A Conversation with Meredith May: I Who Did Not Die

It was either Donna Billick or Diane Ullman, the founders of the Art and Science Fusion project at UC Davis who mentioned Meredith May to me. It was four years ago. We were probably standing out in their pollinators garden at UCD. “Just yesterday a reporter from the San Francisco Chronicle was up here. She keeps bees on the roof of the Chronicle building.” The image of bee hives on the roof of the Chronicle building in downtown SF captured me. I wanted to meet this reporter and asked for her name. It was Meredith May. As Meredith said, “The best interview I ever did came out of that!” And thanks to the connection, she sent me a note when her first book was published. It told a story very far removed from bees. This one was about the Iran Iraq War, one very particular, and quite extraordinary, story. Naturally, I wanted to learn more. Would she be up for another interview? It’s how Meredith and I found ourselves having our second long conversation. This one about her new book: I Who Did Not Die.

Richard Whittaker: You’re still at the Chronicle?

Meredith May: No. I left January 2015. I got an agent, and that prompted me to take the leap, and see if I could get a book written.

RW: Is this your second book?

MM: First. It’s not the first one I've written. It’s the first one that’s published. I had to put the other one I was doing aside, which is probably the one you’re thinking of. We talked about it earlier. It’s about my beekeeping childhood.

RW: Right.

MM: Yes. I was raised my grandparents, and my grandpa was a fourth-generation beekeeper in Big Sur. So, the story’s about being his sidekick and working on the hives in Big Sur, and delivering honey. It’s really about what the hive taught me about life and family, in the absence of having parents there to do it for me.

RW: What was the absence of your parents about?

MM: We lived in Rhode Island. They divorced when I was five. My dad stayed back in Rhode Island, and remarried and started a new family. So he was pretty distant. I visited him in summers for a couple of weeks, but that was it.

RW: You lived with your mother?

MM: Yes. And my mother, when the divorce happened, took me and my younger brother—I was four, and my brother was two—and she went back home to her parents. She moved back in with them and there were only two bedrooms. So she moved back into what was her childhood bedroom and we shared the bedroom with her. She fell into a depression and really didn’t get out of bed for a couple of years. When she did, she was just never restored as a parent.

RW: My gosh.

MM: She sort of regressed to being an older sister, and our grandparents took over. So she was there, but she wasn’t there, if you know what I mean.

RW: Thank heavens for your grandparents.

MM: Exactly. I think if my grandparents hadn’t been there and if I hadn’t found beekeeping, I could have turned out like a little hellion, possibly.

RW: Well, and people go through terrible childhoods. It’s just amazing how awful the circumstances are for so many people, and occasionally, maybe frequently, there can be an amazing resilience. But it seems like you need one person to kind of help you out.

MM: You just need one. I think what was hard for me was having my parent there, yet not participating. It’s confusing, because you spend your childhood trying to get them to participate. You just keep trying. I think that’s the hardest thing. It’s like being abandoned emotionally but not physically. It’s a really strange thing.

RW: That sounds hard to imagine, really.

MM: Yes, it’s very odd.

RW: I'm just putting together the new issue of works & conversations, and one of the artists who will be feaured grew up with a mother who was very depressed, who wouldn’t get out of bed, but he still had his father.

MM: Right.

RW: So what were the first stirrings of this new book I Who Did Not Die? How did you come to this story?

MM: I had a first draft manuscript of the memoir I wrote about my childhood and the bees. My agent sent it to a publisher, Regan Arts. They liked the writing, but they also happened to be looking for a ghostwriter to write the story of the two men at the center of this current book.

RW: I see.

MM: They wanted the book written in first person from both the men’s points of view. So the chapters would alternate in two different voices, which is a challenging and unusual structure for a book. But they wanted someone to write it for them. They looked me up, and saw a story I’d written at the Chronicle that got a little attention “Operation Lion Heart.” It was about a little boy in the First Gulf War who was injured when he picked up an explosive. He was flown to Oakland Children’s Hospital to recover. He lost a hand, an eye, and the lining of his stomach. He had to have his abdomen completely reconstructed.

RW: Oh, my God.

MM: I worked on it for a year. The photographer and I flew to the Middle East. It ran as a series over three days and won a Pulitzer for photography. It won a Pen Literary Journalism Award.

