The Boy Who Wanted to Go to School

Wubetu Shimelash (’20) is kneeling on a dirt floor near an open doorway where a plastic bottle filled with holy water is suspended by a string to bless all who enter this home in the Ethiopian highlands.

Because Wubetu is here, the four children of this house are especially blessed today. Their mother, Wubetu’s friend Abeju Messele, is tending a fire in the corner. She crushes coffee beans with a long pestle to prepare coffee for guests, an ancient and ongoing ritual of hospitality in Ethiopia. The smoke mixes with the fragrance of coffee beans to fill the room, cold and damp during these rainy months, leaving children with perpetually runny noses and shoulders wrapped in blankets.

Wubetu and the children form dark silhouettes as a soft light flecked with mist illuminates the Simien Mountains through the doorway. Outside, chickens cluck and scratch. Inside, on the floor with the children, Wubetu quietly examines a laminated poster. He begins pointing to letters, urging children to show him their best efforts — a recitation of the alphabet — first in their native Amharic and then in English.

He will repeat a version of this scene over a week throughout stops in his native Ethiopia. Children flock to him wherever he goes, drawn to this 23-year-old man wearing a black, signature fedora, his pockets full of candy, his smile radiating acceptance of anyone who cares to share a few moments with him, better yet a dance. “Never pass up an opportunity to change a stranger into a friend,” he likes to say. Every chance he gets, he asks children whether they are going to school, where they rank in class and whether they know their alphabet.

Education, after all, has meant opportunity for Wubetu Shimelash. It is unsurprising that among his few material treasures is a worn paperback, “Never Pass Up an Opportunity: 51 Opportunities for Improving Your Life,” by Larry Czerwonka. “Passing up an opportunity without trying it is my biggest fear,” he says.

Even if others cannot follow him from his beloved rocky spires, canyons and waterfalls to the United States, or to Wake Forest, Wubetu believes in the power of education to change lives. It changed his.

.jpg)

Wubetu was born in the village of Argin, nearly two hours by very slow mule ride from Abeju’s house near Chenek Lodge in the Simien Mountains National Park. His birthplace was a round hut of mud with a grass roof and walls sealed with animal dung. In recent years it has been replaced with a rectangular house made of eucalyptus poles and stones, but the floor and the walls are still dirt, and the mules still shelter inside, beneath the loft where Wubetu’s siblings and parents sleep.

On this July day, his mother, Aschila Endalsasa (P ’20), goes to a back room to retrieve an object in the shape of a tractor seat. It is a disk made of dirt and animal dung. Someone has spread long strands of grass on the dirt floor in her absence. This is the kind of “seat” on which Aschila gave birth to Wubetu and his five brothers and three sisters.

“Push! Push!” villagers shouted to encourage her.

“Push! Push!” Wubetu, the second born, cried when he was old enough to join them outside the house to cheer for his siblings’ births.

Grandma Lemlem Ambawu, Wubetu’s paternal grandmother, toothless, smiling and regal in garb that signifies her position as an elderly spiritual leader in the community’s Ethiopian Orthodox Church, was present for Wubetu’s birth, and she named him.

Wubetu. He who brings joy and happiness. And handsome.

Wubetu Shimelash ('20) was born the second of nine children in Argin, a village in the highlands of Ethiopia.

Wubetu Shimelash ('20) was born the second of nine children in Argin, a village in the highlands of Ethiopia.

He was born in 1995 at an auspicious time — Jan. 7 — Ethiopian Christmas and the occasion of a bountiful barley harvest. From the start, the bond between Grandma Lemlem and Wubetu proved immutable, in some ways forming the first strands of a web of unseen hope stretching to the United States.

Even when 4-year-old Wubetu killed a chicken by trying to ride it like a horse with a stick as a saddle, Grandma Lemlem stepped in on his behalf to confront his parents. “This is my boy. This is Wubetu. You can’t do that,” she says, recalling — thanks to Wubetu’s translating — how she made sure Wubetu could avoid a parental thrashing over the dead chicken. She laughs about it to this day. “Even though you killed it, I loved you being adventurous.”

