First, the Work of Paying Attention to the World

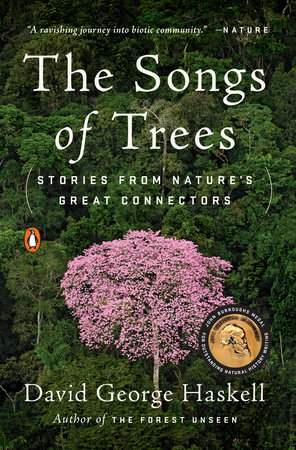

David George Haskell is an ecologist and evolutionary biologist whose work is located at the thrumming intersection between science and poetry. He integrates rigorous research with a deeply contemplative, immersive approach. His subjects are unexpected and unexpectedly revelatory. His widely acclaimed, Pulitzer-finalist book, The Forest Unseen, chronicles the story of the universe in one square meter of forest ground in Tennessee. His follow-up book in 2017, The Songs of Trees, encompasses a study of humanity's varied roles within biological networks, as heard through the acoustics of a dozen trees around the world, which he visited regularly. David's innovative approaches to teaching and fieldwork, his radical commitment to a whole-bodied study of the natural world, and his remarkable lyrical gifts have yielded a lush and Illuminating body of work that returns us to our place in the web. As one reviewer put it, "With a poet's ear and and a naturalist's eye, Haskell re-roots us in life's grand creative struggle and encourages us to turn away from empty individuality. The Songs of Trees reminds us that we're not alone and never have been.

David George Haskell is an ecologist and evolutionary biologist whose work is located at the thrumming intersection between science and poetry. He integrates rigorous research with a deeply contemplative, immersive approach. His subjects are unexpected and unexpectedly revelatory. His widely acclaimed, Pulitzer-finalist book, The Forest Unseen, chronicles the story of the universe in one square meter of forest ground in Tennessee. His follow-up book in 2017, The Songs of Trees, encompasses a study of humanity's varied roles within biological networks, as heard through the acoustics of a dozen trees around the world, which he visited regularly. David's innovative approaches to teaching and fieldwork, his radical commitment to a whole-bodied study of the natural world, and his remarkable lyrical gifts have yielded a lush and Illuminating body of work that returns us to our place in the web. As one reviewer put it, "With a poet's ear and and a naturalist's eye, Haskell re-roots us in life's grand creative struggle and encourages us to turn away from empty individuality. The Songs of Trees reminds us that we're not alone and never have been.

What follows is the edited transcript of an Awakin Call interview with David George Haskell. You can listen to the full audio recording of the call here.

Pavi Mehta: Could you share with us some of the formative influences in your early life that led to what seems to be a lifelong love story with the natural world?

David George Haskell: I think we're all in a deep relationship with the natural world. Of course, we're learning these days from ecological and evolutionary science what philosophical traditions have been saying for thousands of years: that there isn't really a division between humans and the rest of life's communities. And that realization comes to many of us through multiple means. For me, it comes partly through being an evolutionary biologist and partly from early experiences.

I remember quite distinctly spending many afternoons on the edge of a little pond, poking around and looking at the little creatures that lived there. That pond became a place for study and reflection on the water, the watery creatures, the algae, and so on. All those things seemed to be separate from an intellectual study of the world. But as I pursued my college education and then became a teacher, I came to see more and more that these were things were interconnected to one another and that we were telling different parts of the same story. So, as a child, I did have connections to other species and to places that were not dominated by human effects, but I also had the privilege of growing up with a family that included a number of biologists, people who could identify the birds and the flowers, and point things out to me that I may have otherwise just walked right on past and never opened up to.

Pavi: In The Forest Unseen, you ask, "Can the whole forest be seen through a small contemplative window of leaves, rocks, and water?" And that's a remarkable question. Was this approach of studying the macrocosm through the microcosm something that came very naturally to you or something that you arrived at over time?

David: That project was a place where I tried to integrate different strands of my life. I tried to take the parts of my life as a teacher and scientist and understand those a little more deeply through my own research and meditations with the natural world. For many years, these were all present in my life, but they weren't really interconnected in any particular way.

So when I undertook the work that led to this first book, I tried to draw those strands together to ask, "What would happen if I took a meditative approach to just one tiny patch of forest?" I went to the same square meter or forest over and over again, and gave my attention to it through a year, and, now, through many years.