So the Regan Arts people looked me up and saw that, and they thought, “Well, we like her writing and she might know a little bit about the culture.” So they counter-offered with a different book, which—from what I hear—is not how book deals happen.

RW: So their counter offer was, you handle the story of this Iraqi and Iranian who were in the Iran-Iraqi war. That was the counter offer?

MM: Yes. They said, “Would you ghostwrite this instead of your own memoir?” I was disappointed, but then I did some Googling. There had been some coverage of this story in the Globe and Mail in Canada; they live in Vancouver now. When I read that, I thought, “Oh, my God, I’ve got to be a part of this!” It’s an amazing story. So I very willingly said, “Yes, I'll do it!”

RW: All right. So, how did that evolve?

MM: First the publisher said they wanted it in three months. I said, “Absolutely not. It’s not going to happen.” So,I negotiated and got six months, which was still ridiculous.

RW: Jeez.

MM: Yeah. But it was my first rodeo, and I wanted a book deal so badly. And after I said “Okay.” and signed the contract, I promptly freaked out! I didn’t know if I could do it.

I flew to Vancouver for a month and interviewed them separately. One speaks Farsi and one speak Arabic. So I had to find interpreters.

RW: And were they going to reimburse you for this? I mean, you had to pay for these people, I would imagine.

MM: Well, they gave me an advance to write the book, so I paid it out of that. So yes and no.

RW: I follow you.

MM: I wish my advance had been bigger, it would have been easier to afford. Interpreters are very expensive. They run about $50-$60 an hour. But I found two amazing interpreters. I flew up and just sat down with the men, around a table with a lot of food. One interpreter, the one who spoke Arabic, we met at his house and we would bring food and sit around the table.

RW: Now, which one was this?

MM: The Iraqi, Najah. So this would be the man who was saved by the child soldier.

RW: Is that his real name?

MM: Yes. I just found out it means, “successful test-taker.” So we would sit and talk for four to five hours at a stretch—with cigarette breaks and potty breaks and mental health breaks. It took about two weeks per man, that much talking.

RW: That would be like 14 days, you mean? Four hours, five hours a day?

MM: Yeah. four or five hours a day for five or six days. And before I started talking to them, I said, “You know, you’ve been interviewed by reporters, and they always ask you “What happened?” “Then what happened?” “Then what happened?” “How do you feel?” Right?

I said, “I’m going to ask you weird questions. I'm going to ask you what time of day was it? Did you smell anything in the air? What were you wearing? What kind of shoes? Was there mud on it? I’m going to ask you what you were thinking in that moment, over, and over and over.”

The way I explained it was, “This is like a movie, and I’m an actor. I have to pretend I'm you and write it on paper. So, I need to ask you very embarrassing questions.”

I wasn’t sure when I first met them, what they thought about women, just based on the culture.

RW: Right.

MM: But it turns out I had nothing to worry about. They were super open. Actually, neither of them are religious or have strict rules about anything, really. They were very, very accommodating, and both were very willing to tell their story. Najah owns his own delivery van. He moves people and has his own business. And he also sells stuff he picks up through his delivery business at the flea market. So his schedule was more flexible, and we usually met during the day.

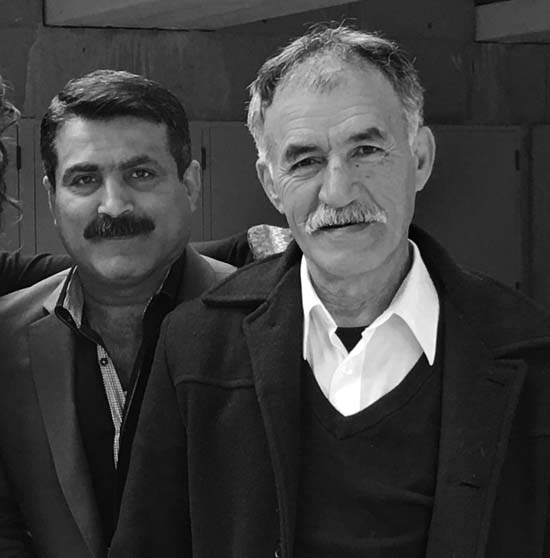

Zahed owns an auto shop almost an hour’s drive away from his house, and he works many, many hours. So I’d meet him at about five at his auto shop, and then we’d talk until 9:30 or 10:00 pm.

RW: So Zahed was the child soldier, right?

MM: Correct.

