My Mother Against Apartheid

The author's childhood home in Port Elizabeth in the Eastern Cape between South Africa's Garden Route and the Wild Coast. Courtesy of Susan Collin Marks.

The author's childhood home in Port Elizabeth in the Eastern Cape between South Africa's Garden Route and the Wild Coast. Courtesy of Susan Collin Marks.

In 1948, the year before I was born, South Africa’s apartheid government was voted into power. Soon new, repressive laws were passed and discrimination against Black South Africans fast became the institutionalized norm, crushing lives into even smaller boxes through harsh legislation, forced removals from urban areas, and relentless persecution in the name of state security. My school friends thought this was natural because it was all they knew. Yet my mother had taken me into Black townships so that I could see for myself what cruel hardships apartheid imposed.

In 1955, six White women in Johannesburg said enough is enough when the government enacted a law to disenfranchise “Coloured” (mixed-race) South Africans, rescinding their right to vote. Along with a wave of other women, my mother, Peggy Levey, joined this group. Their formal name was the Women’s Defense of the Constitution League, but everyone called them the Black Sash. She was soon elected regional chair.

We lived in Port Elizabeth in the Eastern Cape Province, a world away from Johannesburg. My mother was regional chair of the National Council of Women and would later be mentioned as a potential candidate for Parliament. Now she stood in the town square carrying a placard and actually wearing a black sash to mourn the death of the constitution, as the government set about eliminating the few remaining rights of non-White South Africans.

It is hard to convey the courage and conviction it took to join, let alone lead Black Sash in a police state. Members were spat on and sworn at as they held their placards, and some old friends avoided them, afraid of association with dissidents. Some of my classmates weren’t allowed to play with me after school. But for my mother, Black Sash was only the beginning.

Next, she became Vice-Chair of the Regional Council of the Institute of Race Relations, a member of the Defense and Aid Fund Committee that offered legal representation for political detainees, and a leading light at the School Feeding Fund providing food for Black children who otherwise went hungry.

She also arranged food, clothing, books, money, and exchanges of family letters for internal exiles sent into the wildness of the veldt as a punishment for protesting apartheid.

That’s not all. My mother organized support for people forcibly removed from towns where they had lived for generations. This was occurring regularly as White areas were “cleansed” of Blacks. And she offered daily, practical help to a constant stream of Black South Africans caught up in the bureaucratic nightmare of dispossession. She found allies in government agencies who could keep families together and get life-saving pension and disability payments through the almost impenetrable Catch 22 of South Africa’s many new laws and regulations. She marched into police stations demanding to see detainees wrongfully arrested, scandalously took tea with Black people in our living room, wrote endless letters to the newspaper, and spoke out publicly against the system.

Peggy and Sydney Levey on their wedding day in 1944. Peggy was a lieutenant in the South African Air Force.

Peggy and Sydney Levey on their wedding day in 1944. Peggy was a lieutenant in the South African Air Force.

It was only a matter of time before the authorities would go beyond their routine of raiding our house and tapping our telephone. In 1964, they threatened to ban my mother unless she stopped her subversive activities.

It was probably her work with the Christian Council for Social Action, providing food and clothing to families of political prisoners, that made her a target. The Council had been visited by the Special Branch three times in the previous two weeks.

She was charged under the Suppression of Communism Act, but of course that had nothing to do with it.

Banning was extra-judicial punishment. There could be no appeal. The sentence lasted five years, and was often renewed the day it ended. A ban consisted of a curfew that amounted to house arrest, reporting to the police every day, and severing contact with other banned or imprisoned people. And always being watched.

For my mother, these restrictions would be excruciating. Her mother was dying 700 miles up the coast in Natal. We children were at boarding school 80 miles away. And my father feared for the safety of his family. The conflict in my mother’s heart and in our home was unsustainable. If she didn’t stop her work voluntarily, she would be stopped by the terms of the ban. To give up the activism that gave her life meaning was unthinkable. And yet so much was at stake: her relationships with her mother, her husband, her children, even her own life. And so she stepped back, feeling profoundly divided. Eighteen months later, she found the first trace of a cancer that would eventually kill her.

From the Port Elizabeth Herald, 1964

From the Port Elizabeth Herald, 1964

This is how my mother joined the ranks of people who had fought apartheid, and, ostensibly lost. Of course they hadn’t. Every effort counts in the Book of Life. She refused to be bitter and afraid. Her steady dignity and courage were a triumph of the human spirit.

In the 1970s, she quietly resumed her work, supporting individuals and families who came to her door. Word spread like a bush-fire that Mrs. Levey was back, and lines of people waited patiently in the courtyard of our house, hidden from the road, nosy neighbors and the police, with plates of food on their laps.

