Burned Pages Don't Lie: A Genealogy Search

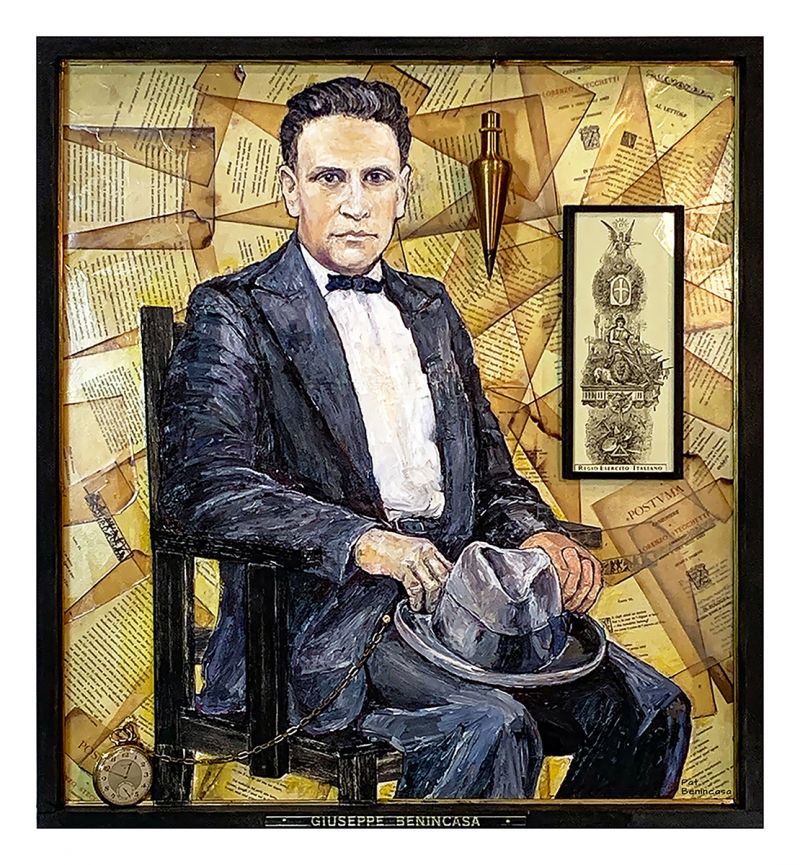

A 1924 Postcard Photograph of Giuseppe Benincasa, taken in Canada

A genealogy search can yield many things and go down many paths, but at its core, it is a story waiting to be told and a person to tell it.

My grandfather, Giuseppe Benincasa’s story began 10 years ago, when my cousin Helen Salfi Gorday gave me a charred book of Italian love poems. She said that it belonged to our grandfather and that I should have it.

The book is, “Postuma” by Lorenzo Stecchetti, an author who didn't exist, yet became a leader of the Veristi Literary movement in Italy after it was published in 1877. The Veristi were the anti-Romantic, Bohemian new realists who brought fresh language and energy to poetry. The real author, Oilindo Guerrini, created this suffering, doomed cousin, Lorenzo Stecchetti by beginning the book with a letter concerning his obituary. The country was scandalized by his ruse, and the book went into multiple printings. At this time poetry had been in a lull and the Veristi ignited public interest in poetry. What was he doing with this book and why was it burned?

Where He Started

I have a postcard photo (see above) with a 1924 stamp on the back with him seated, nicely dressed holding his hat with a glimpse of a prosthetic left hand. There he sits in sepia silence staring beyond time and place. I ask him, “Who are you and what happened to your arm?”

To answer this question, it is important to understand Calabria- a revolving door of invasion, earthquakes and foreign domination.

Giuseppe Benincasa was born in 1882, in Mangone, a small village 13 miles south of Cosenza in Calabria. He was the oldest with two brothers and a sister.

Calabria, in the “toe” of the “boot” of Italy, has rugged terrain with three mountain ranges that separates Calabria from the rest of Italy. According to Wikipedia, human presence in Calabria is recorded from around 700,000 BC. In antiquity, a tribe of Greek “vine cultivators” settled there in 1500 BC. “Originally the Greeks used 'italoi' to indicate Calabrians and later it became synonymous with the rest of the peninsula. Calabria therefore was the first region to be called Italia.”

From the Middle Ages on, Calabria was invaded by Visigoths, Byzantines, Lombards and Saracens. By 1060s in came the Normans, then the Swabians. By the 1400’s the Aragonese took control until the arrival of the Spanish Bourbons in 1735. They held it until a brief French interlude by Napolean from 1808 to 1815. In between the Bourbon and French occupations came the mega destructive earthquake of 1783.

Then back came the Bourbon Monarchy who competed with wealthy landowners to oppress the people. Through all of the invasions, natural disasters, malaria outbreaks, and harsh conditions, the Calabrese have endured with their resilient, stubborn spirit intact and earning the name “hard heads.”