While there, I began to ask questions that came from my life as a biologist, a naturalist, and a teacher, not to divide these different parts into different segments, but to unite them into one project. One of the big messages from contemplative traditions is that the contemplation and study of what at first seems to be small (it might be attending to the breath, directing one's gaze again and again to a particular piece of visual art, music, prayer, or poem), unfold more layers of the story and experience to us, so that we see perhaps further and deeper by restricting the gaze.

I applied this approach in the forest by returning again and again to a little patch of forest and trying to pay attention to it and tell the stories of that forest rather than trying to grasp the ecology through shallow attention to thousands of places.

Pavi: There's almost a radical simplicity to this study. There's no fancy equipment required; you're just being present. Can you describe how you trained your attention and tell us if there were any practices or techniques you were following in the forest?

David: I restricted myself by design to simple methods, and my rules were to just show up and try to open my senses to the place. I had a notebook, a pencil, and occasionally a small hand lens or a pair of binoculars. What that forced me to do in the forest was to finally awaken the sense of hearing and become aware of the different qualities of light as the day proceeded into night, and as the days changed through the seasons. The changing-light environment is of critical importance to the animals and plants in the forest, but it's very easy for humans to wander through and not pay attention to that. Then the sense of smell reveals all kinds of hidden stories, particularly in the microbial world because, although we can't see microbes, we can smell many of them just by drawing close to the leaf litter or to a lichen-covered rock.

So my method was quite simple, but it was also challenging because we are all well-trained to turn off our senses. In fact, we need to turn off many of our senses in order to focus on one thing at the time, but as we get better and better at focusing, we also need that practice of un-focusing, of reorienting the senses back to the world around us. So it's a little bit like inhaling and exhaling: both are necessary by themselves, but we need both to draw the breath of life. Likewise, we need practices that allow us to devote our attention with great care to a small number of things, particularly in a world where we're beset by propaganda, flashing lights, and sounds. But as we erect these shields, we also need a time to take the shields down, open the senses in an open-ended and an unfocused way, and wake up to the world around us.Pavi: I love that you use the phrase “awakening the senses.” For some of us reading your book, it's amazing to be exposed to the nuances that you're able to tune into. But it can feel a little bit hopeless for some of us as we reflect on the fact that we are missing all of that as we walk through the world. I wonder if the rest of our senses kind of go to sleep because we are so visually biased. Was there a particular sense that you found hard to awaken and then felt a thrill when it did open up?

David: Yes, that happened with all of the senses. Even though we are a visually oriented species, we often take only a glance at things; we don't really pay attention to the details. For example, imagine a tree on a city street. We take a glance at it and just label it with the name. "Oh, that's a plant. That's a tree." And by labeling, we cut ourselves off from a deeper visual experience. But by returning again and again to the same tree, we can come to see all the visual particularities: What is the texture of the soil around the base of the plant, and how does that texture differ as one moves away from the plant? What is the bark like? How are the leaves oriented? Is each leaf the same, or does each leaf have its own character? How are the features and orientations different from yesterday?

So with the sense of vision, one of the things that really woke up for me over the first year was the extent to which the palette of light, by which I mean the range and tonality of colors, changed radically through the year. For example, in midwinter, all the leaves were down, and, though it was quite gray and brown, the light coming from the sky was full of all kinds of colors. When animals came past, I could see them in the full glory of the colors. Then, in the summertime, the leaves formed a complete canopy that allowed only yellow-green light through. So, something that appeared dull and cryptic in the summer could look bright red in the autumn. And I had an incredible sense of opening up, like a weight was being lifted, and somehow the sense of vision was transformed, almost like new dimensions had been added.

By paying attention to all of the senses, I learned many new things. I know most of us go through our lives with the senses totally turned off; how many of us today attend to the details of the odor of the food that we're eating or of all the different rooms that we walk through, or how the smell and even the taste of the air changes as we walk down the street or go into our homes? If the smell is very obvious, we notice it, but mostly all those subtleties enter our nose but don't enter our consciousness. But all of that is available to us if we just start to pay attention.

Pavi: That's remarkable. And is it something that you turn on and off, or is it something that, whether you're in the subway, a conference room, or the forest, you're taking in all of that information?

