Leaf Seligman: On Redemption and Beautiful Scars

As humans, we inevitably experience harm: we feel hurt, we get hurt, and we hurt others. We free ourselves from this experience not by imagining we can escape harm but knowing we can heal it— moving from wound to scar—and then learning to love the scars. This can, of course, be the work of a lifetime.

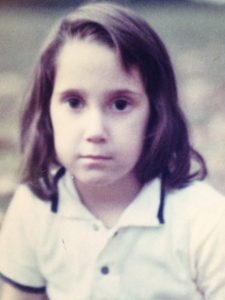

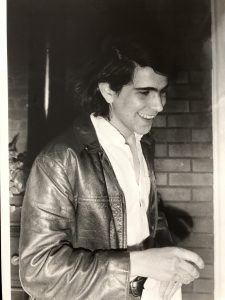

Luckily, I have long loved scars. When I was four, I accidentally cut my left eye. As a result, a small scar formed directly under my eye and inside the eye, where the pupil stayed dilated with a keyhole in it. After I had the eye removed at twenty-one, a photographer I knew told me she wanted to record people’s scars, so I asked her to photograph me with my empty socket. It may be that at twenty-one I looked youthful, even radiant, but that one-eyed image of myself is my favorite photo; in fact it’s the only picture of myself where the subject feels beautiful.

From childhood, I loved my left eye even though I lost sight in it early on, because it embodied strength. That scarred part of me told a story of a brave four-year-old, and the mother who never left my side, except for the long gurney ride to the operating room when I wailed for her and experienced a feeling of abandonment for the first time, full of utter terror and bewilderment that my cries did not bring her to my side.

From childhood, I loved my left eye even though I lost sight in it early on, because it embodied strength. That scarred part of me told a story of a brave four-year-old, and the mother who never left my side, except for the long gurney ride to the operating room when I wailed for her and experienced a feeling of abandonment for the first time, full of utter terror and bewilderment that my cries did not bring her to my side.

My mother slept next to me for a week in the hospital and then drove me every morning for the next twenty-one days to the ophthalmologist who changed my dressing and checked the wound. Despite the metal patch over my eye, the early morning car ride heading east proved brutal. My mother tried to soothe me, my head tucked in her lap as I lay across the front seat.

Later that same year, I asked her to call me “son,” because I knew in my small body a terrible mistake had occurred in utero. I was supposed to be born a boy like my older brother. I remember my deflation hearing her say she would not call me son because I was the little girl she had longed for.

One wound she knew how to tend, the other, she did not.

We all have our wounds. Unattended or ignored, they fester. When we acknowledge them, examining them as thoroughly and gently as the doctor checking my injured eye, we seed redemption. How we tell the story of an injury can transform it. When we give voice to trauma as neither victim nor villain, choosing to write ourselves as lovable, worthy, and accountable, healing begins.

We all have our wounds. Unattended or ignored, they fester. When we acknowledge them, examining them as thoroughly and gently as the doctor checking my injured eye, we seed redemption. How we tell the story of an injury can transform it. When we give voice to trauma as neither victim nor villain, choosing to write ourselves as lovable, worthy, and accountable, healing begins.

It is, however, an enduring process.

I adjusted to the scorch of sunlight when it hit my permanently dilated left eye by squeezing my eyelid shut and letting a hank of my hair cover the that side of my face. A carapace of sorts, protecting my eye, perhaps shielding me from the invisibility of my boyness, so evident inside me.

Much as I wanted to emerge from that shell, my body knew the blinding pain of exposure. At age six, I referred to my nondominant right hand as “my girl hand” because it was clumsy; when a tiny wart appeared near a knuckle, I slapped it with my left hand, punishing it for the additional ignominy of ugliness.

