James Doty's Helper's High

James Doty is not a subject under study at the altruism research center that he founded at Stanford in 2008, but he could be. In 2000, after building a fortune as a neurosurgeon and biotech entrepreneur in Silicon Valley, he lost it all in the dotcom crash: $75 million gone in six weeks. Goodbye villa in Tuscany, private island in New Zealand, penthouse in San Francisco. His final asset was stock in a medical-device company he’d once run called Accuray. But it was stock he’d committed to a trust that would benefit the universities he’d attended and programs for AIDS, family, and global health. Doty was $3 million in the hole. Everyone told him to keep the stock for himself. He gave it away—all $30 million of it. “Giving it away has had to be the most personally fulfilling experience I’ve had in my life,” Doty, 58, said on a recent sunny afternoon at Stanford. In 2007, Accuray went public at a valuation of $1.3 billion. That generated hundreds of millions for Doty’s donees and zero for him. “I have no regrets,” he said.

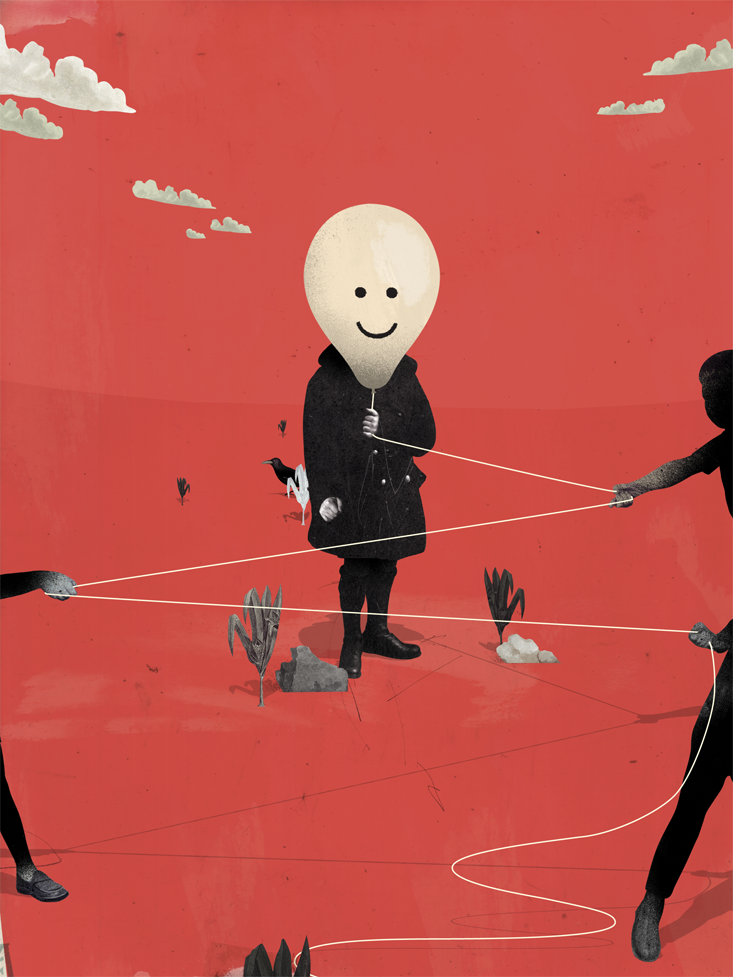

So what exactly is wrong with Doty? Is it normal for a human being to commit a generous act that helps others and not himself? Or is his selfless act merely an act of veiled self-interest? Anthropologists and evolutionary biologists have been wrestling with these questions for decades. Recent research suggests it’s more complicated than that—that evolution has pushed us toward a trait that binds communities and helps them prosper, and that altruistic acts promote individual well-being in biologically measurable ways. These are precisely the kinds of issues and questions that motivated Doty to form—with a seed donation of $150,000 from the Dalai Lama, whom Doty had met in a chance encounter—the Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education, or CCARE, part of Stanford’s School of Medicine.