David: I think it's both. I think most people who have engaged in these kinds of practices would agree that it changes how you relate to the world. You become more aware, for example, of sounds, smells, and changes in light. But you have the ability to turn away from that and to free yourself by just being reactive to them. In other words, you restore agency to yourself when you choose to focus on something else.

When we do attend sensory inputs, hopefully it is without judging: to just note and appreciate them but not react. Often we hear a sound and immediately judge it. For example,"That is a pleasant sound. I like that!” Or: “That's a nasty sound, and it makes me angry or it makes me feel that I don't want to be here." Whereas these are all just different kinds of vibratory energies present in the world around us, and we can control how we react to them. And one of the practices that I use in environments I would otherwise find quite unpleasant is to do a little sensory meditation: run through the senses, list off the various impressions that are coming to me from the outside, and then become aware of how I'm reacting to them internally. And through that, I can realize that the place I previously judged as being 100% unpleasant has all kinds of interesting layers to it and that it’s possible for me to be there without being quite so annoyed or judgmental.

Pavi: Sounds like incredibly valuable life skills to have. Is it true that the book came out of listening to birds?

David: The book is a confluence of several things that I thought were interesting and important, and one of them indeed came from listening to birds. For many years, I've taught a course in ornithology—the scientific study of birds— and part of what I do there is ask students to identify many of the local species by sight and sound. To help with this, I invite students into some acoustic meditations, where we first name all the sounds that we can hear. Then we describe them. Finally, we sit in the physical presence of the sound without any further naming or describing. It helps students to become more aware of the sounds birds are making and to attune their memories to the rhythms of birds.

But in doing that, I started to notice all the trees making different sounds too. For example, the sound of the wind in a white pine is very different from the sound of the wind in a sugar maple or red oak. So each tree has its own sound, its own wind song, if you like, evoked by air moving through its leaves and branches. Those different sounds allow us to appreciate and interact with trees with a different sense from what we normally do.

I realized that part of the sound was the tree’s interaction with its environment. This includes interactions with people, and those interactions take very different forms in different parts of the world. In the Amazon rainforest, people's relationship with trees is different from those outside the gates of Jerusalem or on the streets of Manhattan. And I sat with trees in each of these places to try to discern what their sounds were telling me about how people and trees were interconnected.

Pavi: I'm going to quote a little bit from The Songs of Trees. You say, "To claim that forests think is not an anthropomorphism. A forest's intelligence emerges from many kinds of interlinked clusters of thought. Nerves and brains are one part, but only one, of the forest's mind." Can you explain what you mean by that?

David: Yes, so what we have learned over the last few decades from ecological, evolutionary, and plant physiology studies is that when we walk into a forest we're not walking into a place that is full of separate interacting individuals.That was the old view of ecology. Instead, we now know that we're walking into a living network, a place where every creature exists only through relationships with others. For example, a tree is not just one species or one individual but a living community. Every leaf on a tree has hundreds of species of bacteria and fungi living on it. Without them, the leaf would get overrun by pathogens and be unable to protect itself from drought. Likewise, the roots of trees are also living communities, interconnected with fungi, bacteria, and others below ground. And so the life of the tree emerges not from individuality but from network relationships. And that tree is therefore connected to the trees next to it and to the trees further on. It is connected to all of the animals and plants within the forest. A forest, grassland, garden, or even a city street is not a collection of individuals; it is a living community.

Network relationships produce a kind of intelligence within the forest, just as our brains are made out of interconnections between neurons that establish their reality only through connection with others. There’s an incredible level of complexity of connections through billions and billions of bacterial cells in just one teaspoon of soil. So, think about that: one teaspoon of soil in your hand contains as many bacterial cells as there are humans over the entire globe. Of course, the human brain is a very centralized structure. In the forest, the intelligence, thought processes, memories, and decision-making are a lot more diffuse throughout the entire network, though they do include animal brains.

Pavi: You talk about the contradictory creative duality in nature. Are we atoms or networks? We are neither and both, and it's not just a question of metaphor but the fundamental nature of life. One of the most provocative realities that the book surfaces is that the fundamental unit of biology is not the self but the network and that the self is a society. Especially in today's modern world, it runs so counter to our views of self, and I wonder, as you have explored this so deeply, has it shifted your perspective on our place as Homo sapiens?

