Activism in a Pandemic: Progressive Examples from Australia's Past

Each month the Commons Library provides a small taste of actions and events which challenged the status quo and pointed to better ways forward via our ever growing From Little Things Big Things Grow: Events That Changed Australia list. These posts generally focus on events from a particular month, but in response to the Coronavirus pandemic we’re also sharing protests, campaigns and events from the past which highlight ways in which we can undertake action whilst maintaining safe health practices.

Please note: Levels of restriction and legal parameters vary across countries and even within countries. Many places are experiencing changing laws and different levels of policing related to the Covid-19 pandemic. What is an ‘arrestable action’ in one place may not be in another. Check the legal situation in your area prior to acting. Ensure public health and safety is a central consideration of any plans.

Car based actions

Car based actions have been tried in Australia and overseas as an alternative to rallies and marches during the pandemic. Cars provide a way to bring protesters together without risking infection. However, it should be noted that recent car cavalcades and convoys in Australia (April 2020) have resulted in fines for some participants and in one case a charge for an organiser. Victorian Police have emphasised the four acceptable reasons to be outside of homes and the fact that protest is not one of them.

Attaching banners to vehicles and creating floats has long been a part of May Day and other demonstrations and was used to great effect during the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, as seen in these black and white photos from the Search Foundation’s Tribune collection (more of which can be viewed via the State Library of NSW’s catalogue).

Slogans can also be written on vehicles as has been done in recent years in Australia by ambulance drivers and others in support of industrial action over wages and conditions.

Slogans can also be written on vehicles as has been done in recent years in Australia by ambulance drivers and others in support of industrial action over wages and conditions.

Boycotts

Boycotts are a long established tactic for pressuring and punishing companies for their social, industrial and environmental misdeeds as well as a way of bringing attention to them. They have generally been most successful when combined with other forms of action as part of a broader campaign and when they are highly targeted, connected to clear demands and placed on those most vulnerable to consumer pressure.

At times boycotts and have been used as a way of collectively responding to price hikes and gouging. For example in 1948 unions and community members in Werris Creek, NSW placed “black bans” on bakers and prevented them from forcing up prices. In Broken Hill union bans and a community boycott defeated attempts by retailers to ramp up prices after official price controls were lifted on fuel.

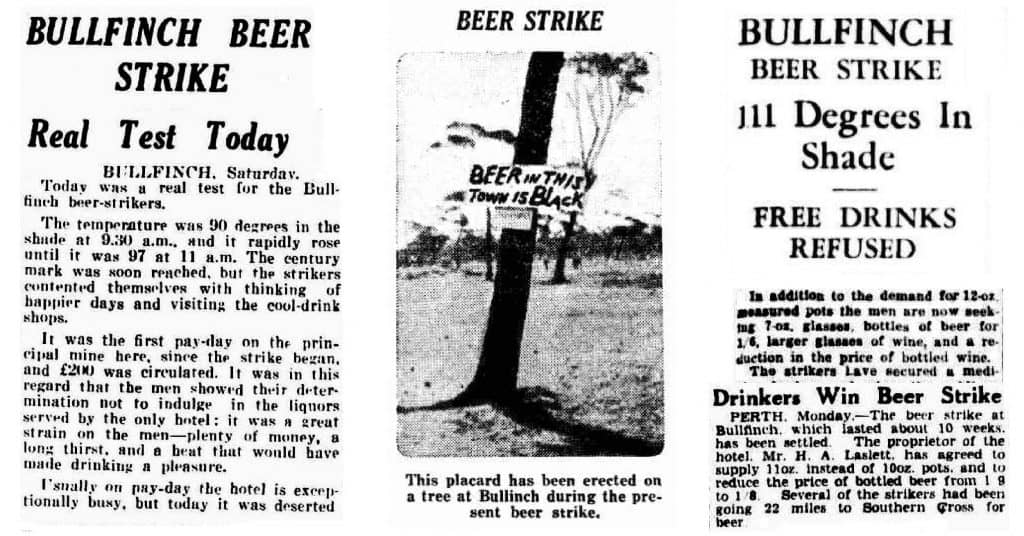

From the late nineteenth century until the 1940s “beer strikes”, boycotts of establishments that attempted to hike prices, were a common occurrence across Australia. These protests were generally informal affairs confined to remote towns, such as the one connected to the photo here, when a boycott was called in February 1932 in Western Australia’s Eastern Wheatbelt, in response to local hoteliers attempting to form cartels. Two years later a 10-week beer strike in the Flinders Ranges town of Quorn ended with publicans agreeing to lower their prices. In 1902 drinkers in the town of Mulline, WA who had been boycotting local pubs for a month over exorbitant prices, received a barrel of beer sent by supporters from nearby Menzies. At other times beer strikes were connected to broader issues such as supporting bar staff during strikes, resisting rationing and budget cuts during World War II and opposing autocratic rule in the Northern Territory.