RW: And Najah was 26, 27, 28—somewhere like that, during the war. How old was the child soldier?

MM: Thirteen.

RW: Well when you learned about the story, you thought, “This is an incredible! I have to do it!” Looking back, can you say anything more about that intuition?

MM: It hit me. Literally, the hair on my arms stood up when I read about these men. There’s also a filmmaker in Toronto who had made a short documentary, and used actors to recreate the moment where the two meet on the battlefield, and the child soldier decides to have mercy, and nurse the enemy, nurse Najah, back to health. So I watched the film and I was in tears, because it’s the opposite of everything we hear. “We,” being Americans is what I mean.

Everything we hear about people from that area is that they’re violent, they’re terrorists, they’re crazy fanatics, they don’t like women, they’ll kill you in a heartbeat.

Actually, I never thought of this before, but what Zahed chose to do in not killing this stranger is the fundamental core of Islam—peace. But it’s gotten lost somewhere along the way. You know? It’s actually a very beautiful religion.

That was the first thing that got me. The second thing that got me was the beyond-infinitesimal chances of them ever meeting again, and the fact that they did 20 years later. This was after both had been tortured in prison, after both had been shot at several times, after both having to flee and escape their countries.

The fact that they happened to sit down next to each other 20 years later, halfway across the world—that tells me there’s something out there looking out for us.

We have a lot of words for things we can’t explain. We call it “God,” or “Allah,” or “Mother Nature,” the “Universe,” or “karma,” or “dumb luck.” We have a lot of words for it because we don’t know what it is, but this made me a believer in whatever that is. That is really powerful and, as humans, if we could just remember that and stop chasing money and power, and stop chasing greed and luxury, false luxury, and start chasing kindness—that’s what this book says in a very dramatic, compelling story.

It also gives you some history and a kind of a grounding, an understanding, of what’s going on in Syria and Iraq today. It has all of that together. This was like a grand slam, in terms of a story. I don’t think I'll ever come across a story like this again.

RW: That encounter between the child soldier, Zahed and Najah, on the battlefield, where the kid would ordinarily kill him—that moment, when something spoke between these two people at war—that’s an incredible moment right there.

MM: Yep.

RW: But then, as you said, the incredible circumstance 20 years later. Those two aspects of this story touch me, too. I think they’ll touch everybody on a level where, as you said, we don’t have good language for it.

MM: Yes.

RW: It’s too bad that we don’t have good language for it, maybe.

MM: Why don’t we?

RW: Our words for that are worn out. They’re used up and don’t have any weight.

MM: And I bet Native Americans or Eskimos have 100 words for what we’re trying to say. Do you know what I mean?

RW: That’s very interesting. It reminds of me Godfrey Reggio and Koyaanisqatsi. I should send you my interview with him. He was not a filmmaker, but he decided to make a film. He said, “I want one word that’s worth 1,000 pictures.” You know, the reverse of a picture is worth a thousand words. And he knew a very respected Hopi elder, and the Hopi elder gave him this word, a Hopi word—Koyaanisqatsi.

MM: That’s the word, Koyaanisqatsi?

RW: Yes. And it became the name of his first film. Phillip Glass did the film score, it was his first film score.

MM: That’s enough of a reason right there, to look at it.

RW: Godfrey Reggio had no training in film, nothing. But he wanted a word that encapsulated something he saw. The English translation of koyaanisqatsi is roughly “life out of balance.” After that he made a film called Powakaatsi. It’s from another Hopi word. A powaca is a black magician. Reggio described the film as being about how our culture is under the siege of black magic. He describes black magic as seduction through false promises. That pretty well describes the whole realm of advertising.

MM: Yeah. Because let’s just face it. Life is hard, right? I'm speaking in generalities, but I would say 75% of the time life’s hard for everybody. Right? And that’s what marketing preys on—if you have this watch, you’ll be popular. If you drive this car, you’ll always get a parking space. It just preys on our willingness to take a pill to get out of our problems, to avoid just sitting with our problems.

RW: Yes. And this book is the story of something that’s real, something that’s deeply true.

MM: And there is not much written about this particular war. I went to the library, and only found five books. They were all written in the 80s, except there was one written last year by a policy expert in Paris, Pierre Razoux, who wrote the introduction.

It was one of the most brutal wars of the 20th Century. 700,000 people died. 80,000 of them were child soldiers like Zahed. And the way most of those children died was they were made to walk through mine fields unarmed to clear a path for the real soldiers.