David: Yes, absolutely. Biology has been dominated now for a hundred years by an atomistic view, where the fundamental reality was that we are separate individuals and that the atom is the fundamental unit of life. That model has a certain power to it as it helps us explain certain aspects of life. But it's limited and incomplete. A complementary model is that life is made from network relationships.

Each of these models is a simplification; neither one can fully encompass all the different realities of life. And yet our thinking and language have been dominated by the atomistic view, and now we need to make space for a view that the individual is in fact an illusion, a temporary manifestation of relationship. So if that indeed is the case, or at least is a good model for a large part of the living world, that does change how we think about ourselves as human beings.

What is true for a tree is also true for an individual human. Our bodies are made of dozens and dozens of interacting species, including bacteria and fungi, and without the interconnections among all those members of the community our bodies don't function. But it's also true at the level of culture, which is an extension of that network. Everything from the fundamentals of language to very sophisticated intellectual ideas emerge from connections with other people. So the brain is a temporary locus, a temporary manifestation of a broader phenomenon, and that phenomenon is a culture that connects across space and time.

One of the more remarkable inventions of life is human culture, particularly written culture. For example, reading a piece of literature that was written a thousand years ago can connect our mind directly to the mind of someone whose body has been dead for a thousand years but whose words are still alive because they are being reborn within us. And that all sounds very mystical but I mean it in a very physical, direct way, in that those ideas that existed in human minds passed through the generations from one nervous system to another through externalized connections that we call culture and literature. And so any particular book is one tiny portion of that larger living network.

The the other really important dimension to this is that if the nature of life is a networked community, then that changes how we think about ethics, particularly environmental ethics. None of us are alone in this, and all of our actions do indeed affect all other members of the network. So rather than asking, "What rights and responsibilities do I have as an individual?," the question might then be, "How could this community thrive, and what relationships are most important?” Some of the answers may be similar to those derived from individually based ethics questions, but I think that we can shift the questions we ask and the ground from which we answer them if we believe ourselves to be part of the living network that transcends any particular individual.

Pavi: What are the other potential implications of how this awareness could manifest in the world?

David: One of those manifestations might be a different understanding of what beauty is. We tend to think of beauty as rather ephemeral and subjective and not really rooted in anything we can scientifically or ethically analyze or use for policy recommendations. If instead we think of beauty as emerging from a process in which all these different parts of the network connect together through our bodies, senses, intellect, and emotion, a sense of deep beauty emerges that gives us a different ground on which to stand as we make ethical determinations. I think there's a connection between a sense of aesthetics and a new understanding of what biology is telling us about the nature of networks in life. Those two things are connected, and beauty forms a bridge between an understanding of the world that is rooted mostly in scientific analysis and one that can connect to questions of ethics and to finding the good in life.

Pavi: Your work in the forest brings up images of greenery, the wind going through your hair, and tuning in, and yet you were bitten, stung, scratched, and scorched! Can you speak a little bit about the roles of those polarities?

David: Living networks are not places of benevolence. They're not places where it is all joy and good feeling. Instead, living networks are the places where both cooperation and conflict are part of what animates life. What drives evolution is the tension between cooperation and conflict that is present in any set of relationships.

The traditional way in which biologists have talked about this is that it's a very competitive world, and that evolution favors those creatures who look out for themselves and have a very individualistic outlook on things." Well, it turns out that's not at all the case. Every major evolutionary transition, from the origin of life, to the development of large cells, to the evolution of of large complex organisms like humans and trees, to large sophisticated ecosystems like coral reefs, grasslands, and forests, have all taken place through organisms that first have separate lives and that then join together in cooperative relationships in order to deal with the rigors and difficulties of the environment. And so it turns out that cooperation is one of the great emerging themes of the grand drama of evolution. So, that's one of the things that I see when I stand back and look at the larger picture.

Pavi: What's humbling and powerful is the de-centering of the self in your writing. I wonder if that is something that was with you when you walked into the writing, or if it gradually unfolded for you.

David: What I tried to do was to listen to the stories of species by being present and reading what other people had written about them. I tried to present those stories with me in background because I think the forests are a lot more interesting than I am.