Listen to the For the Win podcast about the AMWU’s 2017 boycott of Street’s Ice Cream in support of workers facing pay cuts.

Flags and banners

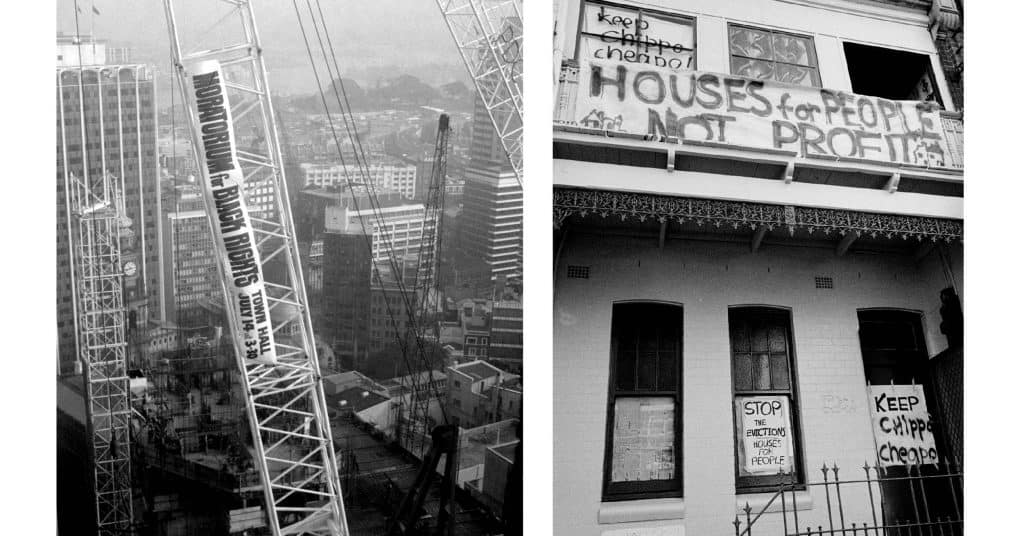

The use of flags and banners goes back to some of Australia’s earliest rebellions and they remain an important part of social and political movements today. Most often associated with street protests they can of course be hung anywhere. As with all forms of visual protest placement is key. In one example here we see a banner, backed up with placards, that was placed on a Chippendale home in 1980 as part of resistance to the eviction of low-income people from the area. The other image shows one of many banners hung from cranes by the NSW Builders Labourers Foundation in the early 1970s, this one in support of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander land rights. Both photos are from the Search Foundation’s collection of photos that originally appeared in the Tribune.

Creating banners and locating them on overpasses is a safe and effective way to get messages out to potentially thousands of drivers. These examples are drawn from a variety of Australian campaigns, organisations and collectives over the past ten years.

Posters and placards

Putting posters and placards in windows and outside homes is a tactic that has long been used to show the breadth of community support for a campaign or issue. With physically distant ‘bear hunts’ (inspired by the children’s book We’re Going On A Bear Hunt) going on around the world, in which people are placing teddy bears in windows so that kids can spot them on walks, such posters are more likely to be seen than ever.

In these examples we see the “Escaped Refugees Welcome Here” poster that was produced by Deborah Kelly to help people show solidarity with refugees who escaped from the Villawood Detention Centre in 2001. This was emailed out in an easy to reproduce format and soon seen across Australia.

Workplace organising and resistance

Since colonisation began the only rights Australians have gained in the workplace have come about through fighting for them. Australia currently has a number of repressive and restrictive laws and rules which, on paper, can make it difficult for workers to legally take industrial action outside of a bargaining period. However, as recent workplace action in warehouses and universities has shown it is still legal to walk off the job, refuse to do tasks and take other action over Occupational Health and Safety issues.