“I guess she’s a little biased towards me,” Wubetu has admitted. “She just loves my enthusiasm. She loves hanging out with me.”

Wubetu greets Grandma Lemlem, whom he calls his "secret sauce" and "the happiest person I've ever known," at his family's home in Argin, Ethiopia, in July.

During his childhood, Wubetu followed the path of boys in his village. At 6 he became a herder of his family’s livestock — 200 sheep and a fluctuating number of goats, horses, cows and oxen. He tended them in this spectacular land of desert-style trees, Ethiopian wolves, gelada baboons with fur like lions’ manes and mountain peaks that rise well above 10,000 feet. Here, Wubetu wrapped himself in a sheepskin for warmth, clasped his bull whip, secured his daily ration of barley snack and traversed the mountains in search of the best spots for grazing. Many nights when they were far from home, he and other shepherds sought shelter with the animals in caves and started fires by rubbing rocks together. He can point in the distance to his favorite caves, high above the river, high above the only civilization he knew — Argin.

For years, herding was his life. In his village that was enough. Girls help at home, wash clothes in the river and fetch water and firewood. Boys tend sheep until they are old enough to plow and work the fields. Girls and boys grow up to marry in communal celebrations that feature home-brewed beer and a feast of slaughtered sheep or goats. It’s a life of subsistence farming without running water, bathrooms or electricity and scant ambitions beyond the village — with reason. Wubetu was warned, as all children were warned, never to think about leaving the village and setting out for a city. Cities were filled with cannibals, cautioned the elders, and cannibals ate children from the countryside.

The elders, however, could not stop city folk from coming to them. Nor by economic necessity would they want to. Tourists long have found their way to the Simien Mountains National Park, since 1978 a UNESCO World Heritage site. They hike, camp and scan rocky outcrops for a glimpse of the walia ibex, an endangered wild mountain goat.

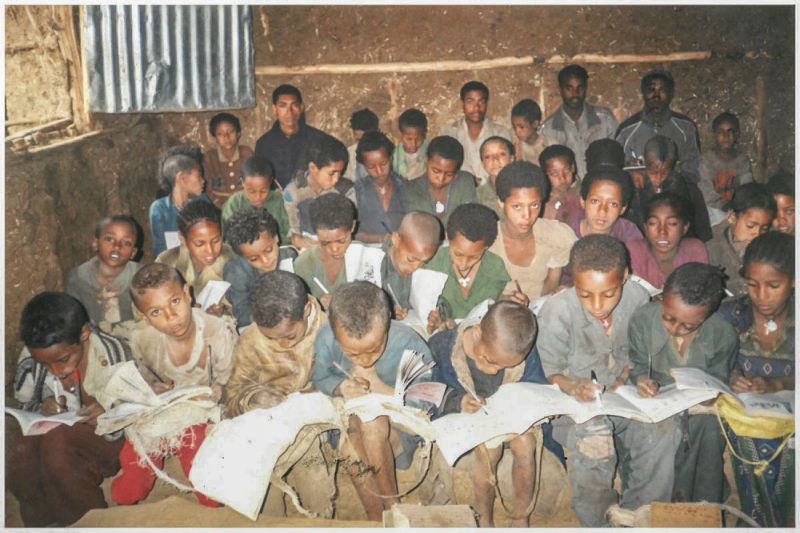

Children gather at the doorway of the school in Ambaras, Ethiopia. Wubetu walked five-hour roundtrips to attend this school.

Children gather at the doorway of the school in Ambaras, Ethiopia. Wubetu walked five-hour roundtrips to attend this school.

Wubetu, third from right on the front row, began his quest for education in this school in Argin.