In the past six years, CCARE has distinguished itself from other research centers because it’s determinedly multidisciplinary. Its affiliated scientists have conducted studies in areas from neuroscience and psychology to economics and “contemplative traditions” like Buddhism. But CCARE is distinguished in another way: Many of its core findings mirror Doty’s own life. Emiliana Simon-Thomas, a neuroscientist, the science director of the Greater Good Science Center at the University of California, Berkeley, and former associate director of CCARE, sees Doty as a remarkable embodiment of what researchers are learning about altruism. “He rose to absurd riches and found that having every possible need met isn’t better,” she said. “That kind of question motivates him. He’s gone to the extremes of the pendulum, and he’s trying to find the place in between that will bring him the most rich and authentic sense of purpose.”

Doty, an atheist, believes life, especially his own, revolves around the kindness of others. A tall, bearish man with a head of full gray hair, who is by turns pensive and cheerful, Doty acknowledged that he founded the center out of his own self-interest. “Every scientist is inherently biased, but the data is the data,” he said. “I am just as interested in the question of what blocks or prevents compassionate behavior, and what are the documented physiologic benefits, or not.” He added, “All of us have a back story, and how we function or behave today is a manifestation of what has happened to us in the past.”

From welfare to the penthouse: “You have to show everyone that you’re not inferior, that you’re as good as they are,” James Doty said of his drive to the high life.

From welfare to the penthouse: “You have to show everyone that you’re not inferior, that you’re as good as they are,” James Doty said of his drive to the high life.

Doty grew up in southern California, where his childhood was torn by poverty. His father was an alcoholic and often in jail, and his mother was ill. They lived on public assistance and bounced around from Torrance to Palmdale, fearing eviction at every turn. By age 13 he was doing drugs. “I wasn’t physically abused,” he said of his childhood. “But it just sort of sucked—you wouldn’t sign up for it.” One day Doty wandered into a local magic shop in a strip mall and met the owner’s mother. Though Doty didn’t think of himself as sullen or angry, he was at a critical juncture, and the woman in the shop saw that. She invited him to come back every day after school for six weeks, and taught him how to meditate. He practiced picturing things that he wanted to happen; it allowed him to see his way out of hopelessness.

“Take two people—both of them walk outside into the rain,” Doty explained. “One person says, ‘It’s been so hot lately, there’s been a drought, this rain is wonderful, all this growth is happening.’ Another person walks out, says, ‘My whole day has been bad, this is just another crappy part of it, traffic will be horrible.’ And yet they’re both swimming in the same pond.” What he learned from the woman in the magic shop changed not the reality of his external circumstance—he was still poor, and he was still the one who had to take care of his parents—but his internal perception of it. “We are the ones who create our world view—not some outside event or environment.”

The generosity of the woman in the magic shop unleashed a boldness in Doty. A high school friend was applying to the University of California, Irvine, and Doty decided on the spot that he would, too. She showed him how to fill out the form. He studied biological sciences at Irvine and decided to apply to medical school at Tulane. When the scheduler for the college pre-med committee told him he was wasting his time because of his dismal 2.5 GPA, he demanded a hearing so he could argue his worthiness; at the end, he had the committee in tears, and won the recommendation he needed for his application. At Tulane, despite a passed deadline, a woman in the program office showed him a small kindness by allowing him entry into a med-school program for disadvantaged and minority youth.

Goodbye villa in Tuscany, private island in New Zealand, penthouse in San Francisco.

In medical school, Doty’s ambition exploded. He aimed for the top of the physician totem pole and became a neurosurgeon. After earning his medical license he established a lucrative neurosurgery practice in upscale Newport Beach, California, and later at Stanford. But he didn’t stop there. Along with practicing medicine in the 1990s, he cast an envious eye on entrepreneurs riding a wave of venture capital investments in the biotech industry. Doty focused on Accuray—makers of a medical device called the CyberKnife, a device that could deliver targeted radiation therapy—which was going bankrupt. Like a skilled arbitrageur, he raised $18 million in investments, and personally guaranteed part of the credit lines himself. Doty became president and CEO of Accuray and sales of CyberKnife took off. He invested in other medical-device companies and his high life was in full swing. He drove a Ferrari and put a down payment on a 6,500-acre island in New Zealand.