Beyond this there are actions which take things up to the edge of workplace restrictions and may exploit loopholes and grey areas. Some of the ways workers have pressured employers and demonstrated collective strength include taking coordinated breaks so that everyone is away from the job for a defined period, working to rule, working at a healthier/slower pace than normal, overwhelming managers with queries, taking sick leave en masse and informally agreeing amongst themselves to refuse to do overtime. At times industrial relations laws have been openly defied and broken as well.

Most of the following did not involve physical distancing, but are historical examples of alternatives to walk-off strikes that could be adapted to present day needs.

In 1798 Australia’s first “work to rule” action took place after convicts were reprimanded for not taking their hats off to officers whenever they passed by. Shortly after the order was given a work gang rolling a boulder uphill doffed their hats appropriately with the result that the rock rolls away, knocking an overseer down and breaking his leg. As part of what the Principal Superintendent of Convicts described as “continual warfare” between forced domestic labourers and masters, Tasmanian convict Eleanor Redding was charged in 1836 for turning her boss’s shirts into “pasteboard” after he complained of her using insufficient starch.

As indicated by this photo and caption from 1953 ‘Go Slow’ actions were once a regular and well known part of Australian workplace life. Following the failure of other action against being forced to work for the dole, a group of former Melbourne dock workers ordered to shovel sand in a relief scheme ran competitions in 1934 to see who could work the slowest. The construction of brushes and brooms at a Hobart based institution for the disabled dropped to negligible levels in 1945 when sight impaired workers slowed their rate of work in pursuit of improved sick pay. Demanding equal pay with male co-workers women factory workers in Newcastle, NSW stopped work for 15 minutes an hour during shifts in 1954 to ensure that their work rate reflected their pay rate. Two years earlier female office workers in the Victorian Railways Department had slowed the answering of phone calls to one every three minutes as part of pay negotiations. In 1967 postal workers in NSW, Queensland and WA followed each and every regulation and rule to the letter causing huge slow downs in the rate of work.

For more information about Occupational Health and Safety and other rights contact your union. Further information about workplace organising and tactics can also be found in Organising and Workers Rights in the Pandemic: A Beginner’s Guide by Jerome Small for Workers Organising Resistance in the Pandemic (WOR).

Objects to represent people

How can we show that many people care about an issue, without people being physically present like a traditional rally or march? One option is to have an object stand in for those people.

An example of this approach from Australian social movement history is ANTaR’s Sea of Hands. The Sea of Hands was made up of simple plastic cut outs of hands in different colours. When ‘planted’ they had a visual impact similar to mass plantings of flowers, but with political meaning related to the colours chosen (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander flag colours), the location of ‘plantings’, and the campaign context.

The first Sea of Hands was held on the 12 October 1997, in front of Parliament House, Canberra. Each hand carried the signature of someone who had signed the Citizen’s Statement on Native Title, a petition circulated by ANTaR to mobilise non-Indigenous support for native title and reconciliation. The Sea of Hands was then used for ongoing reconciliation campaigning, with installations in every major city and many regional centres, continuing to gather signatures. 120,000 hands carried over 300,000 signatures.

This approach is ripe for adaptation! The ‘planting’ can be carried out by a small number of people observing physical distancing and safe practices. Materials that are more environmentally friendly than plastic can be used. In other actions shoes have been used to represent the people who would be there if they could.

Photo: ANTaR, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Boat banners and protests

Restrictions on recreational and other boating are soon to be lifted in Queensland and Western Australia. Continuing our theme of forms of protest that can be used in a time of physical distancing we now turn to displaying banners, slogans and flags on water.

