Against Self-Righteousness

Few things in life are more seductive than the artificial sweetness of being capital-R Right — of “winning the narrative,” as my friend Amanda likes to say. This delicious doom and glory of being Right — which is, of course, a matter of feeling rather than being it — tends to involve framing our emotional triggers as moral motives, then thundering them upon those we cast in the role of the Wrong, who may do the same in turn.

How, amid this ping-pong of righteousness grenades, do we maintain not only a clear-minded and pure-hearted relationship with reality, but also forgiveness and respect for others, which presuppose self-forgiveness and self-respect — the key to unlatching the essential capacity for joy that makes life worth living?

That is what the wise and wonderful Anne Lamott considers with uncommon self-awareness and generosity of insight throughout Almost Everything: Notes on Hope (public library) — the small, enormously soul-salving book that gave us Lamott on love, despair, and our capacity for change.

Lamott writes:

When we are stuck in our convictions and personas, we enter into the disease of having good ideas and being right… We think we have a lock on truth, with our burnished surfaces and articulation, but the bigger we pump ourselves up, the easier we are to prick with a pin. And the bigger we get, the harder it is to see the earth under our feet.

We all know the horror of having been Right with a capital R, feeling the surge of a cause, whether in politics or custody disputes. This rightness is so hot and steamy and exciting, until the inevitable rug gets pulled out from under us. Then we get to see that we almost never really know what is true, except what everybody else knows: that sometimes we’re all really lonely, and hollow, and stripped down to our most naked human selves.

It is the worst thing on earth, this truth about how little truth we know. I hate and resent it. And yet it is where new life rises from.

To let go of the tightly held convictions that keep us small, separate, and severed from the richness of life is to let the ego — the gallows on which our beliefs and identity hang — dissolve into an awareness of shared being, or what the poet Diane Ackerman called “the ricochet wonder of it all: the plain everythingness of everything, in cahoots with the everythingness of everything else.” Half a century after Bertrand Russell asserted that the key to growing old contentedly is to “make your interests gradually wider and more impersonal, until bit by bit the walls of the ego recede, and your life becomes increasingly merged in the universal life,” Lamott writes:

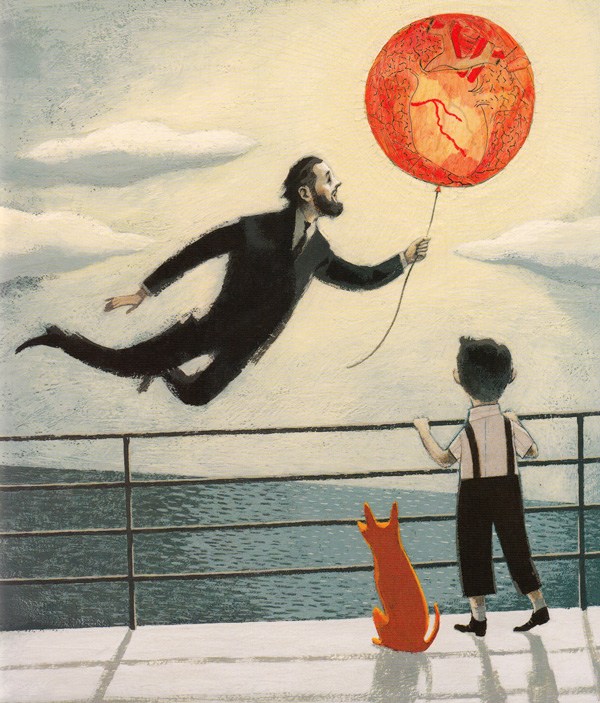

What comforts us is that, after we make ourselves crazy enough, we can let go inch by inch into just being here; every so often, briefly. There is flow everywhere in nature — glaciers are just rivers that are moving really, really slowly — so how could there not be flow in each of us? Or at least in most of us? When we detach or are detached by tragedy or choice from the tendrils of identity, unexpected elements feed us. There is weird food in the flow, like the wiggly bits that birds watch for in tidal channels. Protein and greens are obvious food, but so is buoyancy, when we don’t feel as mired in the silt of despair.