By 1860, Garibaldi and his Redshirts liberated the South (the Mezzogiorno) from the Bourbons and the newly unified Kingdom of Italy was formed.

After 1861,the Post-unification South did not reap the benefits of this newly united Italy. Unlike the North which developed roads, canals, railroads, and industry, the South, which was held in feudal bondage by wealthy landowners and the Bourbon monarchy had few roads, hardly any canals, sparse railroad lines and a 70% illiteracy rate. According to Denis Mack Smith, Even the Deputies of the Mezzogiorno voted against money for education because “ an educated population would demand changes that would threaten the power of the traditional elite.”

The North viewed Southerners as barbarians in need of domination vis a vis troops. They conscripted young men into military service and brutally taxed people who already were living in dire poverty, “la miseria,” dealing with famine, malaria, brigands and sparse economic opportunities.

So began the Calabrese Exodus from 1901 to 1914 with Giuseppe among them.

Going To and From

In March 1906, Giuseppe married Gaetana Mauro, who some say was “the prettiest girl” in Mangone. A few months later, in May, he, his brother Antonio and two Mauro brothers-in-law sailed from Naples to New York.

The Ward America Line passenger list has Giuseppe, age 23, a farm laborer who can read and write with $30.00 in cash. His destination was Graven Hurst, Ontario Canada. Many Italians chose work destinations based on family or neighbor word of mouth.

Being new to genealogy work, I went all Hansel & Gretel to follow a path of breadcrumbs (paper trail) to make my way through a forest of unknowns. Here is where it gets dicey, because as much as I want to make assumptions, or jump to conclusions from my modern vantage point, I had to constantly put myself in his shoes to see where he would lead me.

Following the paper trail of passenger ship lists, border crossings, Italian Royal Army documents and Canadian Naturalization papers, I was surprised at how much he got around!

He and Antonio went to Montreal in 1908. In 1910, his son Bruno was born in Mangone. In 1914 he returned to New York on the SS Walther, and then he and Antonio went to Vancouver, British Columbia. Back to Italy, where his daughters Teresina then Marietta were born. Their son, Bruno died at age 6. Giuseppe served in the Royal Italian Army from 1916 to 1918.

After getting a Certificate To Emigrate, in December 1919, a third class boarding pass on the SS Cretic of the White Star Line says that Giuseppe Benincasa, age 37, having purchased a whole seat (not a ¼ or ½ seat) paid 40 cents to bring a small valise, left midday from the Port of Naples to Boston and he was entitled to “No. 3 food rations.”

He went back and forth from Italy, several times, but in January 1920, he and Gaetana arrive in Buffalo New York, and their son Francesco (my dad) was born in Mangone that same year.

The 1921 Canada Census shows the family living in Thorold, Ontario Canada with his brother Antonio. It also lists Giuseppe as a “loody man” working on the Welland Canal. By 1923, the family became naturalized citizens of Canada.

Canada and Now It Gets Personal

Before I go any further, our family referred to our grandparents, Giuseppe and Gaetana as “Papaco and Mamaco.”

When starting this genealogy search a few months ago, I began a Papaco Journal where I would write letters to him after each day’s findings. There was so much I wanted to know, like, “where did you learn to read and write? Did you like poetry? What was the final straw that made you leave everything you know? Or was it a slow burn that ignited your need to emigrate?”

Canada had jobs and Ontario had a mighty ship canal to build! The Welland Canal connects Lake Ontario and Lake Erie and is a major part of the St. Lawrence Seaway. The plentiful construction jobs on the Canal attracted different immigrants, and many were Italians.

What these immigrants were soon to find out, was that the most dangerous jobs were left to them. From 1913 to 1935, construction on the fourth Welland Canal took place and engaged 4,000 workers. 137 men lost their lives and several more laborers were involved in tragic, life altering accidents.

Immigrant jobs included placing explosives, mining, digging in dangerous areas, or precarious load hauling. If a worker went down, there was always another ready to take his place. There was a “flagrant disregard in Canada for immigrant life at that time....the Globe and Mail report: “The foreigners are known on the works only by a number, (so) it is impossible to ascertain their names.” “That was the way it was: so many were either unknown or allocated numbers.” When they died many were lost forever.”

Breda, Paola and Topan, Marino . Land of Triumph and Tragedy: Voices of the Italian Fallen Workers. Published by Verita. p. 468, 2019

My grandfather worked on the Welland Canal where he lost his left arm. He did many jobs but he was called a “loody man.” A “lood” is an old-fashioned Dutch word for a “plumb line” and is used to determine verticality. A nautical lood is used for determining depth. In order to clear a bridge through a lock, the nautical lood was dropped from the highest point on a ship to clear vertical height depending on channel depths in the Canal.

