991, I’ve spent two days by myself to reflect on my mission in life, and to face that great philosophical question: What is the purpose of my life? Is it money? Is it professional success? Is it something else? During these retreats I follow the same format we follow in our business retreats, only this time the company’s name is José Juan SA.

JR: And after some time you decided to share that personal process with more people...

JJ: Yes, while I was teaching in University, I shared it with my Engineering students and now, a few years later, they remember me not because of the theories I taught, but more because of the Self Leading process I shared with them. I realized this could be of great help for more people and since then we’ve been organizing three-day retreats where we explore intellectual intelligence with emotional intelligence and also body intelligence. In the companies I work with, people talk a lot about leadership and my premise for that is: How am I going to be able to lead others if I am not able to lead myself? I believe when you do some kind of personal work, then you are more fit to help others.

I am very passionate about this; I feel we have to teach these values, especially in school. I feel the leadership of teachers is essential and so is parental leadership; leadership understood as the capacity to influence others, something we all have. We can all influence our surroundings, our friends and family. But it’s important to have a our own self-knowing process first. For example, if parents can observe and reflect on how they were educated and generate insight from that, they will be able to do a better job with their kids.

JR: Do you think there is a leadership crisis right now in Spain and the world?

JJ: I think so. Not only in the political arena where it seems obvious, but also in many other fields: business, education, religion, organizations… I think we can tell when someone hasn’t done that personal work. Studies and our own wisdom tell us that all the great leaders in history went through some kind of self-knowing process, a process where they could discover their strengths, and discern potential areas of improvement. They were asking important questions. Questions like, “How can I be surrounded by people that complement me? How can I generate shared leadership, even when I am in the position of being the leader?”

At some Christian monasteries, like the one in Santo Domingo de Silos, they apply a very interesting model of leadership called “Saint Benedict's Rule”. It’s the rule that inspires the community at the Benedictine Monasteries and it was written by Saint Benedict 1500 years ago. For them, the Abbot is the boss, but there is a lot of participation and collective inquiry. The rule says: “At the monastery, whenever we have to talk about important matters, the Abbot will bring the whole community together and will personally expose the issue. Then he listens to all the brothers, after this he will reflect alone, and then decide what the appropriate action to take is. Do everything with advice from others and you will never regret anything.”

So in this case, the Abbot takes decisions, but he has listened to all the monks before that. He is a leader and he’s facilitated everyone’s participation. It’s a very interesting kind of leadership that has proved valid for more than 1500 years. I think current leaders should study these kinds of models.

JR: Sometimes you talk about Servant Leadership. I don’t know if you like the word “facilitator”. Personally I see a leader as a person who facilitates things for others, someone who makes things easier. I remember how in Bekaert, you had a very good experience in that sense, you found leaders who were always thinking about how to serve others.

JJ: Yes, I have realized the words 'leader' and 'leadership' have quite negative connotations for a lot of people, maybe because they are overused or maybe because they make them think about leaders they don’t like

I really like the idea of leaders as facilitators, and the idea that leaders are people who make the work of others easier, I think that’s the essence of what is called Authentic Leadership. In business people also talk of Situational Leadership. Sometimes there are very young teams that might require a more directive kind of leadership, but for me it’s true that the “great state of leadership” is Servant Leadership. In Bekaert, we used to say that the words that a leader should use most are: “What can I do for you?”. I practiced that and it’s amazing because those words have a deep meaning, they say something like: “I trust you, you know what you are doing, and I am here to help you”. In this way everyone in the company feels more empowered to use their own talent, and they feel more ownership over the organization and they feel more valued.

This type of leadership seems opposite to the hierarchal, pyramidal one, which is the traditional model that big companies are used to, very inspired by the leadership style of the Army, where one person is there to mandate, the other one to follow orders. When you tell someone: “What can I do for you?” they think, “What’s wrong with this person? Maybe he is a weak boss.” In China for example it’s hard for many people to understand this type of Servant Leadership, because they are used to a very hierarchical lifestyle. People act less on their own when they fear a mistake or a punishment. Many workers won’t move a finger unless it’s an order, and that limits their creativity and their talent.

I also realized that you cannot jump from one kind of leadership to another, you have to evolve progressively. As within people, so it is within organizations, there has to be a progressive evolutionary process. For some time I was frustrated in China because I tried to change the kind of leadership from one extreme to the other without considering their cultural background.

JR: A friend of mine Jayeshbhai Patel, director of the Gandhi Ashram in India often says, “Don’t be a Leader, be a Ladder”, meaning don’t take center stage, but instead be an instrument to help people rise to their potential and gain greater perspective for themselves.