RW: That’s pretty unthinkable.

MM: There’s a scene in the book when Zahed does that.

RW: So what was it like talking to Zahed? Can you talk about how that all went?

MM: Asking him to talk about the mine field, or everything?

RW: Anything, really, but for the sake of time maybe you could go to that encounter when he decides not to kill Najah.

MM: There’s actually a specific reason why he made that choice. So, one of the more well-known battles during this war was called the Battle of Khorramshahr. Khorramshahr is a town on the border. It’s Iranian. Shortly after the start of the war, the Iraqis crossed the border and took it. They burned down homes. They raped women. They just plundered and took it, and kind of set-up there using it as a headquarters. They used it to push north into Iran.

So the battle where Zahed and Najah met was when the Iranians took it back. The Iranians encircled it and cut off all the roads leading out. They pushed in and took the Iraqis by surprise. There’s even some footage I found on the Internet, of the Iraqis when they knew they’d lost the battle and fled into underground bunkers. There’s footage of them coming out of the bunkers holding their white T-shirts up in surrender. And this became a sentence in the book. One man was holding up a plate with the prophet Ali on it, to kind of say, “Hey, I'm with the Iranians!” Because the Iranians love the Prophet Ali. So it shows men being flushed out of these bunkers and pouring out like ants.

That’s all to say that when Zahed arrived a day later, his job was to go into the bunkers and shoot anyone who was still alive. He went into three bunkers and found a lot of bloated bodies, but not anyone alive. Then he went into another bunker, and Najah was moaning on the ground. There was five or six corpses nearby and Najah was trying to communicate. They don’t speak the same language, but Najah was saying in Arabic, “Please don’t kill me, I'm a Muslim just like you.” The only word Zahed could catch was “Muslim.”

Zahed told me he was thinking, “Why does this guy keep saying “Muslim, Muslim?”

Then Najah was reaching into his pocket, because all the soldiers on both sides, traditionally carried a pocket Quran. It’s supposed to protect them in battle. So he was reaching into his pocket to show Zahed, “Look, I have a Quran. I'm like you!” And Zahed thought he was reaching for a grenade, because they’d often sew grenades into their clothing somewhere, so that in a situation just like this, you would just blow yourself up and whoever was near you.

RW: Right.

MM: So Zahed lunged and pulled out the Quran and then it fell open. And there was a Polaroid picture of Najah’s fiancée and their newborn baby boy. And that’s a whole other story, because there’s this great love story that happens in the book.

And Zahed saw it. The woman was very, very beautiful—Alyaa was her name. The way Zahed describes her was as “a Raquel Welch times 10,000.” He said it in English.” Then he added, “Oh, no. Raquel Welch plus Sofia Loren times 10,000. That’s how beautiful she was!” He knew immediately she was this guy’s girl and that was their baby. And he thought, “I can’t kill a baby’s father, and I can’t widow this beautiful woman.” And he’d never killed anybody up to that point in the war, and he really didn’t want to; he was a medic; that was his job.

He took pity just looking at the photo and realized, “Wow, this guy is just a regular guy with a family, who by some bad luck—like the kind I had—fell into this war. I’m not going to kill him.”

So that was it. He put the picture back into the Quran and put it back into Najah’s pocket. Najah was still scared and still trying to save his own life. He took off his watch—a gold watch, (Zahed insisted it was a Rolex, Najah doesn’t remember)—and was trying to hand it to Zahed. Zahed gave it back to him and then just made a motion with his finger by his lips like “shhh” and that’s when Najah knew he was safe.

RW: In meeting Zahed and talking with him what are some of the most memorable things that stand out for you? I’d like to hear about your experiences, basically, with each of these men.

MM: What I was struck by, and this was for both of them, they got emotional, but the only times that they cried, they cried for other people. They never cried for themselves. I found that really interesting. Both of them lost the loves of their lives, and I think that was the hardest for them to talk about; they both cried.

I'll start with Najah. I let them both roll on a lot. I would ask a question that could launch them into a good story. I paid attention to how they answered it, because that told me a lot about their personality and what was meaningful to them.

When Najah and I began, I was asking him to tell me about his life before the war—what were you doing? I wanted to try to figure out how he got into it, and we spent almost two days talking about him running this falafel restaurant in Baghdad. And he was just beaming having these memories.