Reviewing documents and the postcard photo, I think he lost his arm between 1923 and 1924. The 1921 Canada Census has him working on the canal. He became a naturalized Citizen in 1923. I have since learned that to get citizenship, you had to be able-bodied. A 1924 photo postcard shows him with a prosthetic left hand.

Dear Papaco, As I was drifting to sleep, I saw you the day of the accident. Men running, shouting as they carry you away on a canvas stretcher. Conscious, in shock, in between worlds you barely track the chaos around you. So begins your life as a one-armed man.

The Prosthetic Left Hand and More Surprises

You passed away when I was eight, but I vividly remember you and Mamaco in the garden, and see you wearing your fedora and suit jacket with the left sleeve pinned up. I thought it was normal for men to dress like that when working in a garden.

In the photo with your prosthetic left hand showing, it looks nicely crafted. I soon discovered that Canada was pretty advanced with prosthetics by then.

“Canada and the First World War: The Cost of Canada’s War.” Canadian War Museum. www.warmuseum.ca/firstworldwar/history/after-the-war/legacy/the-cost-of-canadas-war/

In WW1, 3461 Canadians came home with amputated limbs. By 1918, the Amputation Club of British Columbia formed. Soon, other war amputee groups appeared all over Canada and merged together to become the War Amps to assist veterans with artificial limbs, recovery and adjustment.

Worldwide, countries focused “ to repair, repatriate and re-employ their disabled veterans.” This meant artificial limb development was in high gear.

“Building Bionic Men; Replacing Limbs Lost in WW1.” Adam Matthew: A Sage Publishing Company. May 5, 2017 www.amdigital.co.uk/about/blog/item/bionic-men

Before WW1, artificial limbs were designed to be functional without regard to weight or appearance. After WW1, surgeons and engineers focused on making lightweight, natural appearing prosthetic hands.

Where did Canal workers go to get artificial limbs? Based on archived newspaper articles, injured workers were taken to St. Catharines General and Marine Hospital, which was later torn down. How and where Canal workers got artificial limbs is still a mystery. With any genealogy search, sometimes a trail dead ends, for now.

Life In Canada

In October 1923 the Benincasa’s received their Canadian Citizenship papers. They bought a brick, 2 story house where they raised their family and rented rooms to other Italians. It was located across the street from the Old Welland Canal.

They were parishioners at Holy Rosary Church and the Thorold Italian community was tight knit. He was a member of the Thorold Legion Branch 17, which evolved from the Great War Veterans Association of 1915 and welcomed veterans from other countries. My cousin Helen recalls Papaco with his pocket watch, fedora and suit jacket taking her on frequent walks downtown and how he enjoyed visiting friends. He was a pleasant, quiet man who enjoyed smoking his pipe and listening to news on the radio.

The Story of the Charred Book and Hidden Darkness

Rapid fire knocks against the door- like loud cracks of gunfire. He quickly scans the room, grabs the book and wedges it underneath his arm to open the wood burning stove. Without hesitation, he throws the book into the flames.

Uniformed men enter without asking, or warrant, search his house and leave without explanation. He runs to the stove and pulls out the book of Italian poems with smoldering pages. The one-armed man gives a sigh of relief, reassured that his book is safe, and for now, so is he.

This wasn't Italy with Mussolini’s Black Shirts, it was Thorold, Ontario. My grandfather, a Naturalized Canadian Citizen was swept in to a little known, dark moment in Canadian History.

On June 10, 1940 Mussolini joined Germany and entered WW2. “ Within minutes of this announcement, the Canadian government gave the Royal Canadian Mounted Police(RCMP) orders to arrest Italian Canadians considered a threat to the nation's security.”

“Life in Canada: late 19th Century to World War II.” ITALIAN CANADIANS AS ENEMY ALIENS: MEMORIES OF WORLD WAR II. www.italiancanadianww2.ca/theme/detail/life_in_canada_late_19th_century_to_world_war_ii

The Canadian government designated Italian nationals—and Italian Canadians naturalized after 1922—as enemy aliens.” With habeas corpus suspended under the War Measures Act, 31,000 Italian Canadians were fingerprinted, photographed and ordered to report monthly to local authorities.

“Of these, over 600 were taken from their homes. Viewed as fascist supporters, and even spies, they were held in remote camps.” None of these people were ever formally charged in a court of law.”

“Life in Canada: late 19th Century to World War II.” ITALIAN CANADIANS AS ENEMY ALIENS: MEMORIES OF WORLD WAR II. www.italiancanadianww2.ca/theme/detail/life_in_canada_late_19th_century_to_world_war_ii

Between 1940 and 1943, Italian Canadians lived under strain of suspicion from neighbors and authorities. “There was the unofficial impact on the entire community: the sting of prejudice, businesses boycotted, jobs lost.”