JJ: Yes, I share the belief that the final mission of a leader is not to get more followers, but to create more leaders. I also like the expression Authentic Leadership. An Authentic Leader knows where to be in every moment, he is up front when things are not so good, and he is at the back when things are working. This is very different to what we see nowadays. There are many leaders who are unconsciously driven by their ego, people who have a great passion to be up front in photos.

JR: In this respect you talk about the 4 H’s that an authentic leader needs to develop…

JJ: Yes! It’s very fitting because the corresponding words in English also start with H. And in Spanish the ‘H’ has two interesting connotations, one is that it is silent, and in that sense, authentic leaders prefer listening to talking, and the other is the ‘H’ for ‘hacer’ (‘doing’ in Spanish), I feel an authentic leader is defined not by what he/she says but by what he/she does.

These are the 4 ‘H’s

- Honesty: Honesty comes first. A good leader has a base of honesty, not only integrity or lack of corruption, but also alignment between what he/she thinks, feels, says, and does. Honesty understood like this is the basis for trust, if you are not able to build trust, how are you going to be a good leader?

- Humility: Humility understood not as ‘thinking less of oneself’ but ‘thinking less about oneself’ and more about the people you work with. This kind of humility is very intertwined with the question: What can I do for you? The servant leadership approach is always testing your humility. Humility allows us to keep learning, growing and improving. The Japanese call it ‘Kaizen’. There is always room to improve. Who wants perfect leaders who know everything and never recognize their mistakes?

- Humanity: We are dealing with people not only things or projects. Authentic leadership has to do with methodologies but more importantly it understands emotions. An authentic leader has to have insight into human nature and be able to contemplate its four facets (physical, intellectual, emotional and spiritual). He/she has to be skillful in identifying and engaging other people’s talent, and also in helping people find their own gifts.

- Humor: A sense of humor can defuse a lot of tension. In these times, positivity is essential in our leaders. A leader who is always worried and who never smiles isn’t helpful. People now talk about emotional leadership as well. If the leader is in fear, then that extends to the rest of the team, and the same happens with their happiness and enthusiasm; emotions are contagious. The authentic leader needs to know and manage his/her emotions, because even though they are invisible, they are transmitted. It’s very easy to know when a leader is giving or taking energy from you, even if they don’t say or do anything.

In a Head, Heart, Hands retreat where we realized the 4 Hs form a great Ladder :)

In a Head, Heart, Hands retreat where we realized the 4 Hs form a great Ladder :)

JR: For me, a very interesting learning from a couple of the organizations I work with is the concept of holding space. The leader is a trustee of space for you so that you can grow integrally as a person. This is a kind of leadership that is fueled by a deep trust in others, an innate trust in their intelligence and wisdom. In some sense, it is a ‘Do Nothing’ style of leadership, where you lead simply by the example of your being, and hold space for others to explore their own gifts and talents in a safe space.

JJ: Yes, once I was asked: what is the quote that has inspired you the most in your professional life? I will always remember the words of my first boss in Bekaert, José Luis Martínez (someone who I respect a lot). We were in the middle of big changes and improving processes and he told us: “Out of every ten things we try, one is successful, so we have to try 100 things for 10 to work out. Try with no fear, and all mistakes can go to my account”. The only constraint he gave us was that our experiments couldn’t go against our basic values or principles. This created the kind of space that you talk about, where people can develop their creativity and talent.

There was full coherence between what he said and what he did. He was an example of humility, always wanting to learn, always studying new things and practicing what he learnt. This generated a culture in the organization that is still alive even now.

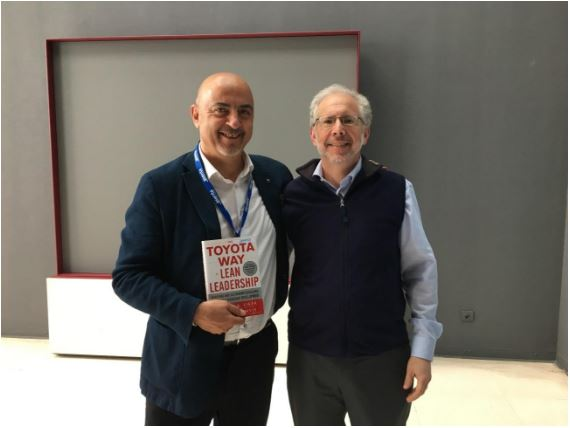

A few weeks ago, I was in Madrid at a course taught by Dr. Jeffrey Liker, someone who has been studying the Toyota’s Lean Manufacturing methods for 40 years, and there at the course was my former boss José Luis Martínez, 70 year old, still learning and improving!  With Jeffrey K. Liker in Madrid (June 2016)