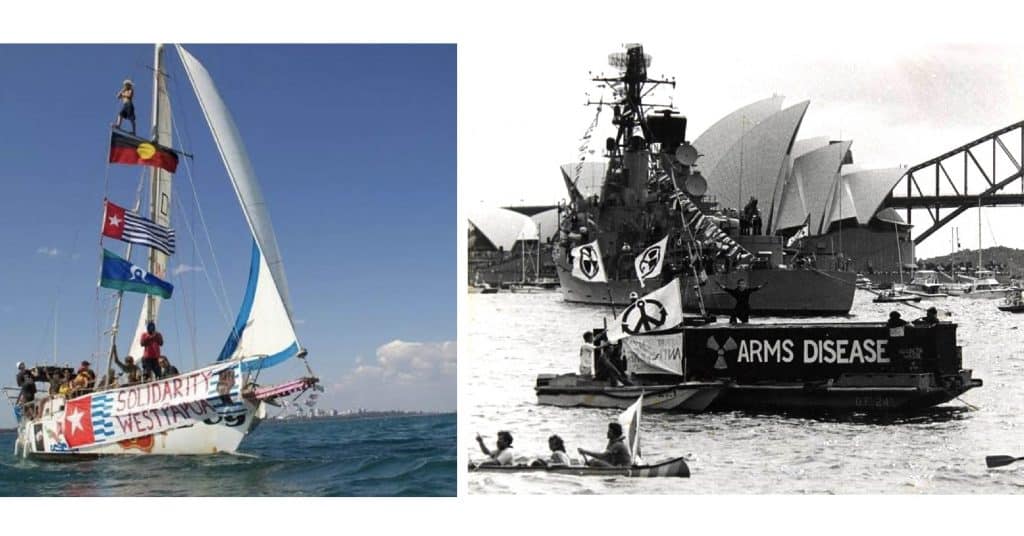

Boat based actions were a regular feature of environmental, peace and anti-nuclear protest during the 1980s and 1990s. Canoes and other vessels were used as part of the Franklin Dam blockade and numerous actions were held which aimed to blockade visits by US and other warships as well as the prevent the loading of uranium exports from Australia and the delivery of timber looted from overseas rainforests. More recently water based actions have focused on coal exports, refugee rights and West Papuan freedom struggles. Banners, flags and other means of messaging have often been a key feature of such actions, whether they involved physical obstruction or not.

The first photo is from the Freedom Flotilla protest. An initiative of Australian and West Papuan Indigenous elders, it traveled around both countries in 2013 to highlight and show solidarity with community struggles against colonialism. The photo comes courtesy of alliancesail.org. The second photo, taken from the National Museum of Australia’s Benny Zable collection, shows a barge set up to resemble a coffin taking part in a 1986 protest against the 75th Anniversary of the Royal Australian Navy, which included nuclear capable ships from other countries.

Brand correction

During physical distancing those seeking to ensure truth in advertising and brand correction can still do so through the addition, deletion and alteration of text and images via stickers, posters and other means. Back in the 1980s and 1990s Billboard Utilising Graffitists Against Unhealthy Promotions (BUGA-UP) revised hundreds of misleading advertisements around Australia. Their work played a major role in forcing health issues related to tobacco and alcohol onto the public agenda, changing the narrative around sports sponsorship and the image of drug dealing companies in the process. This image originally appeared in BUGA-Up’s catalogues during the 1980s. For more see this interview with a member of BUGA-UP.

In more recent times activists seeking to highlight the role of major banks in accelerating climate change have used similar tactics. In mid-2019 the Commonwealth Bank became the first major Australian bank to signal it would pull out of thermal coal production, although not fully until 2030 and until Australia has a “secure energy platform.” Coal Bank images appeared on various Facebook pages during 2017 and 2018.

High elevation

Even as Covid-19 restrictions begin to ease in parts of Australia it still appears that it may be some time before we can safely get back to holding mass actions such as rallies and blockades, at least in the ways that we’ve usually carried them out. One form of action with a long history of practicing physically distancing has been high elevation occupations. Recently a local resident in the Warburton Ranges occupied a tree for 3 days to prevent the woodchipping of forests and associated threats to water supplies.

Often associated with the defense of the environment, the use of platforms and other devices have been used in Australia for decades as means of maximizing disruption to destructive practices whilst minimizing costs in terms of arrests and fines. Occupiers are difficult to safely remove and, as they are, others can be brought in to replace them. Tripods were first invented and used 20 years ago in Australia to protect old growth forest in NSW and variations such as bipods, monopods and cantilevers later added to the toolkit.

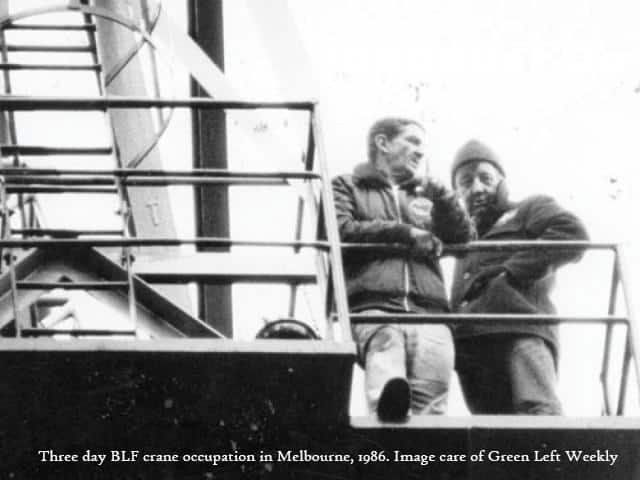

The use of high elevation occupations has gone way beyond defense of nature in Australia. Before environmentalists took to the skies builders labourers in NSW and Victoria were occupying cranes in the 1970s and 1980s to bring workplaces to a halt as part of industrial action aimed at maintaining union recognition and improving safety, wages and conditions. Climbing gear, tripods and other means have also been employed in banner hanging and direct action regarding refugee rights, anti-militarism and other issues.