Lederman, Marsha. “Shining light on a dark secret: The internment of Italian-Canadians.” The Globe and Mail. March 5, 2012 www.theglobeandmail.com/arts/shining-light-on-a-dark-secret-the-internment-of-italian-canadians/article551227/

They were fearful of having anything in their homes that would show their ties to Italy, even a book of love poems owned by a one-armed man, was too dangerous to have.

Fast forward. In 1988 The War Measures Act was replaced by the Emergencies Act that protects the rights of all Canadian citizens and permanent residents. It states that people affected by government actions during emergencies are to be compensated. More importantly, It notes that government actions are subject to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the Canadian Bill of Rights.

In 1990, at the meeting of the National Congress of Italian Canadians in Toronto, former prime minister Brian Mulroney apologized for the war internment "On behalf of the government and the people of Canada, I offer a full and unqualified apology for the wrongs done to our fellow Canadians of Italian origin during World War 2.

Oil Paint Insights And Final Journal Entry

Dear Papaco,

When I started my genealogy search, I thought that documents, records, passenger lists and photos would tell me everything I needed to know about you. But they only tell the where and when of your here and there.

When Helen shared her cherished recollections of you, little bits of personality would glisten. Like the time she sent me the letter you wrote to her mother with a recipe for Tordilli. (Ball-shaped deep fried rich flaky dough cooked to a dark golden color and dipped in honey served at Christmas)

Your handwriting is clear, beautiful. Each letter has its own identity. I don't know why, but seeing it endeared you even more to me.

I started to clean it up in Photoshop, meaning getting rid of stains, wrinkles so I can see your handwriting in and of itself. By doing this, I got a glimpse of you hiding in the letters. By freeing the letters they conspired to show me something of you that I did not know. This was a turning point, you became real and I now needed to paint your portrait so I could write the following:

I am the daughter of immigrants and I did this painting to honor my grandfather, who like so many in the Italian Diaspora of the early 20th century sought a better life in a new country. In this way he is no different than the many before him and after him, who fled desperate conditions of their homelands. In painting him, I honor them.

There go I but for the grace of one decision.

***

“Giuseppe Benincasa,” 2020, by Pat Benincasa, Pages from “Postuma,” book of poetry, wood, pocket watch + chain, framed military image, nautical lood, polyurethane, paint, 19” x 21.75” x 1.75”

“Giuseppe Benincasa,” 2020, by Pat Benincasa, Pages from “Postuma,” book of poetry, wood, pocket watch + chain, framed military image, nautical lood, polyurethane, paint, 19” x 21.75” x 1.75”

***

Join an intimate circle with Pat in conversation with genealogy researcher, Natalie Zett next week: Family Stories, Timeless Connections. More details and RSVP info here.

Additional portrait details and related photographs, along with bibliography available here. Pat Benincasa is a visual artist is a first-generation Italian-American and storytelling holds a compelling place in her DNA. Her work has received national and international recognition and her public projects include National Percent for Art and General Services Administration. She is the host of "Fill to Capacity," a new podcast series featuring conversations that veer off into the realm of life stories, insights, mistakes, joys and lessons learned and unlearned. Each episode ignites a spontaneous alchemy of shared experiences to reframe how we walk in uncertain times.

SHARE YOUR REFLECTION

2 Past Reflections

On May 16, 2021 Kristin Pedemonti wrote:

Thank you so much for this vividly detailed account of your grandfather; his struggles, his reality, his triumphs, his passions.

I too am doing my family's genealogy. So far the figure who stands out the most is my great-great grandfather Martin Quigney who fled Ireland from the famine 1852 and landed in Philadelphia Pennsylvania. In 2012 on a trip to Ireland for a guest lecture, I had the blessing to visit Tulla, County Clare and meet a distant cousin totally by chance in a small pub. To know more about where my own tenacity comes from & to know this one branch of the family tree heartened me to know more.

On May 16, 2021 Patrick Watters wrote:

Ah delightful. Some of us are fortunate enough to trace our ancestral origins, even the minute details. Exhaustive research and several journeys to places both somewhat near and very far bore fruit in my own quest. Irish, German Jew, and later too Lakota—ship manifests, Bibles and diaries, graveyards, and even a parish priest and Presbyterian manse helped me piece together my heritage which included much oppression and persecution, and even murder (genocide). My Grandmother, Pauline Job, was invaluable for both her own family, and also my Father’s Irish Lakota family, as she knew them well from all living in Nashua, Montana for decades. Yes, from Clan O’hUaruisce of Kingdom Dal Riada in the 5th century, to Tribe Job of Biblical history, it has been an enlightening journey with my ancestors. }:- a.m.

Mitákuye oyàsin, hozho naasha doo, beannacht and danke!

Post Your Reply