One of the themes that emerged from the book was the limitations of any one organism’s perspective, whether it be mine or a tree’s. Paradoxically, by studying with a focused lens one tree on the street corner in Manhattan over several years, I came to understand a lot about that particular city. So there's a paradox that when an individual fades into insignificance, we truly come to know that individual and then come to see a large portion of the ecosystem.

Pavi: One of the things you talked about was taking approaches from contemplative traditions into the forest. And one of the things within contemplative traditions that's often surfaced is tuning into the changing nature of reality, the impermanence of life. From the human perspective, impermanence often comes with a sense of loss, suffering, and pain, and I'm wondering how your experience as a mortal has been informed by your perspective as a biologist.

David: One of the trees that I returned to again and again for my second book was a very large ash tree, which had fallen down and was starting to decompose. I came to realize that the line between life and death for trees is actually not so clearly drawn.The living tree is a being that catalyzes and regulates conversations in and around its body, and after death those processes continue on it. It continues to be a member of the community, and, in the case of a very large tree in the temperate forest, that process can go on for decades.

So when that large tree falls, there is an ecological analog of grief in the forest: species whose lives are very tightly bound up with that tree lose something, sometimes very important things. But, in another way, the network is reconfiguring itself through that tree's death​,​ and new life is emerging from that.​ I think that's also what we're contributing as we pass through this life. And I don't want to draw the analogy too tightly here, but I do think that dying fallen tree helped me see my own life and the lives of other people in a way that made me think that human culture and life are a lot like the processes within the forest, in which new creativity emerges from loss.

Preeta: Do you see any shifting today away from biology’s historic focus on the individual?

David: I think within biology there is a significant shift underway, giving us new ways to think about the world. The same is true in other areas, such as economics. Adam Smith's idea about the foundation of economics being interacting free individuals is a very powerful view, which in some ways freed people from economic systems that were dominated by the control of a small number of powerful individuals. And, of course, a downside is that it may neglect the networking and cooperative natures of economic action. I think that we are right in the middle of an incredible paradox. We do have a great deal of emphasis on the individual, whether that individual is an economic entity (a consumer of goods) or a political entity (a voter). And those individuals are becoming more disconnected because we can lead separate lives in the digital era, and yet at the same time our economies are becoming more mutually interdependent, so that what happens in London affects what happens in Beijing within seconds. Centuries ago, although there were connections among the economies of the world, they were much slighter and took much longer to enact. So the power and manifestation of networks are so much more obvious these days. My hope is that we come to think about our lives as members of communities more and de-emphasize the narrative of the individual being the only possible way of thinking about the world.

Comments and Questions from Listeners:

Kozo from California: I wanted to ask you about the idea of vibration, whether you're talking about auditory, feeling, or even seeing things through the eyes. Did you ever tap into what people call a “universal vibration”? Like a divine vibration or one that you can't really identify?

David: I don't know if I'd call them vibrations because I think of a vibration as an acoustic phenomenon or one that comes through my hands when touching a surface. But I sensed processes that far transcend what the human senses and imagination can grasp. And as a biologist, I would say the most important of those is the sense of the deep time of things. Tme still has a great deal to unfold, and I occupy an unimaginably small position within that arc of time. It's really an extraordinarily humbling feeling. So, things that really struck me were causing resonance, like a chord within me, and that was the one that was the most awe-inspiring and hard to put a finger on it. I'm struggling for words now, to even describe what that feeling is like.

Gayathri: As a trained scientist myself, I am aware how much scientific training emphasizes objectivity and reproducibility, thereby diminishing the value of a personal subjective narrative. I'm curious how you managed to keep the unique voice and perspective of yours alive through years in academia. Were you supported by any mentors in this quest? How has it been received by colleagues and students?

David: Too much emphasis on objectivity diminishes both the practice of science and our lives as people because everyone comes to that objective practice through a subjective path: the path of our own lives and our own sensory impressions. What I've tried to do in my writing is to tell those larger stories that often emerge through objective scientific analysis through a very subjective lens, the lens of my experience of these particular patches of land and particular trees. So, I'm trying to integrate those, and I think that integration is absolutely necessary for us to be fully human. In addition to the objectivity of science that helps us see big trends and patterns in the world and understand the functioning of cells and other amazing and important things, we also need subjective experience to understand why this is important, what it means to us, and what the limitations of the scientific method are. The scientific method is really great at answering a certain number of questions, but those questions are limited.