Doty said his ambition was powered by the “monkey” on his back: the specter of his childhood poverty. “You have to show everyone that you’re not inferior, that you’re as good as they are,” he said. As someone who grew up in deprivation, he chased the money and the goods, hoping that it would translate into something. “Happiness, maybe,” he said. “Or control. You keep waiting for the magical event that will make you feel that you’re OK.” When he lost all his money, he said, “that released me from that monkey. I voluntarily gave away the thing that I wanted the most.” He paused, emotional in the recollection. “And then I didn’t have to worry about that anymore.”

Doty’s liberating act of philanthropy (although his not-yet wife Masha didn’t see it as liberating at the time) underscored his purpose as a physician. He took a leave of absence from Stanford and went to Gulfport, Mississippi, to start a regional neurosurgery and brain injury center, and was working there when Hurricane Katrina hit. He stayed two more years. When he returned to Stanford, it was with an idea to pay as much rigorous scientific attention to positive behaviors like compassion and altruism as he had to solving pathologies of the human mind. “I was struck by how sometimes it’s obvious that someone needs help, and one person gives it, but another won’t. But why wouldn’t you? That’s the burning question. I still don’t understand it,” he said with a rueful laugh. “People get so absorbed in how important their own thing is. But I assure you, if they were in the position of need, they sure wish someone would pay attention.”

Through CCARE, Doty is starting to get glimmers of understanding. Part of the center’s role has been to start a cultural conversation about why we treat others the way we do. Doty points to the work of Dacher Keltner, a professor of psychology at Berkeley, and Michael Kraus, a professor of psychology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; their studies have found that affluent people are worse at reading others’ emotions than people of limited means. Those who are rich also tend to be less compassionate and community-focused; the researchers suspect that the less we need to rely on others, the less we pay attention to them or care about their feelings. As global inequality rises, Doty said that the psychological understanding of how conditions of material wealth and social class may influence our behavior toward others will only grow in significance. “People who have been given certain privileges have the obligation to watch out for the weakest.”

Charles Darwin himself assumed that compassion was essential to the survival of our species; evolutionary theorists have speculated that the ability to recognize others in distress, and the desire to help, is critical to the care of vulnerable offspring, and to cooperation with non-kin. “We’ve kind of misread Darwin,” said Simon-Thomas, the Berkeley neuroscientist, who co-wrote the first evolutionary analysis and empirical review of compassion in 2010. “We’ve come up with the idea that ‘survival of the fittest’ means that the strongest man wins, when what actually wins is highly collective, communal behavior.”

What Doty may be proving with his own life is what the Dalai Lama has called “selfish altruism.”

When asked what researchers are discovering about the main scientific argument in altruism—are we selfish or selfless beings?—she laughed. “It’s definitely both,” she said. “We’re built to survive, and to be vigilant to threats to our individual integrity. But we’re also built to cooperate with others when we’re not under threat ourselves. You don’t try to comfort or hug someone who’s trying to attack you. But if you’re confronted with someone who is in deep, profound pain, it arouses in you a mirrored perception of pain itself, and it’s not always a service to yourself to run away from that.” The sensation of stress around both scenarios is similar, she said, but the way we relate and react to that feeling—fighting and escaping vs. approaching and helping—differs profoundly.

The two behaviors, Simon-Thomas explained, are reciprocal and dynamic. Despite the fact that up until now medical science has focused on sickness, pain, and disease, society has come to pay more attention to what comes after you’ve achieved physical health. “More and more of the science of well-being and happiness,” she said, “has to do with uncovering this second story about connecting, being kind, serving others, and functioning in a sustainable community.” Doty’s own life embodies her findings. “His personal history of struggle as a young person is instrumental to his sensitivity to suffering of others,” Simon-Thomas said. “He’s willing to talk to anyone. And willing to help in almost every case.”

