Quiet Justice

Meditating lawyers? It's no joke. Charles Halpern has been leading a movement to promote empathy and mindfulness in the practice of law.

When I tell people that I teach a class in law and meditation at UC Berkeley’s law school, I often hear snorts of disbelief. “It’s easier to imagine a kindergarten class sitting in silence for half an hour,” a friend said to me, “than two lawyers sitting together in silence for five minutes.”

Charles Halpern (left, foreground) leads a Qigong exercise at a retreat for 75 lawyers at the Spirit Rock Meditation Center in California.

Charles Halpern (left, foreground) leads a Qigong exercise at a retreat for 75 lawyers at the Spirit Rock Meditation Center in California. But the class is no joke. In fact, it’s part of a ground-breaking movement that has quietly been taking hold in the legal profession over the past two decades: a movement to bring mindfulness—a meditative, moment-by-moment awareness of our thoughts, relationships, and external circumstances—into the practice of law and legal education.

Judges have been meditating before taking the bench, and opening their courtroom with a moment of meditative silence. Lawyers in tense divorce negotiations have been more effective by maintaining a perspective of mindful reflection throughout the process. Courses offered at a dozen law schools have given law students an introduction to meditation—an effort to help them sharpen their legal skills and make them more effective trial lawyers, negotiators, and mediators. All these steps are part of a bigger effort to help these budding and established professionals cope with the stresses of law practice—a field that, regrettably, tops all American professions in instances of depression, substance abuse, and suicide.

To many people, it still sounds like an implausible connection, law and meditation. I know it has spawned a number of lawyer jokes. But my seminar has been oversubscribed for the first two years I have given it. Many of my students have reported that it has been one of the most important courses that they took in law school, fundamentally altering their approach to law study and their plans for a professional career.

And they’re definitely not alone; clearly, efforts to integrate a mindful perspective into the practice of law have been gaining momentum.

Now we’re approaching a milestone in this movement: On October 29, a remarkable gathering will take place at Berkeley’s law school, where 150 lawyers, professors, judges, and law students will come together to review the progress we’ve made. Over the ensuing weekend, they’ll meditate together and discuss the opportunities and challenges facing this movement and the legal profession as a whole.

My own introduction to meditation came when I was the founding dean of the City University of New York Law School. It was a highly stressful job, and I was not managing competing pressures well. A friend of mine, who had a well-established meditation practice and had been the founding dean of another law school, suggested to me that I might try meditation.

“What’s that?” I asked. He gave me simple instructions: take 20 minutes in the early morning to sit silently, looking inward, following my breath and watching my thoughts come and go. “What good will that do me?” I asked. He urged me just to try it and see if it helped me with the tensions of my job.

To my surprise, I found that these few minutes in the morning helped open up a place of stillness and balance to which I could return during the course of a harried and contentious day. If I knew I had a particularly fraught telephone call awaiting me, I would sit for just a few minutes, connect to my meditative center, and then turn to the phone call. It did not make everything go smoothly, nor did I handle every tense discussion skillfully. But it made a measurable improvement in my ability to be fully present in difficult situations and to respond more thoughtfully—less reactively—to challenging situations. Regrettably, I did not introduce meditation into our curriculum at that time, in large part because I did not yet see the relevance of meditation to the practice of law.

After CUNY Law School had graduated two classes and I moved on to become president of the Nathan Cummings Foundation, I had an opportunity to look more deeply at the connection between law and meditation through our grant program. The Foundation started supporting efforts to bring the contemplative dimension into mainstream institutions, and law was one on which we chose to focus.

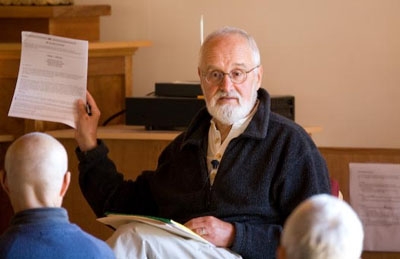

Halpern delivering a talk on the ethical obligations of lawyers at that same meditation retreat.

Halpern delivering a talk on the ethical obligations of lawyers at that same meditation retreat.The Center for Contemplative Mind in Society was created by the foundation and its partner, the Fetzer Institute, to carry out this mission. The Center held its first retreat for Yale law students and faculty members in 1997. It has held meditation retreats regularly in intervening years for students, lawyers, and judges, first on the East Coast and later at the Spirit Rock Meditation Center north of San Francisco. (Reports on these retreats are available on the webpage for the Center’s law program.)

As a co-leader of most of these retreats, my particular responsibility has been to teach the Chinese meditative practice of Qigong. In the early morning hours, as sunlight fills the meditation hall, I lead dozens of lawyers through meditative movements meant to help them center in their bodies, a sharp departure from their usual absorption in the analytic and cognitive processes of their minds.

Over the years, meditation practice has come to play a large part in the lives of many lawyers, as they have started to bring mindfulness into their own work as professors, public interest lawyers, judges, and mediators. Research has also shown that mindfulness is directly related to improving skills essential to a lawyer’s work: the capacity to listen fully during a client interview; the cultivation of empathy, which makes the lawyer a more effective advocate and counselor; the ability to remain focused and to see complex courtroom situations from multiple perspectives. And of course, mindfulness helps lawyers deal with the problem of stress and anxiety that overwhelms many of them and saps spontaneity and happiness from their professional lives.

As mindfulness becomes more widely diffused and embedded in legal education and practice, we can anticipate that the core values cultivated through mindfulness practice—empathy, compassion, a sense of interconnection and impermanence—will be reflected in the functioning of lawyers and courts, and in the substance of legal doctrines.

The October conference is a milestone in the development of this movement. It will build a foundation on which the next generation of developments can take place, spreading the practice of mindfulness more widely, deepening lawyers’ satisfactions with their work and lives, and improving the quality of the service that they offer to clients. Over time, mindfulness could make a significant contribution to improving the quality of justice in individual courthouses, in the United States, and in the world.

Charles Halpern, JD, is currently a lecturer at the University of California, Berkeley School of Law, where he teaches its course on law and meditation. He is also the author of Making Waves and Riding the Currents: Activism and the Practice of Wisdom. This article was originally printed by Greater Good Science Science Center.