RW: He loved that.

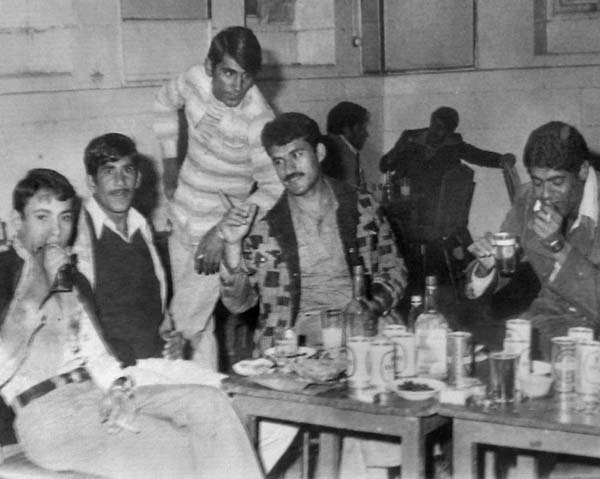

MM: I envision his place like the Cheers of Baghdad. Everybody went there and he’s like Ted Danson, the bartender. But the way he described it, he had a lot of customers and they would just hang out all night drinking tea and talking about Bruce Lee. It was called "Bruce Lee Restaurant,” and he decorated it with posters of Bruce Lee. And it was popular then. Men wanted to be him and women wanted to be with him. He was in his early to mid-20s. He showed me so many photos of that time in his life, and he had these John Travolta suits on, these tight polyester suits, and he was just making money hands over fist at this place.

Najah center, checked jacket

Najah center, checked jacket

He had a secret recipe for falafel that his sister and he developed. And this was going to be his future. He saw this restaurant as supporting his whole family. He has like five or six brothers and sisters. He felt powerful. He felt smart. He’s really entrepreneurial, and he was popular as hell, a great storyteller; he was just in his element. So that’s just one example of watching their excitement level when they talked.

RW: Right.

MM: I was worried that I knew a little bit more about the child soldier, Zahed, because he’d written his own memoir, and it had been translated into English. I’d looked at that, so I knew a lot more about him. What I knew of Najah was only after Zahed saved him and got him to a field hospital. They only spent three days together. After Najah was released from the hospital, he went straight to a prisoner of war camp, and he was a prisoner for 17 years.

RW: Oh, my God.

MM: So what I was concerned with was I didn’t know much of Najah’s story and I worried how would his story hold up to the other guy’s story. Because what am I going to say? Chapter 5, still in prison. Chapter 7, still in prison. Chapter 9, still in prison. You know?

But it turns out, first of all, he was sent to five different prisons, and they were all various levels of hell. They all had their own sadistic cultures. But the way Najah survived, because he’s entrepreneurial and because he’s smart and because he’s so charismatic, is he learned Farsi and he became the prison translator between the guards and the Iraqi prisoners.

Then he also became like the prison-yard storyteller. People would gather around every day, and he would tell all five Bruce Lee movies. But he would take a month to tell each movie and he did them in episodes, like a soap. People would come for the next installment. He would add more characters and twist the plot and then, when he ran out of those, he would start making up his own movies in his head.

RW: Did Scheherazade and One Thousand and One Nights ever come up?

MM: No, that one didn’t come up. But he was such a great storyteller when I interviewed him. He was gripping. I would be on the edge of my chair, because he’s the one who had a super-hot secret love affair with this woman—and in his culture, you do not talk to, much less sleep with a woman who you have not been granted her hand in marriage by her father.

RW: This is pretty scary stuff. Right?

MM: Super. He could have been killed. Well, more likely she would have been killed for it. But him, as well. So there is all this sneaking around at four in the morning, and outside the bakery. And that’s the picture of the woman and the baby.

RW: Okay.

MM: So when Najah went to war, he told her, “I'll just be gone for a couple of months, and then I'll come back and marry you.” And then it was lasting so long, he started panicking that she had been killed, like they’d been found out.

So, this book became a war story, a love story, a prisoner story, a refugee story, an immigrant story, a survivor story, a spiritual story. It just kept like opening like this flower.

RW: This must have been an amazing experience for you.

MM: It was. It was fascinating. I loved it.

RW: Now, you mentioned that the two were only together for three days.

MM: Yes.