When he wasn’t plowing, Wubetu’s father, Marew Shimelash (P ’20), would find work as a porter for tourists. During his childhood, whenever he could, Wubetu would jump at the chance to substitute for his father, running alongside tourists to carry their bags or supplies, offering to rent them one of his horses, hoping to pick up tips and a few English words. He displayed his first signs of entrepreneurial zeal in this role. He coaxed truck drivers into selling him drinks that he would turn around and sell to tourists at higher prices. He crafted striped hats from sheep’s wool, sometimes earning the equivalent of pennies for weeks of handiwork for one hat, sometimes earning five dollars. Whenever he could, he collected scraps of newspapers and studied them. Sometimes he asked tourists or tour guides to explain words to him. That’s how he taught himself to read and speak a bit of English.

That’s also when the yearning grew. He desperately wanted to go to school, a 30-minute walk from his house. Mostly school was held under a tree, but students eventually moved into a one-room wooden building with a metal roof and dirt mounds for seats. Wubetu’s parents had let Wubetu’s older brother attend school in another village because they hoped he might become a priest. School was not for Wubetu. Taking care of animals and farm life were more important than education, his mother told him.

A dead sheep changed things. When an Ethiopian wolf attacked and killed one of the flock, Wubetu was afraid to tell his family. He hid. Villagers searched for him but didn’t notice when he climbed up the side of his house and snuck into the sleeping loft through an opening. Hidden away, he could hear his parents express their worry. He heard his father say that he would let Wubetu go to school if only he would return safely. That’s how Wubetu won the school argument.

Wubetu's father, Marew Shimelash (P '20), works occasionally as a scout in the Simien Mountains National Park.

Wubetu's father, Marew Shimelash (P '20), works occasionally as a scout in the Simien Mountains National Park.

Wubetu's mother, Aschila Endalsasa (P '20), foreground, hosts a coffee ceremony in the family's home for Grandma Lemlem, second from front.

Wubetu's mother, Aschila Endalsasa (P '20), foreground, hosts a coffee ceremony in the family's home for Grandma Lemlem, second from front.

Soon at his local school, he was skipping grades and winning first-in-class certificates. With few supplies and nowhere nearby to buy them, he burned sticks to create a “charcoal” tip and write his lessons on rocks and leaves. He wrote math problems on the sheer rock faces of the mountains and reviewed the scrawled equations on his way to school the next day. Soon, though, there was another problem. He had completed the last grade the school offered, and he wanted more.

His only option was a school in the village of Ambaras. Even for a sure-footed and fast runner like Wubetu, it would be a five-hour round trip. Negotiations again ensued. Could Wubetu juggle chores and schooling that far away? Sometimes he would rise at 4 a.m. to help his father before hiking to school. Sometimes he would stay up late into the night studying by the light of a candle. He kept his feet in a pan of cold water to stay awake.

One of the few days he remembers crying was after a team competition in Argin school. “The stakes were high,” he says. A girl on his team forgot the answers, and Wubetu’s team lost. Regretting the prizes that got away and hating to lose, he says, “I wanted those pencils and paper.”

Wubetu has fashioned sandals from old tire rubber and keeps these in his dorm room at Wake Forest.

Wubetu has fashioned sandals from old tire rubber and keeps these in his dorm room at Wake Forest.

A young Wubetu, left, plays soccer with a ball he made of old clothes. He invited the tourist to join the game on that life-changing day in 2009.

A young Wubetu, left, plays soccer with a ball he made of old clothes. He invited the tourist to join the game on that life-changing day in 2009.

Most school days were happy ones. That was the case in fall 2009 when a group of tourists visited a nearby water project and the school in Ambaras. Wubetu, 14 at the time but barely looking 9, was playing soccer with his friends with a ball he made from old clothes. He noticed a tall, blue-eyed man watching the game. It was clear he wanted to play. Wubetu made him wait for a while. (“I made the ball. I made the rules,” he recalls with a grin.) Then Wubetu kicked him the ball. The man kicked it back. Wubetu returned the kick. And the man was in the game.

A photograph from that day — the day Wubetu’s world opened beyond Argin, beyond Ambaras, beyond the region of Amhara and beyond Ethiopia — shows a jubilant white man wearing a colorful scarf and running across the field among the boys. Wubetu is in the picture, an equally jubilant sidekick.