From this recognition of the shared flow of existence — the wellspring of what the poet Lucille Clifton called “the bond of live things everywhere” — arises a calm universal compassion, which becomes the mightiest antidote to self-righteousness. Lamott writes:

Almost everyone is screwed up, broken, clingy, scared, and yet designed for joy. Even (or especially) people who seem to have it more or less together are more like the rest of us than you would believe. I try not to compare my insides to their outsides, because this makes me much worse than I already am, and if I get to know them, they turn out to have plenty of irritability and shadow of their own. Besides, those few people who aren’t a mess are probably good for about twenty minutes of dinner conversation.

This is good news, that almost everyone is petty, narcissistic, secretly insecure, and in it for themselves, because a few of the funny ones may actually long to be friends with you and me. They can be real with us, the greatest relief.

As we develop love, appreciation, and forgiveness for others over time, we may accidentally develop those things toward ourselves, too.

Only by coming to terms with our own brokenness, Lamott suggests, can we build from the pieces a temple of joy — a state of being that is almost countercultural today, one which Lamott defines as “a slightly giddy appreciation, an inquisitive stirring, as when you see the first crocuses, the earliest struggling, stunted emergence of color in late winter, cream or gold against the tans and browns.” With an eye to the miracle of joy in a world so imperfect and strewn with suffering, she writes:

This is how most of us are — stripped down to the bone, living along a thin sliver of what we can bear and control, until life or a friend or disaster nudges us into baby steps of expansion. We’re all both irritating and a comfort, our insides both hard and gentle, our hearts both atrophied and pure.

How did we all get so screwed up? Putting aside our damaged parents, poverty, abuse, addiction, disease, and other unpleasantries, life just damages people. There is no way around this. Not all the glitter and concealer in the world can cover it up. We may have been raised in the illusion that if we played our cards right, life would work out. But it didn’t, it doesn’t.

[…]

Even with the Internet, deciphering the genetic code, and great advances in immunotherapy, life is frequently confusing at best, and guaranteed to be hard and weird and sad at times… We witness and try to alleviate others’ suffering, but sometimes it just outdoes itself and we are left gasping, groaning. And running through it all there is the jangle, both the machines outside and the chattering treeful of monkeys inside us.

Lamott reflects on the improbable relationship between brokenness and joy:

The lesson here is that there is no fix. There is, however, forgiveness. To forgive yourselves and others constantly is necessary. Not only is everyone screwed up, but everyone screws up.

How can we know all this, yet somehow experience joy? Because that’s how we’re designed — for awareness and curiosity. We are hardwired with curiosity inside us, because life knew that this would keep us going even in bad sailing… Life feeds anyone who is open to taste its food, wonder, and glee — its immediacy.

More than a century after Alice James — Henry and William James’s brilliant, underappreciated sister — observed from her deathbed that “[this] is the most supremely interesting moment in life, the only one in fact when living seems life,” Lamott adds:

We see this toward the end of many people’s lives, when everything in their wasted bodies fights to stay alive, for a few more kisses or bites of ice cream, one more hour with you. Life is still flowing through them: life is them.

[…]

That’s magic, or the human spirit, or hope — whatever you want to call it — to captivate, to share contented time.

Complement this particular portion of the wholly splendid Almost Everything: Notes on Hope with Joan Didion on learning not to mistake self-righteousness for morality and Ann Patchett on why self-forgiveness is the pillar of art, then revisit Lamott on friendship, finding meaning in a mad world, how perfectionism kills creativity, and her magnificent manifesto for handling haters.

Syndicated from Brain Pickings. Maria Popova is a cultural curator and curious mind at large, who also writes for Wired UK, The Atlantic and Design Observer, and is the founder and editor in chief of Brain Pickings (which offers a free weekly newsletter).

On Jan 8, 2019 Patrick Watters wrote:

Love this from “soul sisters” Maria Popova and Anne Lamott! }:- ❤️

Post Your Reply