With Jeffrey K. Liker in Madrid (June 2016)

JR: I also remember your work at Bekaert as Total Quality Manager, you traveled around the world and you started a project to implement a very holistic management model, you called it the Quality House, and that house was rooted in three fundamental principles that you distilled after research across factories and cultures…

JJ: Yes. Seven years ago, the president of our company changed. The new president saw that we were growing a lot in China and other Asian countries; we contracted more than 1000 new people every year. He saw that this model of growth was not sustainable. We started talking about Sustainable and Profitable Growth. It was profitable but we were not sure if it was sustainable. He used to compare it to a train track that is growing, but one of the rails is growing faster than the other; unless we balanced it, the train was going to derail. In that context of excessive growth, we decided to create a base of values that went beyond mere growth.

In this sense, we used to talk about 'development' as a better paradigm. Constant improvement or development doesn’t always mean growth. Today’s paradigm is: “If you don’t grow, you die”. Well, I am not totally sure about that, I prefer to think that if I don’t develop, then yes, I die. You can always develop, but you cannot always grow, because we are in a system with limited resources -- our world. One example I like to use to explain the difference between development and growth is the cemetery: cemeteries always grow, but they don’t develop. Development includes more intangibles like values, organizational consciousness, sustainability.

I and the new president of the organization fell in love at first sight. As a university professor, I used to explain Value Based Management to my students. I shared this approach with the president and we thought it could be a solution to ensure the system’s sustainable growth. The president then proposed that I elaborate a Value Based Management model to apply in 21 factories around the world.

To start with, we chose a representative from the different geographical areas with the idea of building a model together and then extending the work to the different factories. With that goal we chose a representative from United States, China, Turkey, Slovenia, Russia, Brazil and Belgium. It was a significant effort because every 15 days, we had to gather in Belgium for a couple of days. I started the process of trying to find the values that united us. What values unite Europeans, Americans, Chinese, Russian and Turkish people? I had a list of 140 values and I told them, “Let’s select the values that are common to all of us.” After various meetings and discussions we realized the process was not moving forward. The values we had were not transpersonal or trans-cultural values. It’s very different how every person and culture interprets them.

We were a bit lost but then I had the luck of a very important encounter in my life. I met Stephen Covey, who wrote the book 'The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People.' I went to a conference in Madrid and he was very sought after, but since I have not much hair like him, I think he liked me. He said to me, “We both go to the same hairdresser!” (laughs). José Juan with Stephen Covey

José Juan with Stephen Covey

I shared the trouble I was having in determining the common values across cultures, and he quickly replied: “Don’t work with values, work with principles. The difference between values and principles is that the values are individual, arguable and subjective. You can value fame, money, stillness… But principles are universal, they are intrinsic to human race; they are always there, acting, like the law of gravity.” Stephen said that there are a lot of values but not so many principles.

Another interesting fact regarding values and principles is that values run our actions; for example if I value fame or power or money, my actions will move accordingly, but principles act after action and determine the impact of our actions. If you do something without respect for another person then the consequences of that act will be out of your control. Stephen shares the example of Hitler. Maybe he had the value of family, maybe he was charming with his family, or treated his wife in a respectful way… But his actions didn’t follow the universal rules of respect, so then the consequences arise, consequences that are set by those principles. Values drive your actions and principles, the consequences.

With this message he gave me a very good clue. In the next meeting in Belgium I said: “Let’s see what are the great threats in the world today, what are the consequences of acting against the principles.” We tapped into what experts call: “The Great Threats”. One of the emergent themes was the inequity, within and across countries, another threat was terrorism, another the ecological crisis.

We all agreed that these were great threats, and according to Stephen Covey, these were the consequences we were experiencing in our world because we were not acting in accordance with universal principles. So then we said, if these are the consequences, what are the principles we are breaking with our actions? And we got three:

1. Solidarity: I am not alone in the world. Inequity comes from not understanding our fundamental interconnection. We talked about the famous subprime mortgages (with high risk), where people were thinking: “If I get the bonus for selling a mortgage, that’s good enough, I don’t care if you can pay it or not.” Our economical crisis arose largely from this kind of thinking.

2. Respect people: With terrorism and violence, there is a lack of respect towards the dignity of the people. You can be Christian, Muslim, Hindu, atheist, but I respect you regardless of your faith. You can be from one place or the other, you can be white or black, but I respect you. When we fall into intolerance, then we separate from others and the problem appears.

3. Care for the environment: The third principle we discovered was to care for the environment, for natural resources, for Nature. We totally depend on Nature to sustain our lives and we have forgotten this.