This kind of action should obviously be only undertaken with great care and training, particularly as authorities and others cannot be guaranteed to act safely. The Earth First! Direct Action Manual is one of various guides to the use of high elevation and other useful tactics.

Craftivism

With people staying at home so much domestic hobbies have boomed, creating an opportunity for craftivism. Tal Fitzpatrick defines craftivism as “both a strategy for non-violent activism and a mode of DIY citizenship… Craftivism can take the form of acts of donation, beautification, notification or be deployed for its individual capacity building and therapeutic benefits, or for its ability to strengthen social connections and enhance community resilience.”

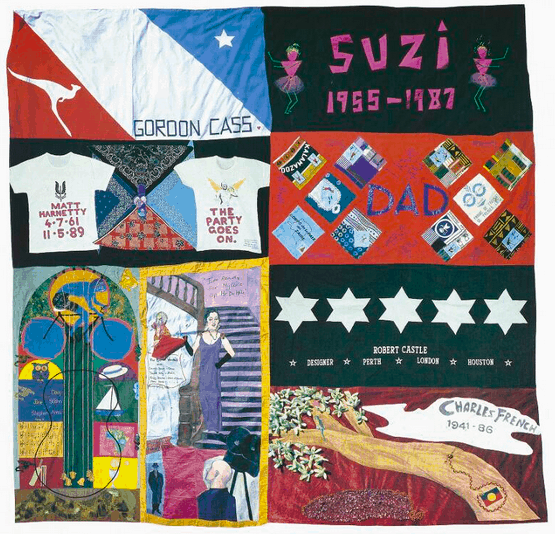

Although craftivism involves individual creative expression it can be powerful as part of a collective project. An example is the AIDS Memorial Quilt. The Quilt Project started in the USA in 1985 and spread around the world, with the aims of providing creative expression for those whose lives have been touched by the AIDS epidemic; illustrating the impact of the AIDS epidemic by showing the humanity behind the statistics; and reducing HIV/AIDS related discrimination and to provide support for preventative education. The Australian AIDS Memorial Quilt was launched in 1988 with 35 panels, growing to 122 quilt blocks, each with around 8 panels, commemorating approximately 2,700 Australians who have died of AIDS-related illnesses. Each quilt square is made by friends or relatives of someone who has died from AIDS related illness.

This example can be adapted for memorials related to the current pandemic, memorials to people or places lost by other means (for example a quilt square for each logged forest or extinct animal), or taken out of the memorial context to include protest messages and other focuses.

During Covid-19 precautions would need to be taken around handling fabric. Quilt squares could be fabric panels made separately then stitched together, or individually made squares photographed and stitched together electronically, or made entirely electronically for example via a template provided to supporters of a campaign to customise, before being edited together.

For history and images of the AIDS Memorial Quilt in Australia see the Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences. For more on craftivism see Craftivism: A Manifesto/Methodology and the Arts & Creativity topic on the Commons.

Clothing

T-shirts, vests and other forms of clothing and adornments have long been a big part of Australians expressing views and showing solidarity. With lock down restrictions being eased there are now plenty of options for flaunting fabulous phrases, scintillating slogans and ingenious images beyond the supermarket and the park.

For more on the history of Australian social movement events see From Little Things Big Things Grow: Events That Changed Australia.

See also Tactics that work during physical distancing: examples from around the world.

For more ideas on developing campaign actions see:

Gene Sharp’s 198 Methods of Nonviolent Action and the translation of those tactics into digital forms in Civil Resistance 2.0: 198 Methods Upgraded

Beautiful Trouble’s Guide to Activism During the Coronavirus Pandemic

Syndicated from The Commons Social Change Library. This online library is a space for education and learning. Its collections include articles, manuals, training materials and practical guides to inform and equip you to influence public policy and engage in political structures. Attribution CC BY. More by Iain McIntyre here