RW: But that must have been pretty intense. What was happening there? I mean, how Zahed, the child soldier, “nurse Najah back to health”? That sounds kind of incongruous to me.

MM: Yes. But because he was a medic, he had access to supplies. So he would go to the medical tent and get bags of blood and morphine, and bring them back.

RW: As a kid, a 13-year-old, he knew how to do blood transfusions?

MM: Yes. He was already working in a field hospital.

RW: He knew what he was doing.

MM: He did. He knew how to do tourniquets and all kinds of stuff. So he actually used the bayonet. He jammed it into the wall, and hung the IV from it, and gave Najah fluids.

RW: Wow.

MM: He gave him morphine. He brought him water; I don’t remember him talking about food of any kind. But then he bandaged him up. He had a head wound and an arm wound. Then after three days of this, the Iranian commanders gave an order that any wounded enemies—they’d been killing a lot of them, but they said, “No more killing. Take them to the hospital.” And from the hospital, they became prisoners of war.

RW: I see.

MM: They don’t know why that order came down, and nobody ever will. I'm just assuming that the two countries were gathering up prisoners and using them as bargaining chips to try to get what they wanted from the other. I think the strategy became, “All right. Let’s just stop killing them and start trying to get something for of them.”

RW: Okay. So, tell me a little about your experience of interviewing Zahed.

MM: Zahed was a little trickier to interview because he still is really emotionally wounded by everything that happened to him. Also, he was tortured much more sadistically than Najah.

RW: And I remember from the part I read, that his father was pretty brutal.

MM: Yes. That’s the other thing. Thanks for reminding me. That’s why he joined the war. He was running away from a sadistic father, a very violent father, a cruel father.

Najah has a very loving, supportive family. Zahed didn’t, and he ran from it thinking, “War will be an escape, but it will also be this fun John Wayne thing.” He and his neighbor buddy ran away together. Little kids get great ideas when they’re together. Right?

RW: Sure.

MM: And then, even though Zahed was only a prisoner of war for two-and-a-half years, as opposed to Najah’s 17, I think the Iraqis in general, were much more cruel, and psychologically torturous—at least in the experience of these two.

The trick with Zahed is that in just about every one of the stories he told, he was always the hero. He had lots of stories of death-defying feats, and punching the enemy down. There’s just a lot of testosterone and ego going on there. I was getting really frustrated because it can’t possibly be true, and I'm supposed to be writing a true memoir. I was getting frustrated with him, but I'm also very sympathetic. I didn’t want to show him my frustration, but I needed him to get a little more real. What helped is I talked to my wife, who is a police lieutenant in San Francisco, and she is in the Special Victims Unit. So she deals with child abuse and domestic violence, rape. She said, “Look. First of all, it’s hard to recall childhood memories. He’s trying to recall traumatic childhood memory, and he’s probably still suffering from PTSD. So, the way he soothes himself is he remembers things and casts himself as the super hero.”

RW: Okay.

MM: So once I kind of understood that, I could direct my questioning a little differently. I’d let him tell me this fantabulous story, and then I’d come back with more specific questions. Like, “Well, how did you get the gun? Tell me that part again.” Then, after the third or fourth time, he told me a story that was believable. He needed a lot more managing.

RW: I can imagine that would be a huge challenge to get through to a very painful, but true material.

MM: Yes.

RW: Do you feel you managed there?

MM: I did the best I could. I feel solid with it. And the other thing is I gave a copy to both of the men to read before it was published. But I don’t think they read it because I kept asking them, “I need you to read it. Make sure there are no mistakes.”

I know Najah was reading it painstakingly, using Google Translate sentence by sentence. His brother reads a little English and has been in Canada a lot longer, so he was helping him. But I think for Zahed, it was too traumatic to read it. He just didn’t make much of an effort.

I said, “Zahed, I really would like you to read it, because I need to make sure you are okay with how you sound, and I didn’t say anything untrue.”

He said, “You know, I trust you 1,000 percent, and I will even be happy with your mistakes!” So, for what it’s worth, I feel it’s true. You know?

RW: That’s very touching, what he said.

MM: Yes. And the other thing I did was I read anything I could on that particular battle. The New York Times covered it, so I pulled all that. The U.S. military did a report on that whole battle. I found the operator’s manual for the Russian tank that Najah drove, and I read it.

So I tried to supplement everything they were telling me with anything I could read. Like Zahed went to Halabja, this is where Saddam gassed the civilian Kurds in his own country at the end of the war. Zahed was sent there a day after it happened to help dig mass graves.