This process of discovering the principles as a group is one of the most amazing things that ever happened to me. A woman from China said: ‘Oh! These are the principles that Confucius used to talk about’. People coming from Christian and Muslim backgrounds said that it resonated a lot with their message of “Love one another”, people from Brazil connected it to the respect for Pachamama (Mother Earth for indigenous local cultures). We realized these principles were there at the root of all the great philosophies and traditions.

So we said, “This is it!” These are the pillars with which we want to build our house. The roof in China might be different from the roof in Spain, but the pillars will be the same. Then we had to share this with our bosses so we translated these universal principles into business language and we came up with the following:

1. Client orientation (stakeholders): Taking care of all stakeholders and finding the right balance between what give and what we get.

2. Respect people: Respect human dignity and contemplate all facets of human development: intellectual, physical, emotional and spiritual.

3. Elimination of waste: Use the least possible resources, only the necessary ones with maximum ecological efficiency.

These were three pillars of the house that were not going to change. The bricks might change, the roof might change, but the pillars would remain the same. After those pillars, above them, we located all the systems of the organization, and all the action procedures. In the end, our principles helped evaluate all our functions.

For example, if I had a selection process and was not giving equal opportunity to all aspirants, then I wasn’t truly respecting people. I had to make sure my procedures aligned with our principles, and also ensure that there was no favoritism. Another example, if I take three weeks to choose someone instead of five weeks that would be better.

A typical mistake in Value Based Management is that all companies talk about it, but they end up doing nothing to implement it. I led a study on values and principles followed by international companies. All of them talk about respect, and stakeholder orientation. But how do they apply these values? All companies like to systematize actions into procedures and protocols. These protocols can be evaluated to see if they follow the principles, if they don’t, I know the consequences will be negative. I ask myself, how many companies would pass that test?

Our Quality House in Bekaert

Our Quality House in Bekaert

When someone new entered the company, he was introduced to the organization through the Quality House. We also used the model to justify our goals. For example if our main goal was not to have work accidents, that was aligned with our core principle of respecting people, and when we said we wanted to reduce the use of resources, that was aligned with the elimination of waste.

At a practical level, every year we would evaluate goals, results and systems in a very simple way, and that allowed us to find improvement areas and good practices in the different factories and departments. This process was similar to those applied by different companies like the EFQM model (European Foundation of Quality Management), the Malcolm Baldrige Excellence Model used in United States, and the Deming Prize used in Japan. One difference with our model is that we would evaluate behaviors as well, which is quite innovative. We had a list of behaviours that were aligned and misaligned with the principles (Do’s and Dont’s) and we would ask our workers: How far are we from our principles? We would analyze the results and then take action.

The 4 years I spent working with the Quality House all over the world were great. Talking about such things generated a very deep communication between us, no matter if we were Chinese or Spanish, this was something that connected all of us; those principles are part of the essence of being human and transcend our cultures and personalities…

JR: I feel we haven’t designed according to such principles. Companies act many times against those principles, against what makes us feel happy, connected.

JJ: In companies, people sense it. As you know, in companies we talk about mission, vision and values. Sometimes with values we try to apply them, we work with them, but many times they don’t become part of reality. There is a separation… We come back to that half meter problem, the distance between the head and the heart. Japanese people always say, look to the feet not to the mouth. The feet are what you do, how you move. What you say is not always aligned with what you do. This is why I feel Authentic Leadership and Laddership are so important. I have seen that working with the organization and forgetting the individual is very complicated. If you haven’t worked with your own leadership, within your own life, you are going to be very limited when leading others.

Joserra G. is a service-hearted generosity entrepreneur, meditator, and activist for the common good. With his witty humor and kind heart, Joserra has a profound ability to connect with just about anyone he meets. He is also the founder of "ReLoveUtion" -- a renaissance of compassionate societies.

On Sep 3, 2018 deborah j barnes wrote:

All very nice, really, however that which is truly of value can be re-envisioned as a transitional path, to satisfy the number games that have absurdly taken hold of our species and set new direction. Those first priest/scribes impressed the big honcho, the self designated god/king or super shaman and a new buffer zone (H Zinn) was carved out and claimed. Now way back in the day organizing groups in this classic animal set up made sense. However as consciousness and ego grew it became as trapped; limited by its own social power creation. Now it has a complex and intricate set of systems all working to a world that sees success in countable monetary terms via participation in that elaborate, rusty, creaky thing designed to launch the primitive awakening ego ego. Pushing self up by smashing another down set off ta testosterone rush and helped alleviate fear. However an ego constantly comparing, competing and gorging off others will never realize it's greater potential. Its like looking in a mirror and seeing only the reflection. It is time to move on!

[Hide Full Comment]Post Your Reply