They all were desperate. The bureaucracy, always a maze of impenetrable regulations, had tightened its grip. As the years went by, it devised more and more obstacles for non-whites. I found this entry in one of her notebooks: Disability and Old Age Grants can only be applied for at Africa House during the first three weeks of alternate months.

Ordinary citizens didn’t know this, and after traveling for hours, they stood helplessly in front of closed doors or were told to come back in a few months to bring papers they didn’t have. Meanwhile, life-giving pensions and work permits sat on desks of bureaucrats. They might as well have been on the moon.

Families were left destitute when their chief breadwinners were picked up by the police under the Suppression of Communism Act that allowed detention without trial. This happened routinely to those suspected of sympathizing with African National Congress.

In anguish, my mother told me about a woman with six children who had been thrown into the street, without money or food, after the police had taken her husband in the middle of the night. The landlord didn’t waste time evicting her, knowing she couldn’t pay the rent. It was a story repeated thousands of times.

My mother kept a series of notebooks, detailing the cases she handled on a daily basis. Most were about sheer survival. Families depended on disability grants, old age pensions, permits for the city and a place to live. They also needed “work seekers” – papers allowing them to look for a job. Food was scarce and so was medical care. Children had to be found and released from jail, missing people traced, exiles contacted, lost papers replaced. The best word in my mother’s notebook — “fixed.”

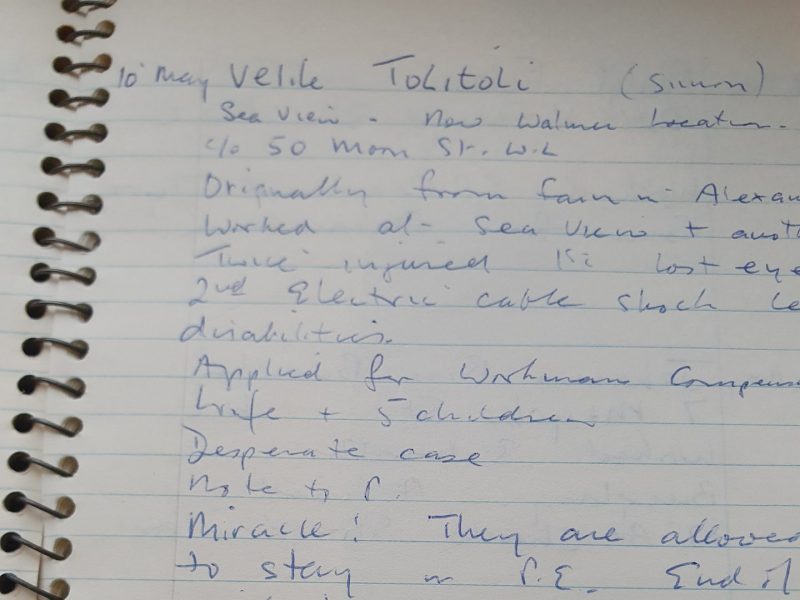

Peggy Levey's case notes

Peggy Levey's case notes

Of course the authorities knew. Later, the government would take away her passport, and only grudgingly return it when she sought treatment for her cancer in the Unites States. Even then, they sent an agent to watch her every move. And of course, she resumed her work when she returned to Port Elizabeth.

From her desk, at home, she wrote letters to the authorities, hospitals, charities, and newspapers. And she plotted her next steps before picking up the black rotary phone in the front hall and calling the Department of Labor, the police, the municipality, the African Affairs Department, a social worker. She found brave and good-hearted bureaucrats who would help, and on occasion stick their necks out, like Paddy McNamee at Africa House. On September 20, 1976, she wrote, “he has worked a miracle in the case of Felix Kwenzekile.”

Felix had lived in Port Elizabeth for 14 years, and left to look after his brother who died ten months later. When he tried to return, he was refused the necessary papers. Thanks to Paddy’s intervention, he could stay, yet there were other complications. On October 7, my mother wrote: “Felix is taken on by Port Elizabeth Municipality but will only receive his first pay October 14. So they (his family) are starving. How many others suffer like this?” Or course, she gave him money and a food parcel to tide him over.

These are some of the other entries in my mother’s casebook:

10 May, 1976. Velile Tolitoli. Originally from farm. Twice injured, 1st lost eye, 2nd electric cable shock, leg disabilities. Applied for Workman’s Compensation. Wife and 5 children. Desperate case. Note to Paddy McNamee.

