The Island of Knowledge: How to Live with Mystery in a Culture Obsessed with Certainty and Definitive Answers

“We strive toward knowledge, always more knowledge, but must understand that we are, and will remain, surrounded by mystery.”

“Our human definition of ‘everything’ gives us, at best, a tiny penlight to help us with our wanderings,” Benjamen Walker offered in an episode of his excellent Theory of Everythingpodcast as we shared a conversation about illumination and the art of discovery. Thirty years earlier, Carl Sagan had captured this idea in his masterwork Varieties of Scientific Experience, where he asserted: “If we ever reach the point where we think we thoroughly understand who we are and where we came from, we will have failed.” This must be what Rilke, too, had at heart when he exhorted us to live the questions. And yet if there is one common denominator across the entire history of human culture, it is the insatiable hunger to know the unknowable — that is, to know everything, and to know it with certainty, which is itself the enemy of the human spirit.

The perplexities and paradoxes of that quintessential human longing, and how the progress of modern science has compounded it, is what astrophysicist and philosopher Marcelo Gleiser examines in The Island of Knowledge: The Limits of Science and the Search for Meaning (public library).

Partway between Hannah Arendt’s timeless manifesto for the unanswerable questions at the heart of meaning and Stuart Firestein’s case for how not-knowing drives science, Gleiser explores our commitment to knowledge and our parallel flirtation with the mystery of the unknown.

Artwork from 'Fail Safe,' Debbie Millman's illustrated-essay-turned-commencement address on courage and the creative life.

What emerges is at once a celebration of human achievement and a gentle reminder that the appropriate reaction to scientific and technological progress is not arrogance over the knowledge conquered, which seems to be our civilizational modus operandi, but humility in the face of what remains to be known and, perhaps above all, what may always remain unknowable.

Gleiser begins by posing the question of whether there are fundamental limits to how much of the universe and our place in it science can explain, with a concrete focus on physical reality. Echoing cognitive scientist Alexandra Horowitz’s eye-opening exploration of why our minds miss the vast majority of what is going on around us, he writes:

What we see of the world is only a sliver of what’s “out there.” There is much that is invisible to the eye, even when we augment our sensorial perception with telescopes, microscopes, and other tools of exploration. Like our senses, every instrument has a range. Because much of Nature remains hidden from us, our view of the world is based only on the fraction of reality that we can measure and analyze. Science, as our narrative describing what we see and what we conjecture exists in the natural world, is thus necessarily limited, telling only part of the story… We strive toward knowledge, always more knowledge, but must understand that we are, and will remain, surrounded by mystery… It is the flirting with this mystery, the urge to go beyond the boundaries of the known, that feeds our creative impulse, that makes us want to know more.

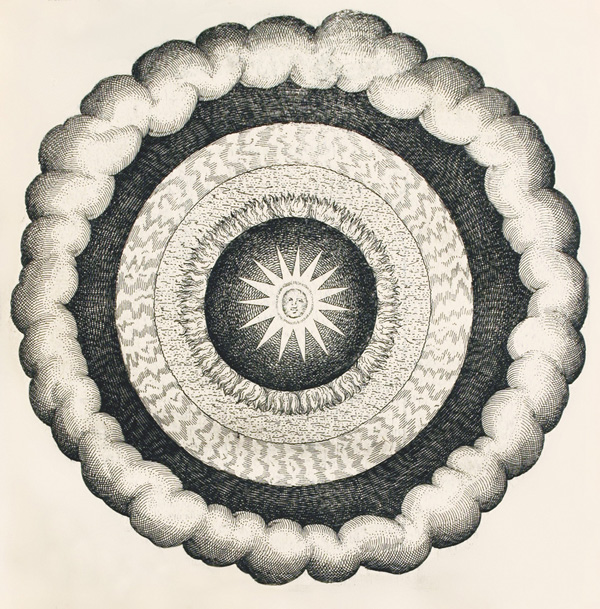

A 1573 painting by Portuguese artist, historian, and philosopher Francisco de Holanda, a student of Michelangelo's, from Michael Benson's book 'Cosmigraphics'—a visual history of understanding the universe.