When it was time for the man to rejoin his group, Wubetu tagged along. He was eager to practice his English and ask questions. He figures the walk lasted about 30 minutes and ended with an offer from the man:

“If you need help with your education, you can reach out to me.”

Then the man handed him his business card and $30 for what he hoped would pay for a jacket. And then the man was gone, leaving Wubetu “feeling like the billionaire in Ethiopia.” Into one pants pocket went the $30 and into the other — the one with the hole — went the business card with “its random letters and numbers.”

Wubetu demonstrates in Debark, Ethiopia, in July how he and fellow shepherds competed by cracking their bullwhips.

Wubetu demonstrates in Debark, Ethiopia, in July how he and fellow shepherds competed by cracking their bullwhips.

Before long, Wubetu had a shopping list for someone traveling to the nearest town and back. The $30 bought Wubetu his first jacket, an English grammar book and his first pair of real shoes — sneakers — to replace the sandals he had fashioned from old tire rubber.

Months went by until the mind-blowing day Wubetu recalls vividly. He was running when he saw a friend in the mountains, a friend who was quickly impressed.

“What do you got there? Which tourists give it to you?”

“I bought them myself,” Wubetu recalls saying proudly, basking in admiration for his new shoes. “A man gave me the money.”

Wubetu reached into his pocket, the one with the hole, and fished out the business card. He showed it to his friend, who said, “There is email on here! And actually, you can email.”

Wubetu had one reply to his friend: “What’s an email?”

The friend further advised him: “There is a thing called a computer that looks like this: it has a rectangle and the back is long. It has a keyboard and you press the letters. You type it there — the message — and it will pop out in the U.S.”

His friend told him they could go to an internet café to find such a thing. There was one in Debark, the town nearest the entrance to the national park. “I had no idea what he is talking about,” Wubetu says. But together he and his friend hatched a plan. Though they would make the trip separately, they would journey to Debark to use the machine.

Wubetu takes his old seat in his school at Ambaras, in what he calls "a fine building" that he praised for having had books.

Wubetu takes his old seat in his school at Ambaras, in what he calls "a fine building" that he praised for having had books.

In July, a woman roasts coffee at Unforgotten Faces, a nonprofit that supports parents and disadvantaged children about an hour from Ethiopia's capital of Addis Ababa. Wubetu volunteers there whenever he can.

In July, a woman roasts coffee at Unforgotten Faces, a nonprofit that supports parents and disadvantaged children about an hour from Ethiopia's capital of Addis Ababa. Wubetu volunteers there whenever he can.

A red dirt road winds through the mountain near a steep drop off that descends into Wubetu’s village and its valley. This is the road to Debark that Wubetu took, along with shortcuts through valleys and mountain passes, but always within sight of the red dirt road, the only route he trusted to find his way to Debark.

He walked and walked and walked.

“I walked with the hope,” Wubetu says.

His journey took 12 hours. When Wubetu arrived in Debark he asked around and found his friend. Together they went to the internet café. The power was out, which is a common occurrence in Ethiopia. But how would a boy without electricity know not to stress about power outages? There was no way to discover the magic of the computer until the next day. Wubetu was angry, an emotional state few who know him can imagine because of the joy befitting his name.

By this time his family had moved to a house in Debark. They had left Wubetu in the mountains to go to school and tend to the animals. He had never been to Debark or seen his family’s house in town. That’s where he stayed for a few days.

With the power back on at the internet café, Wubetu was ready to try the machine but needed coaching by the internet café worker. Wubetu wrote a short message in Amharic, then translated it as best he could into English to be typed into the computer. He can’t remember the exact words, but they proclaimed he was Wubetu from the soccer game and would like help with his education. Do you remember me?

For at least a day, there was no answer. Wubetu had his doubts that any answer would come, and if it did, how did he know it wasn’t someone in a back room of the internet café tricking him?

Wubetu visits Abba Teka, an elderly spiritual leader in Debark, Ethiopia, and slips him a few bills. "I feel like I'm rich," Wubetu says. "I don't have the money in my pocket, but I have a lot of people who love me and people I love."