RW: Oh, my God.

MM: So, I read a book on Halabja. I researched that and then I would say to Zahed, “So, were you carrying atropine?”

That’s the antidote the soldiers had to have in case they got exposed to the gas. Then I’d go on Google Images, which was so helpful, to find what I thought he’s talking about. And I’d show him a picture. He’d say, “That’s the one.”

Because you can go on Google Image, and you can —well, I'll just pick an example. Najah was trying to tell me about a bread called samoon bread. What’s that? I’d type it in, and then here are a hundred pictures of bread, all different shapes. He points to the one shape like a diamond and, “That’s it!”

So I would capture that image and put it in a file on my computer, and keep going. I transcribed during the interviews as well as recorded them, but also, I kept a picture file that I developed from whenever we came across things I wasn’t sure about.

RW: How cool.

MM: And Najah had bought a motorcycle called an MC-something. So I Googled it and he’s like, “Yeah, that one; green.” Google Images was really helpful. We even used Google Earth and found a picture of Zahed’s house.

RW: That’s amazing.

MM: Here’s another example. You remember in the beginning of the book, I wrote that Zahed tried to kill his dad with scorpion tea.

RW: Yeah, I read that.

MM: I'm like, “Come on. That sounds a little fantastical.” Well, sure enough, I did some research online,and found a report on scorpionism in Masjed Soleyman. It had this statistical research about how many bites per year and how does that compare to other Middle Eastern countries? What do the hospitals keep on hand for patients who come in with bites? What kind of bites? What kind of scorpions? It turns out this one little town in Iran is in the top 5 places in the world for scorpions.

RW: My gosh, that’s amazing.

MM: So, then I'll write that scene, because I have a little bit of background,” but I thought it was kind of BS at first.

RW: It’s quite a scene. It’s one of the chapters I did read, and the little exchange between the kid, who was— I forget the details.

MM: The neighbor kid?

RW: Right. The neighbor kid who was “too scrawny.” But the kid knew stuff the other kids didn’t know. He told Zahed how to do the scorpion tea. It was an amazing passage, and had the ring of truth about it.

MM: Thank you.

RW: It’s a fantastic story, but the way it turned milky white, and all those details were kind of compelling.

MM: Yes. Because when I'm interviewing them—we’ll use that, for example. I would stop Zahed every time, if I couldn’t see what he was describing. He said, “Put the tails in the tea,” and I'm thinking, “What do those scorpion tails do when you put them in boiling water? I'm sure it’s something gross.” And I wanted to know. So I asked him to tell me. Part of it was to offset my terror about the book not sounding believable. And I wanted to make the descriptions cinematic.

RW: Well, I only read a little bit, but it was pretty compelling. The brutality of his father is pretty awful, and one realizes there’s a lot of kids that suffer from violent, brutal fathers, and not just in Iraq.

MM: That part of Zahed’s story had not been told in the media, why he joined the military as a kid, and I knew that the book had to start there. You had to understand why a 13-year-old would voluntarily leave home to join the front lines? There had to be a compelling explanation for that.

RW: Having made this dive through the stories of these two Middle Eastern men, talk about how that affected your vision of this whole Middle Eastern reality.

MM: God. Well, it’s made my heart so raw that I can barely look at it. When they had that picture of the little boy from Aleppo who was dazed and dusty, like the image of him went viral; he was in the back of an ambulance. It was probably two or three months ago. I still see that in my head.

It’s made me think that we never learn from history. We’re just doing exactly what we’ve been doing since—well actually, going back to the Ottoman Turkish empires. That area is caught in the grip of two worldviews living side-by-side that completely disagree. And adding to the complexity, on top of a very rich resource—oil.

This article is syndicated from works & conversations, a collection of in-depth interviews with artists from all walks of life. Author Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

On Oct 13, 2017 Kristin Pedemonti wrote:

Thank you Meredith May for your heart in both saying YES to capturing this story of such deep humanity. I was in Khorramshahr Feb 2015, the first American Storyteller accepted into the Kanoon International Storytelling Festival. I heard stories of the battle. I am so grateful for people like Zahed who can see the other human in front of them and remember their heart. So happy to hear that Najah and Zahed re-met so many years later and in Vancouver. I can only imagine how healing that was for both. <3

Post Your Reply