In a sentiment that bridges Philip K. Dick’s formulation of reality as “that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away” with Richard Feynman’s iconicmonologue on knowledge and mystery, Gleiser adds:

The map of what we call reality is an ever-shifting mosaic of ideas.

[…]

The incompleteness of knowledge and the limits of our scientific worldview only add to the richness of our search for meaning, as they align science with our human fallibility and aspirations.

Gleiser notes that while modern science has made tremendous strides in illuminating the neuronal infrastructure of the brain, it has in the process reduced the mind to mere chemical operations, not only failing to advance but perhaps even impoverishing our understanding and sense of being. He admonishes against mistaking measurement for meaning:

There is no such thing as an exact measurement. Every measurement must be stated within its precision and quoted together with “error bars” estimating the magnitude of errors. High-precision measurements are simply measurements with small error bars or high confidence levels; there are no perfect, zero-error measurements.

[…]

Technology limits how deeply experiments can probe into physical reality. That is to say, machines determine what we can measure and thus what scientists can learn about the Universe and ourselves. Being human inventions, machines depend on our creativity and available resources. When successful, they measure with ever-higher accuracy and on occasion may also reveal the unexpected.

[…]

But the essence of empirical science is that Nature always has the last word… It then follows that if we only have limited access to Nature through our tools and, more subtly, through our restricted methods of investigation, our knowledge of the natural world is necessarily limited.

And yet even though much of the world remains invisible to us at any given moment, Gleiser argues that this is what the human imagination thrives on. At the same time, however, the very instruments that we create with this restless imagination begin to shape what is perceivable, and thus what is known, marking “reality” a Rube Goldberg machine of detectable measurements. Gleiser writes:

If large portions of the world remain unseen or inaccessible to us, we must consider the meaning of the word “reality” with great care. We must consider whether there is such a thing as an “ultimate reality” out there — the final substrate of all there is — and, if so, whether we can ever hope to grasp it in its totality.

[…]

Our perception of what is real evolves with the instruments we use to probe Nature. Gradually, some of what was unknown becomes known. For this reason, what we call “reality” is always changing… The version of reality we might call “true” at one time will not remain true at another.

[…]

As long as technology advances — and there is no reason to suppose that it will ever stop advancing for as long as we are around — we cannot foresee an end to this quest. The ultimate truth is elusive, a phantom.

Artwork by Marian Bantjes from 'Beyond Pretty Pictures.

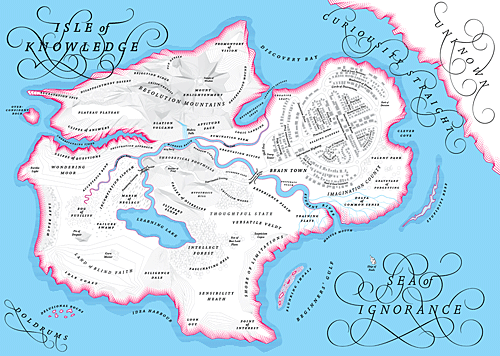

To illustrate this notion, Gleiser constructs the metaphor after which his book is titled — he paints knowledge as an island surrounded by the vast ocean of the unknown; as we learn more, the island expands into the ocean, its coastline marking the ever-shifting boundary between the known and the unknown. Paraphrasing the Socratic paradox, Gleiser writes:

Learning more about the world doesn’t lead to a point closer to a final destination — whose existence is nothing but a hopeful assumption anyway — but to more questions and mysteries. The more we know, the more exposed we are to our ignorance, and the more we know to ask.

Echoing Ray Bradbury’s poetic conviction that it’s part of human nature “to start with romance and build to a reality,” Gleiser adds:

This realization should open doors, not close them, since it makes the search for knowledge an open-ended pursuit, an endless romance with the unknown.