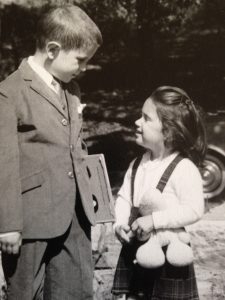

I kept emulating my brother, hoping the errancy of my femaleness would be redeemed.

At three, before I gave up dresses, I already longed to wear his suits.

At three, before I gave up dresses, I already longed to wear his suits.

And when he—the only boy I could imagine loving—disappeared at age fourteen to attend prep school, the year I was nine, a chasm opened. He left me alone with our mother and a mysterious younger sister who screamed daily for hours though she did not speak or walk until age two. Our father came home later and less often as my brother, the bulwark against my loneliness, traveled out of sight, touching back down in four years when he graduated, after our parents divorced. Like a blinded sibling reaching for the comforting braille of his body, I sought his company throughout the summer of his return. August 20th he died in a fiery wreck at four a.m., his sports car colliding with a tree. I learned later, the woman inside the house where he crashed was awake at the window nursing her newborn. So often I have thought of her witnessing that, wondering what story might she have told.

August 1972.

After my brother’s death, I entered a state of suspended animation, unable to find a place to hunker down in my grief. I watched and waited for my maleness to visibly emerge, certain it would descend like recalcitrant testicles but at thirteen as my relatively androgynous child body inched toward femaleness, the only thing I knew about being female was that meant being sexual with boys. Those were the only stories I knew so the wound widened around the lack of better ones and abscessed over unexpressed grief.

I betrayed myself with boys nothing like my inner one. No tenderness in them as they pressed themselves into places so tender in me.

Redemption happens when we acknowledge the true nature of the hurt we experience. When we name the harm, tell the story, notice the nuances, lean deep into the interstitial silence, listening for what gets revealed in what remains unsaid. Healing blooms in the respite of deep breaths giving space to exhale grief, anger, emptiness, bewilderment, and pain. The disappointment of disappearance and departure.

When we relinquish blame, shame, and the lingering patter of the inner-critic quick to pronounce fault —choosing instead to hold ourselves in compassionate embrace with tenderness, we can step back enough to see the fullness of each unfolding story.

The recognition that my brother’s leave-taking, and my father’s, and decades later, someone else I fiercely loved, reflected their journey not my desirability or worth— freed me from a lifelong narrative of abandonment, shaping a new story of redemption.

Recently my ninety-one year old mother shared a library book her librarian friend had chosen for her, Love Lives Here: A Story of Thriving in a Transgender Family. At lunch, she apologized for not recognizing the wound and for the harm she caused denying my request at age four. Her voice cracked. Her eyes welled.

“The other day, I heard you describe yourself as a sixty-one year old woman dressed like a ten-year old boy.”

It’s an accurate descriptor. I identity as female. I am finally at home in my body and most of the time that’s how I dress. I still carry the carefreeness of the boyhood I imagined for myself.

“I wonder if what you really want is just to be able to be Leaf.”

Yes.

The wounds turn to scars as the story changes.

I redeem myself from the hurt I’ve experienced by freeing myself from feeling victimized, somehow deserving of the harm or deliberately targeted for it.

Revising the story doesn’t deny grief. It honors the depth of it.

The leave-taking that occasioned my loss wasn’t about me any more than a tornado blowing through. Life happens. We form emotional attachments and desire proximity. When someone needs to leave or is forced to, it disrupts the proximal connection and that often hurts. It might end physical intimacy and that loss is real. What disappears does not erase what existed.

I free myself from harm when I realize the energy of the connection remains in the cosmos, just as the essence of who we and the energy of our bodies releases into the atmosphere upon death.

Redemption happens when I remember that.

Last year during a conversation about the three decades I attended twelve-step meetings, the person asked what I am recovering from. I responded, “the human condition.” Being human was the cause of the half-dozen drinks and relationships I picked up to quell feelings of insecurity and unworthiness. I redeem myself from the harm I caused or occasioned by being responsible: traveling the distance from intention to impact.