Science cannot provide answers to ethical questions. There is no experiment that can decide between right and wrong. Ethical discernment emerges from subjective experience and from conversations within a community that has developed over the millennia. And so to live well in the world, I think we need both an objective and subjective experience.

In terms of mentors, I've had many teachers who have conveyed to me the objective knowledge of their disciplines through the lens of their own lives and then made these things relevant to me. My teachers also came from books, people like Annie Dillard, E.O. Wilson, Henry Beston, and other folks who who tried to understand the world through the lens of both objective thought and subjective experience.

Mish from New York: When I was in California, I went for a walk through Muir Woods, which was a truly beautiful experience. I noticed what looked like faces on some of the trees. There was one tree in particular: a huge ancient redwood, and it looked like the face of a wizened old man. What are we seeing when we see these faces?

David: I haven't seen these particular trees, so I can't provide a full answer. But from my experience, I would say we're seeing two things. We are seeing the character of that particular tree revealed to us, so that those crevices in the bark and those twists and turns and so forth are revealing the story of that tree to us, just as, say, the shape of a person's face and the wrinkles tell us something of that person's life. And then we're also seeing our own psyche reaching out into that place and trying to understand what this place means for us. And so the tree's narrative meets our narrative. And then it manifests in a particular image, in a particular experience of that moment. I would guess that other people might see something different in the bark. What another sees is not less true; it's just emerging from a different connection between that person's relationship with the tree and tree's narrative.I would invite you to continue that process. If you're in Brooklyn Prospect Park, there are some extraordinary trees. I’m thinking of some of the Turkey Oaks down by the well house. The idea is to gaze even when it doesn't seem to be something that is immediately attracting one's attention and to see what emerges from this particular tree’s bark over the weeks and years.

Adonia: As a designer, I've been contemplating my role in the community, and I was wondering, since you have gotten so close and intimate with trees, what is your view on cutting down trees to create furniture?

David: Yes, of course we all use wood. As a writer, I write upon sheets of flattened cellulose that came mostly from trees. And one of the striking things that I discovered in my conversations with other people about trees is a notion that comes from Japanese carpenters. They say that if you cut the tree you need to give that wood a second life that is as long and as beautiful as the first life of the tree. If, for example, you cut a tree that is five hundred years old, you have an enormous amount of responsibility to create something that will last for at least 500 years and whose purpose and use in the world will be at least as noble as the purpose and use of that five hundred year old tree. Now if you cut the tree that is just 10 years old, the responsibility is to make something that will have a good and noble purpose, a beautiful purpose for at least 10 years. And I thought that was a rather interesting and helpful way of thinking about our relationship with trees. There is indeed a place for humans to interact with trees in the way that uses the tree.

But the ethical impetus is to use the tree well. We use trees in many ways, even in our inhalations. When we breathe in, we're using oxygen that trees have produced. That's a way of using trees that doesn't diminish the tree itself. We also harvest nuts and cut the trees down and let new trees grow. And then there are more extreme ways: cutting the trees down and covering them with asphalt so no other forest can can grow there again for perhaps hundreds of years.

Each one of these ratchets up the intensity, and I think the underlying ethical question is the same: if we are taking a life, what do we then create from that and how does that measure up to the destruction that we have wrought in the world? I think a good future for humanity is going to involve changing our relationship with trees, and part of that involves not using wood products in excess of what we need, and not doing things like making disposable products from five hundred-year-old trees, which, regrettably, is happening to this day.

Margie from New Jersey: Kahlil Gibran wrote, "Forget not that the earth delights to feel your bare feet and the winds long to play with your hair." So, this is at least partially biologically true, no?

David: Absolutely, that's a deep part of our being living creatures here. We, as a human species, have been around for 200,000 years. And before that, our non-human ancestors were feeling the ground under their feet and the wind in their hair. So when we feel those things, we are awakening to a very deep part of our being.Preeta: In ServiceSpace we focus a lot on the idea that small acts at the individual level can have ripple effects on the network. I wonder what you think about that as a view of social change. Is it enough, in your opinion, when we're talking about issues like climate change?