Wubetu visits Abba Teka, an elderly spiritual leader in Debark, Ethiopia, and slips him a few bills. "I feel like I'm rich," Wubetu says. "I don't have the money in my pocket, but I have a lot of people who love me and people I love."

The man in the United States remembers getting the message — “really short and sweet” —and his private response. “Holy s …! Wow! This is amazing.” Sure, he remembered Wubetu. The boy’s email was a shock and needed a response.

He emailed his employee in Addis Ababa and copied Wubetu: “You guys connect.” The deal was that his employee and friend in Addis would find a local school in Addis to enroll Wubetu and make sure the plan had the blessing of Wubetu’s parents.

That September or October day in Ambaras, the man had given the $30 and doubted he would hear from Wubetu again, but “I left with joy that I got to meet such an interesting young man. It just gave me hope for kids and education across the world.”

The man had years of experience traveling, having visited some of the world’s poorest places, having competed with his sister on “The Amazing Race” television show, having lived experiences that would eventually inspire his 2011 best-selling book, “Start Something That Matters.” He is Blake Mycoskie, founder of TOMS Shoes and one of the most famous social entrepreneurs in the world. He created the One for One business model: for every pair of shoes sold, a pair is donated to a person in need. (Now the company also provides products or services such as prescription eyeglasses, obstetric supplies and clean water for communities in need.)

Blake Mycoskie celebrates Wubetu's high school graduation at Scattergood Friends School & Farm in West Branch, Iowa, in 2016.

Blake Mycoskie celebrates Wubetu's high school graduation at Scattergood Friends School & Farm in West Branch, Iowa, in 2016.

Blake says Wubetu was — and remains — the only child on the planet to whom he has given his business card.

“I find him to be incredibly curious and incredibly positive,” Blake says. “I feel like those are the two characteristics that people have always said about me as well, and so it’s something that I think has really allowed me to see myself as a young man in him. … I think there’s a lot to be said for just sheer optimism and positivity in all situations and the belief that you can do anything if you’re given the opportunity.”

Blake’s friend and colleague would provide “boots on the ground” to find a school for Wubetu, while Blake would cover expenses. But, once again, a big question arose: How would Wubetu win his family’s permission to go to school in the capital, traveling to the land of cannibals?

Wubetu did what he does in Ethiopia (and on campus). He found a quiet spot in nature. On his favorite mountaintop in Ethiopia, he meditated about cannibals and Blake’s offer. “My mind is divided. Do I trust my community, my dad, my mom, my family and the people I grow up with who cares about me and loves me? Or do I trust random tourists and tour guides?” They had told him not to believe the lie about cannibals.

His answer came as he was writing a poem. “And at the end I make a decision. All right. This is an opportunity I’m not going to pass.”

He decided to go down from the mountain and turn to Grandma Lemlem, “my secret sauce.” Win her permission first, he figured, and the rest would follow. “Nobody says no to my grandma.”

He went to her house, gave her a kiss, “cuddled with her a little bit” and helped her clean her backyard. Buttering her up worked. He convinced her that his going to school in Addis was going to be great. To which she responded, “If you say so, Wubetu. You know me.”

It wasn’t easy for Wubetu to persuade his parents, but, with the help of Grandma Lemlem, eventually he did. His father decided to ride the bus with him the two days’ trip from Debark. Weeping inconsolably, his mother grabbed the bus door and wouldn’t let go. It marked Wubetu’s toughest decision: “I’m punishing my mom and going to a dream that I don’t even know what it is.”

Wubetu’s father made his only trip to date to Addis Ababa. He remembers how the pair stopped on the way. Wubetu saw the country’s biggest lake, Lake Tana, on the bus trip and the ruins of famous 17th century royal palaces. At least I have seen these places, his father remembers Wubetu saying. “It is good enough for me whatever the future,” Wubetu told him, “even if my next path doesn’t work.”

“I knew he could handle the challenge,” Wubetu’s father says.