Redemption happens through a process of accountability: acknowledging the effects of our behavior and asking what needs arise as a result. We must address those needs to repair the harm we caused— and insure we won’t repeat it by healing the harm we carry within.

Redemption happens when we free ourselves and others from the static roles of victim and victimizer. It is only in an uncondemned state that any of us can change.

When we recognize the complexity of each person who appears in our story, acknowledging that their story is bigger than the role they play in ours, then all our stories can continue to unfold.

Redemption happens when no one is condemned to stasis—the impossibility of revision.

Redemption happens when we craft the story we need to re/claim ourselves.

For much of my life, I turned away from myself and from a sense of belonging. Like Cain, I set off to wander in the wilderness, full of remorse, laden with shame. A childhood that felt like my body betrayed me had more to do with the collective stories that betray so many of our truths. Toni Morrison wrote her first novel The Bluest Eye because she said it was the book she needed to read and no one else had written it.

I imagine vocation arises that way for many of us—meeting a need so essential within ourselves that serves the world as well. For me it’s redemption. Whether it’s writing, teaching, preaching, circle-keeping, or just providing warm accompaniment, it’s all an invitation to move from wound to scar, from constraint to release, from leave-taking to letting go, from exile to belonging.

Redemption happens when the unfolding of our stories lets every part of us breathe, exposing our fullness, leaving no corners for shame to gather or harm to accrue. Wholeness is where healing happens, creativity flows, and the spirit enlivens.

Redemption invites us to inhabit the human condition in lieu of having to perpetually recover from it.

photo by Kim Cunningham

***

Join a special circle with Leaf Seligman this upcoming Wednesday, July 7th: The Magnificent Broken- Redemptive Healing Through Words. More details and RSVP info here.

Syndicated from Leaf Seligman's website. Leaf Seligman began writing during her Tennessee childhood where she encountered the midway, tent revivals, and the Civil Rights movement. She has taught writing in colleges, jails, prisons, and community settings since 1985 and worked as a minister, a jail chaplain, a youth services caseworker, and a restorative justice practitioner. She is the author of Opening the Window: Sabbath Meditations, From the Midway: Unfolding Stories of Redemption and Belonging, and A Pocket Book of Prompts.

SHARE YOUR REFLECTION

3 Past Reflections

On Jul 4, 2021 Kristin Pedemonti wrote:

Thank you Leaf for reminding us of our multitude of stories and our choice in the telling. Ah, sweet redemption, so exquisitely expressed.

I'm grateful to now be studying Narrative Therapy practices which honor and acknowledge the many layers and influences on each of our stories. It's like finally having words to fully understand ♡

I'm melding Narrative Practices with the art of Kintsugi, mending the broken with lacquer and gold, it's been profoundly healing. Grateful.

Reading your words adds another beautiful layer of gold.

Love from my Kintsugi Life, celebrating my scars to your Kintsugi Life

Kristin

On Jul 4, 2021 Sidonie Foadey wrote:

Thank you, Leaf! Your words felt profound and soul soothing... Yes, I have eventually come to terms with the necessity of befriending my scars, a lifetime commitment. I am grateful for what this taught me and continues to do so. "Life happens, redemption happens". Worth being reminded, oftentimes. Namaste!

On Jul 4, 2021 Patrick Watters wrote:

Ah so beautiful indeed. Our wounds, our scars are sources of deep blessing and healing if we allow them to be. Leaf your story is very similar in many ways to my wife Patti Padia. She has her scare through one eyebrow, narrowly escaping with eye intact. She is at her lovable best in boyish dress and behavior, but oh so delightfully feminine too in her own way. I too have a similar story with a 124 stitch scar from childhood brain surgery. Whether our wounds are physical or emotional (I have much of both), they can indeed be sources of deep healing for ourselves and others too, if we can just get ourselves to surrender to love. }:- a.m.

Post Your Reply