David: So we never know what will be enough. We don't know the future. What we do know though is that, in network communities, what seem like small actions can sometimes have enormous consequences for the network. But from no particular part of the network is that predictable. So I think that one of the main lessons from studying networks within forests and human social change, is the great unpredictability of cause and effect.

It is really important for any kind of social change to include the linking up with others in the network. And through doing that, we open all sorts of unimaginable possibilities for the future. If we do not put effort into forming those relationships, then we're not making full use of the network. We're not even really inhabiting it in the fullest possible way, so I do think social change emerges through all sorts of network connections. Whether that will be enough to, for example, tackle the great questions of poverty, inequity, climate change, and extinction, we don't know. But what we do know is that if we put no effort into these, no solutions will be found.

Wendell Berry has a an interesting perspective on this. He says it's really not for us to decide whether we should be hopeful about affecting the change that we want to happen in the world. It's up to us to try, and it's up to the future to decide whether we are successful or not. We should get down to the work of first paying attention to the world and then discerning where our right path forward is within the community.

Preeta: You've received a number of teaching recognitions, prizes, and honors, and I'd love to hear about your teaching methods that have been innovative and have brought students into more of these contemplative practices.

David: I think that first-hand experience is very important, so whatever we're discussing in class, I very much want the students to be directly engaged with all of their senses. I have taught a course on hunger and food, in which students grow food in the garden and work in the local food bank. Through those experiences, they come to understand truths that are not available just by picking up a book and sitting in the seminar room.

I also ask them to take into their lives periods of silence, of directed listening, and of attending to their senses. I tell the students, "There's no particular outcome that I'm looking for here. What I want you to do is to have this experience of contemplative engagement with yourself and with the world and then to reflect on that experience and see what it means for you." And for some students, it may not have any particular meaning at this moment in their lives, but for many I do think it offers additional dimension to their academic studies and, more importantly, to the studies of their own psyches, of their own places within the community, and within their own narratives.

Preeta: Can you talk a little bit about how work on your second book might have shifted you? What changes happened in you as you worked for years looking at those twelve trees?

David: With the second book, I wanted to place myself in a number of spots where it seemed that what we call nature wasn't really present (in the middle of cities and industrial zones and so forth). The first book had been set in an old growth forest, and I wanted to swing the pendulum of experience the other way and see what I might learn from that.

I came to understand that that the city street has many ecological stories present, just as an old growth forest does, partly because the city street was created by people, who are members of the ecological community. There is no sharp division between humans and everything else. That is the insight from Darwin and ecological science: division is an illusion. So that emerged for me as a very key insight, understanding how deep the connections are between people and trees and other species, even in places where those relationships don't seem to be present on the surface.

Pavi: You wrote in an article recently, "A necessary complement to the objectivity of science is the subjectivity of experience, an enthusiastic openness to the lives of other species. The timing of tree blooms on city streets, the calls of frogs in the wetlands, or the arrival of migratory birds is an act of resistance to deceptions and manipulations that work most powerfully when we're ignorant. ‘Post-truth’ does not exist in the opening of tree buds.”

Preeta: So beautiful. David, how can we as a community support your work?

David: I would close with an invitation for everybody to find a tree, a little corner of a neighborhood, or a patch of forest and choose that as a place you'll return to again and again with open senses. To try to listen to the stories of that place without any expectation of what you're going to find there. Return again and again, and turn on the sense of curiosity. Really befriend that place. And then extend that friendship over weeks, months, and perhaps years, and see where that relationship takes you. That would be my hope: both for my continuation of those processes and for other people to invite those experiences into their lives without the predetermined notion of where that experience is going to lead.

This transcript was syndicated from Awakin Calls, and edited by Ginger Shoup. Ginger is a volunteer copyeditor for ServiceSpace, a mom of two, and a curious explorer of nature and humanity.

On Mar 23, 2019 Patrick Watters wrote:

As an ecologist and evolutionary biologist myself, yet also “en Christo”, I resonate here on both an earthly level as well as cosmic level. Conversations with my sons, the younger a biologist like me, the older an astrophysicist and cosmologist, affirm and deepen my sense of a universal “family”. As a poet/mystic of Celtic and Lakota origins, I say mitakuye oyasin (Lakota), hozho naasha doo (Navajo) — all my relatives, walk in harmony. }:- ❤️ anonemoose monk

Post Your Reply