The notebook lists other new cases – John Makeleni who has lost his papers, gets his old age pension when Mr. Killian, intervenes. Lawrence Lingela, an epileptic who thank God has his medical report, gets his disability grant.

Johnson Qakwebe, originally from a rural area, must suddenly prove he has been in Port Elizabeth for 15 years or be sent back to a jobless place in the middle of nowhere. My mother visits a family that has known him since he first arrived in Port Elizabeth and they write letters of recommendation.

Oerson Willy, an ex-convict, finds a job.

Madelene Mpongoshe’s house burns down, and when she goes to the housing office, she is told she must produce her reference book, the precious document that allows her to live in the city. But it was lost in the fire. My mother phones an official, Mr. Vosloo, who can replace it.

Mildred Zatu, an old age pensioner confined to one room, is very unhappy – my mother invites her to lunch at our house each Monday and finds a better place for her to live.

Grace Mqali is trying for a disability grant. The forms are completed and handed in—and seven months later, they are approved.

William Mvakela has tax problems with his old age pension, fixed.

But then there are a few that slip through the cracks. Philip Fulani comes once and then disappears, perhaps to prison, perhaps giving up and going back to Grahamstown which he left because there was no work.

Years later, when I am working in the peace process at the heart of South Africa’s transition from apartheid to democracy, I attend a political funeral in Langa, a Black township on the edge of White Cape Town. Arriving late, I cram into one of the last remaining seats, jammed up against a pillar. A poster stares down at me for the next three hours.

If you have come to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.

I know I am not here, in this seat, by chance. The words on the poster link me directly to my mother.

On her death bed, she had dictated three pages of instructions to my brother about her active cases, including what to do about a resettlement camp at Ilinge, in the middle of nowhere. Years before, hundreds of Black people had been dumped there, wrenched from their homes because the boundary between Black areas and White needed to appear on a map as “a straight stripe.” These families had a tent and little else, and found themselves far from work or services. For years, my mother had provided the women with sewing machines and material so that they could make a living. Their situation was on her mind to the last. She died two hours later. She was 67.

A few days later, the phone rang. Busloads of Black township men and women wanted to come to the ceremony, which would be held in a White church in a White area. I said yes, on one condition—that they not sit at the back of the church.

After the packed congregation had sung a sang subdued All Things Bright and Beautiful, the cadence and harmony of an African hymn filled the church. Then I sat on the lawn as the crowd drank tea and orangeade and sang Nkosi Sikelel’i Afrika (in Xhosa, Lord bless Africa), a pan-African liberation song that was banned under apartheid. I smiled and knew that my mother would be smiling, too.

My mother was celebrated in the Black townships as amakhaya, meaning “of our home” in Xhosa, signifying that she was “one of us.”

At the beginning, she didn’t know she could change anything. But in the darkest days of apartheid, she learned to jump at the sun.

This brutal system ended with the election in April 1994 of Nelson Mandela as the first president of a democratic South Africa. Tears were streaming down my face as I marked my X next to Mandela’s name. I knew that my mother and I both held that pen.

The author serving as a peace maker in Angola in 1996

The author serving as a peace maker in Angola in 1996

***

Join this Saturday's Awakin Call with Susan Collin Marks, "Wisdom and Waging Peace in a Time of Conflict." RSVP and more details here.

This article appears in the Spring 2021 Edition of Reinventing Home at www.reinventinghome.org. Susan Collin Marks was at the heart of her native South Africa’s transition from apartheid to democracy, as described in her book, Watching the Wind. With Search for Common Ground, founded by her husband John Marks, she has worked in over 50 countries, helping to build peace in the world. This article was adapted from her forthcoming memoir, Singing Peace: Wisdom in a Time of Conflict.

SHARE YOUR REFLECTION

3 Past Reflections

On Mar 24, 2021 Kristin Pedemonti wrote:

Thank you for sharing your mother's powerful story of resistance, impact and service. My heart and soul are deeply inspired and touched to continue standing up for those who are so unjustly treated and pushed to the fringes.

On Mar 24, 2021 Patrick Watters wrote:

Simply powerful, endearing, and yes, motivating to carry on . . .

On Mar 24, 2021 Valerie Andrews wrote:

It was a privilege for us at Reinventing Home to publish Susan Marks's heartfelt story. And it's wonderful to see it here. This marvelous woman learned how to bring wisdom out of conflict, and build a strong sense of community, at her mother's knee. We all have an unsung hero, or heroine, who has quietly committed to the work of freeing others. Susan has been an inspiration to many world leaders working for peace. It's people like Susan, and her unsung mother, who make us all feel more loved, and more at home within the body of the world.

Post Your Reply