And Wubetu did. He lived with Blake’s friend, mastering shower knobs for hot and cold water and TV remote controls. He spent three years in school in Addis. About a year after Wubetu had been in school, Blake went to Ethiopia to visit him. Wubetu showed him his report cards and his “great grades.” “One of the things I didn’t realize until he showed me the report cards was the name of the school was School of Tomorrow. The name of TOMS came from Shoes for Tomorrow, and (then) Tomorrow’s Shoes, and Tomorrow was just too long, so we shortened it to TOMS.”

The instant when it registered that Wubetu was at the School of Tomorrow still leaves Blake dazzled. “It just was this moment in life when you feel — regardless of your religious belief, or God or a higher power — kind of telling you, ‘You’re doing the right thing.’ That was one of those moments in my life that I’ll never forget.”

And it foretold an even deeper bond. “I refer to him as my son all the time and very rarely do I ever distinguish between him and my biological kids,” Blake says. “He’s brought so much joy to me and my wife (Heather), my friends, my parents. I see him as a son, and I feel we will be connected for as long as we’re on this planet and that we were meant to be together.”

Blake financed Wubetu’s education two years at the School of Tomorrow and a year at another Addis private school. Wubetu surpassed all expectations and overcame the ostracizing he faced at the beginning, when students bullied him with the nickname “farm boy.” He worked harder and longer, earning 14 first-in-class certificates at the School of Tomorrow.

He says: “Nobody was beating me in school because the five hours that I was investing in the walk to school now I’m investing that on studying. The times that I was investing to help my dad with the farm, I’m investing that on school. I was unstoppable.”

His next step was the United States. He pointed once to the sky to show his mother how he could make the trip. An airplane flew overhead. “How does a big man like you fit in that small bird-looking creature?” she asked. He later showed her how with a video on his cellphone. One question always leads to another. How, she asked, does the phone “capture a big picture like a plane?”

Wubetu spent 2013-2016 in West Branch, Iowa, completing high school at Scattergood Friends School & Farm. The Quaker college preparatory school sits on 126 rural acres and includes farming experiences for the students. Wubetu was given charge of a lamb. He named it Tom and trained it like a puppy.

He distinguished himself at Scattergood, serving on a team recognized for a video game creation — the only game lacking violence — and winning an Excellence in Education award from the Iowa City Area Chamber of Commerce in 2015. Louis Herbst, Scattergood’s dean, writing in the school’s newsletter about outstanding “Scattergoodians,” as they are called, said, “Wubetu has worked harder than any student I have seen in 10 years of teaching. With his insatiable curiosity, Wubetu takes every opportunity to learn.” That year Wubetu also received his school’s Berquist Award recognizing a student who excels as a community member: “We look for a student who brings positive energy, a volunteering spirit, and integrity to our campus.”

Wubetu has coached the children on the alphabet at the nonprofit Unforgotten Faces, and now it's time to play.

Wubetu has coached the children on the alphabet at the nonprofit Unforgotten Faces, and now it's time to play.

With a record like that, Wubetu figured he remained unstoppable. He was sure he would get into Harvard, his first choice for college. Now skilled at computers, he searched the internet and came across Wake Forest. He liked what he read, and he especially liked the green spaces. He decided to apply there, too.

He remembers the mail arriving. Harvard rejected him. “Whereas,” as he puts it, “Wake Forest says, ‘Oh, we’d love to have you!’”

As so many accepted students did in April 2016, he visited campus and met staff and students, including international students. He went to Reynolda Village and its woods, “which is an amazing forest,” and found a peaceful place to meditate, pray and find quiet. “I was being welcomed very well. I just loved the community well. At that moment, I decided this is the place to go,” he says.

His Instagram post on April 23, 2016, will seem familiar to any young Wake Forester. Along with video of the visit, including a shot of him with the Demon Deacon, Wubetu announces, “Officially #demondeacons #wfu20.” He wrote about how much fun he had with African students and others “while enjoying the fresh air at @wfuniversity.”