What Doty may be proving with his own life is what the Dalai Lama has called “selfish altruism”—we benefit from pleasing others. When we help someone else or give something valuable away, the pleasure centers of the brain, or mesolimbic reward system, activated by stimuli such as sex, food, or money, provides emotional reinforcement. Functional magnetic resonance imaging studies by the National Institutes of Health have shown that the reward centers are equally active when we watch someone give money to charity and when we receive it ourselves; in addition, giving something valuable away activates the subgenual area, a part of the brain that is key in establishing trust and social attachment in humans and other animals, as well as the anterior prefrontal cortex, which is thought to be highly involved in the complexities of altruistic decision-making. What researchers call the “helper’s high” may be aided by the release of endorphins. By virtually every measure of health we know—reducing blood pressure, anxiety, stress, inflammation, and boosting mood—compassion has been shown to help us. These are some of the ways we are encouraged to establish trust and community, which have long been necessary to human survival.

The language of giving often gestures to reciprocity and symmetry. Humans are known to mimic each other, even at a subconscious level. One study of interpersonal synchrony used a metronome and showed that people who tapped a beat together would align themselves and support each other. “It’s finding similarities that make you identify with somebody else, or feel part of something, and this gets back to community, to being a part of something that’s greater than yourself,” Doty said.

The predisposition to feel compassion toward people in our in-group, but not our out-group, may be less useful in our modern society. We no longer live in small communities near people we have known and trusted all our lives; the world is wider and more accessible, and perhaps more threatening. But scientists are finding that even what is traditionally perceived as “bad” behavior can lead to greater good: A recent CCARE-funded study shows how gossip and ostracism encourage cooperation in groups. A seemingly anti-social behavior has, in the long run, positive results on community relations, by protecting cooperators from being exploited. The existence of selfish individuals and behaviors, then, may also play a role in encouraging the rest of us to be better.

Sitting in his office, Doty said the goal for his center is to translate what has evolutionarily occurred—our tendency to feel connection to family, to tribe, to nation—to extend to a common idea of the world being our collective home. “We have to go from this viewpoint that our family is defined by our mother, father, sister, brother, aunt, uncle”—he thumped his desk—“to saying the world is my home. And not be overwhelmed by that, to have a sense of open-heartedness about that. That’s what’s going to save our humanity.”

Not long ago, Doty struck up a casual friendship with a clerk at a San Francisco coffee shop he frequented. He learned she was a single mother with a 9-year-old child and that her dream was to be a doctor. She had dropped out of college but was working to get back. Every once in a while Doty asked how her effort was progressing, and eventually wrote her a letter of recommendation. “Here, with little effort, I was able to have an effect on a person’s life,” Doty said. “To me, that’s an immense satisfaction.” Material riches had provided Doty with a consistent thrill, he said. But they were no match for the “helper’s high.” The coffee clerk is now in med school.

This article has been shared here with permission.

Bonnie Tsui is a frequent contributor to The New York Times and the Atlantic.

SHARE YOUR REFLECTION

4 Past Reflections

On Aug 25, 2014 Ziada wrote:

Thanks for this wonderful article! Lets all be part of what brings individual happiness and collective good. Forget about racism, as there is no such think as race within the human family - it is all an artificial construct to divide and rule and to exploit the vulnerable. We are all ONE human race and if we are to survive on this earth it has got to be give and take, live with love and compassion and let live and care for and look after each other.

On Aug 22, 2014 Kristin Pedemonti wrote:

Here's to being in service to each other and to seeing the opportunities in perceived obstacles. Though where we come from shapes us, it does not have to limit us. HUGS from my heart to yours!

1 reply: Joanne | Post Your Reply

On Aug 22, 2014 Brian wrote:

1 reply: Abdul | Post Your Reply

On Jun 17, 2024 Victor meich wrote:

Post Your Reply