Gleiser admonishes against the limiting notion that we only have two options — staunch scientism, with its blind faith in science’s ability to permanently solve the mysteries of the unknown, and religious obscurantism, with its superstitious avoidance of inconvenient facts. Instead, he offers a third approach “based on how an understanding of the way we probe reality can be a source of endless inspiration without the need for setting final goals or promises of eternal truths.” In an assertion that invokes Sagan’s famous case for the vital balance between skepticism and openness, Gleiser writes:

This unsettled existence is the very blood of science. Science needs to fail to move forward. Theories need to break down; their limits need to be exposed. As tools probe deeper into Nature, they expose the cracks of old theories and allow new ones to emerge. However, we should not be fooled into believing that this process has an end.

I recently tussled with another facet of this issue — the umwelt of the unanswerable — in contemplating the future of machines that think for John Brockman’s annual Edge question. But what makes Gleiser’s point particularly gladdening is the underlying implication that despite its pursuit of answers, science thrives on uncertainty and thus necessitates an element of unflinching faith — faith in the process of the pursuit rather than the outcome, but faith nonetheless. And while the difference between science and religion might be, as Krista Tippett elegantly offered, in the questions they ask rather than the answers they offer, Gleiser suggests that both the fault line and the common ground between the two is a matter of how each relates to mystery:

Can we make sense of the world without belief? This is a central question behind the science and faith dichotomy… Religious myths attempt to explain the unknown with the unknowable while science attempts to explain the unknown with the knowable.

[…]

Both the scientist and the faithful believe in unexplained causation, that is, in things happening for unknown reasons, even if the nature of the cause is completely different for each. In the sciences, this belief is most obvious when there is an attempt to extrapolate a theory or model beyond its tested limits, as in “gravity works the same way across the entire Universe,” or “the theory of evolution by natural selection applies to all forms of life, including extraterrestrial ones.” These extrapolations are crucial to advance knowledge into unexplored territory. The scientist feels justified in doing so, given the accumulated power of her theories to explain so much of the world. We can even say, with slight impropriety, that her faith is empirically validated.

A 1617 depiction of the notion of non-space, long before the concept of vacuum existed, found in Michael Benson's book 'Cosmigraphics'—a visual history of understanding the universe.

Citing Newton and Einstein as prime examples of scientists who used wholly intuitive faith to advance their empirical and theoretical breakthroughs — one by extrapolating from his gravitational findings to assert that the universe is infinite and the other by inventing the notion of a “universal constant” to discuss the finitude of space — Gleiser adds:

To go beyond the known, both Newton and Einstein had to take intellectual risks, making assumptions based on intuition and personal prejudice. That they did so, knowing that their speculative theories were necessarily faulty and limited, illustrates the power of belief in the creative process of two of the greatest scientists of all time. To a greater or lesser extent, every person engaged in the advancement of knowledge does the same.

The Island of Knowledge is an illuminating read in its totality — Gleiser goes on to explore how conceptual leaps and bounds have shaped our search for meaning, what quantum mechanics reveal about the nature of physical reality, and how the evolution of machines and mathematics might affect our ideas about the limits of knowledge.

This article originally appeared in Brain Pickings and is republished with permission. The author Maria Popova is a cultural curator and curious mind at large, who also writes for Wired UK, The Atlantic and Design Observer, and is the founder and editor in chief of Brain Pickings.

SHARE YOUR REFLECTION

3 Past Reflections

On Mar 19, 2015 AnotherLover wrote:

1 reply: Stan | Post Your Reply

On Mar 20, 2015 bhupendra madhiwalla wrote:

Very good article. Iacocca of Chrysler motors used to tell his engineers 'don't try to develop a product 100% perfect otherwise you will be late to enter the market and lose it'. At the beginning of 20th Century many Physicists believed and said that everything whatever to be known is already now known. But then Einstein and Aspect Experiment and Heisenberg and many new revelations made us realize that 100% knowledge is not possible.

Post Your Reply