His first two years at Wake Forest brought lessons in time management; he joined 20 organizations as a freshman and hardly got any sleep. He learned how to apply and win a Richter Scholarship to fund a film in Ethiopia; he made it in summer 2017. He learned how to apply to spend his junior fall at Worrell House in London; he was accepted. He learned he is destined to be an entrepreneur. (Already he has started Simien Eco Trek with a childhood friend to arrange travel in Ethiopia, so visitors can enjoy his country’s natural beauty and culture.) He learned that he also is destined to be a filmmaker, perhaps combining both business and filmmaking. (His major is communication; his minors are film studies and entrepreneurship.) He learned that living in Magnolia Residence Hall is “like living in a hotel.” He learned some students think walking across campus is a long way — and tiring. But he doesn’t fault them. He knows their experiences growing up were different from his. Thanks to his popularity, he learned to pad every walk to Reynolda Gardens for jogging or meditating by an extra 20 minutes, so he can talk with people along the way. He learned professors appreciate that he takes them up on office hours and meetings at coffee shops even though he doesn’t drink coffee; he is genuinely interested in them and has lots of questions.

His parents are proud now of his education and hope other children will follow. His younger brother has been accepted to Scattergood and will attend if a U.S. visa comes through. His parents say they want Wubetu to help them and the community financially and be a role model for other children.

Blake, who has been Wubetu’s financial benefactor since Wubetu started school in Addis, says, “I’ve never seen a greater return on an investment. Not just how much he’s thriving but how many people he’s inspiring and impressing every day.” He hopes Wubetu won’t overextend himself or put too much pressure on himself. Aside from those aspirations, he hopes Wubetu “can use his amazing charisma and drive and unique set of skills to help others.”

For himself, he says, “My son’s only 3 now, but my prayer is that I have the same connection with my biological son that I have with Wubetu.”

***

“Wherever I go, I am not lost,” Wubetu says. “I go with my values. I try to adapt to a new culture without losing my culture.”

His values? Being happy. Being kind. Staying positive. Working hard. And loving. “The power of love is limitless,” he says.

The power of love has not wavered — for his family, for his country, for Wake Forest friends, for Blake and his family who host him during school holidays on ski trips in winter or whenever they can at their home near Los Angeles.

In his home country, Wubetu is known in the highlands to leap out of a parked car and onto a rock to spread his arms wide and shout, “Welcome to Ethiopia!” He wants his friend to film him whenever he can, so he can post videos on social media or share the images with his U.S. friends. He wants them to know why he loves his country.

During this week in July, he has made that leap from the car several times. At one spot, near the first school he attended, in Argin, he points to a mountain in the distance. Weather is closing in, with a chilly fog inching up the slope.

“See that path to the clouds?” Wubetu asks. “That’s the path I used to walk.”

Those who know him would say, without a doubt, he still does.

Syndicated from Wake Forest Magazine. Photography by Ken Bennett on campus and Maria Henson ('82) in Ethiopia

SHARE YOUR REFLECTION

4 Past Reflections

On Nov 13, 2018 Virginia Reeves wrote:

This young man and all those who've supported him deserve a round of applause. He has clearly demonstrated that taking advantage of an opportunity, being determined, and sharing hope and goodwill lead a person to a life being lived well.

On Nov 13, 2018 Kristin Pedemonti wrote:

What a deeply inspiring read, thank you for the details, I could feel, see, hear, smell all the images shared oh Wubetu, I wish you well on your joyful journey! Here's to the amazing way the universe responds when we reach out as you did with no fear! <3 HUGs from my heart to yours!

On Nov 13, 2018 Patrick Watters wrote:

Beautiful and continuing story! If we are looking and listening carefully we will be aware of the foundation of Divine LOVE beneath it all (God by any other name). We don’t necessarily need to use words to acknowledge the Divine, especially when our life and experiences are constantly pointing to it - like fingers pointing at the moon. }:- ❤️ anonemoose monk

On Nov 14, 2018 Sidonie Foadey wrote:

Simply beautiful! Such an inspiring and empowering life experience! Kudos to you, Wubetu, and your loving friends. Love & blessings.

Post Your Reply