God Who Weeps: A Story of Grief and Redemption

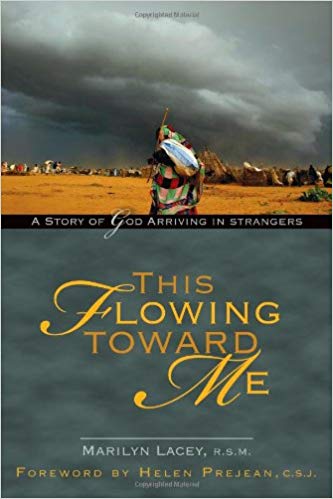

The following is excerpted from This Flowing Toward Me: A Story of  God Arriving in Strangers", by Marilyn Lacey, R.S.M, published by Ave Maria Press, 2009

God Arriving in Strangers", by Marilyn Lacey, R.S.M, published by Ave Maria Press, 2009

Sr. Marilyn Lacey is the founder and executive director of Mercy Beyond Borders, a non-profit organization that partners with displaced women and children overseas to alleviate their poverty. The organization brings hope to more than 1,400 woman and girls annually by providing educational, economic and empowerment opportunities where there are few options to escape extreme poverty. A California native, Lacey has been a Sister of Mercy since 1966.

G.K. Chesterton tells the story of a person--let's call him Joe--who lived a rather unreflective life and was entirely indifferent to spiritual matters. Early in mid-life, Joe unexpectedly died and slid unceremoniously into hell. Joe's old buddies really missed him. One evening, over a few beers, they formulated a plan to rescue him. They decided that Joe's business partner should go down to the gates of Hell to negotiate springing him from the place. He knocked and knocked, pleaded and pleaded, but the gates never budged; the heavy iron bars stayed firmly shut.

Next his parish priest went down and requested an appointment with Satan himself. He carefully laid out the case, "Look, Joe wasn't really a terrible fellow. Given more time, it's possible that he might have matured. Let him out, please!" But Satan was unmoved, and the gates remained closed. The men did not know what else to do.

Finally Joe's own dear mother went and stood outside the terrible gates. She did not bang or beseech or beg. Amazingly, she did not even ask for her son's release. Quietly and with determined voice, she simply said to Satan: "Let me in." Immediately the great doors swung open to admit her. "For love," Chesterton wrote, “goes down through the gates of hell, and there redeems the dead.”

Chesterton’s parable would not have made much sense to me had I not walked with refugees these past twenty-five years. I started out not like Joe’s mother, but rather, much more like Joe’s buddies, thinking I could rescue the refugees from their hellish situations in the camps. I am now convinced that wisdom lies in simply being with them wherever they are. I came to this understanding rather slowly, and not without difficulty.

The six weeks that Nhia Bee’s family spent at our mother house opened my eyes to a larger world, one that I was now eager to explore. And so I made arrangements through the friend of a friend to set off for Thailand for a year’s immersion in a refugee camp.

When I first set out, I might as well have been Indiana Jones. Each day was sheer adventure. I’d never been out of the United States before, and now here I was flying off on my own to Bangkok. As I said earlier, my initial calling to this ministry had been through a dream in which it was quite clear that the refugees would be teaching me many things, above all “a new way of loving,” but I’m afraid I lost sight of that humble perspective shortly after the wheels of the nearly empty 747 lifted off from the runway at the San Francisco Airport.

Besides the crew, the charter plane carried only ten passengers, all headed for work in refugee camps. The plane was heading to Thailand in order to pick up a full load of Southeast Asian refugees destined for permanent resettlement in the United States. In the company of nine seasoned refugee workers, I managed to transform myself, within the space of a twenty-two hour flight, into a grand emissary of mercy, an agent of God who would do great things, able to leap tall oceans in a single bound, sent to rescue beleaguered exiles.

I was overjoyed to be on my way. Never mind that I didn’t care for rice (or camping, for that matter), spoke no foreign language, knew next to nothing about the refugee camps, had only a six-week visa (though I planned to stay a year), and had absolutely no idea where I would be working. In my pocket I carried the address of a convent in Bangkok, along with a written promise from one of the Sisters there that yes, certainly, she could find some way for me to work in a refugee camp somewhere in Thailand. Talk about unprepared! Yet I was incredibly happy and calm, confident that everything would fall into place. I slept peacefully for ten of those twenty-two hours and arrived in Bangkok alert and refreshed.

The year was 1981. The US hostages in Iran had just been freed. Ronald Reagan’s elevation to the Oval Office, like a Hollywood script, was playing out before crowds who wanted to forget about domestic inflation, defeat in Vietnam, and humiliation in Tehran. Americans were yearning for old-fashioned, feel-good, flag-waving patriotism. But all was not well in the world. Partly as a humanitarian response to the televised anguish of the “boat people,” partly to assuage our own national conscience about the war that had ended so badly—but mostly to address the political sensitivities of the United States’ remaining allies in Southeast Asia—Congress had decided to allow tens of thousands of refugees into the United States from camps throughout the region, I, as a refugee camp worker, would be one small player in this brave new exodus.

Bangkok’s Don Muang airport was, in those days, surrounded by rice paddies and patches of thick green vegetation spliced by dirt roads and transportation klongs (canals). Palm trees lined the runway. I stepped down from the plane onto a liquid-looking tarmac that shimmered with equatorial heat and walked into the terminal, where slow- moving, smiling immigration officers and customs inspectors greeted me and waved me through. So far, so good. One of my fellow passengers kindly offered me a lift into Bangkok in the van of her relief organization.

On that initial eighteen-mile ride into Bangkok, I nearly overdosed on the dizzying meld of unfamiliar sights, sounds and smells. We sped along on a fairly modern freeway, just inches away from women in sarongs and straw hats who were bent double, sweeping the roadside with short-handled brooms. We passed thatched houses on stilts above the narrow brown klongs. Closer to the city we saw huge construction projects underway, with barefoot men and women clambering up and down rickety high scaffolds made from bamboo lashed together with vines of some sort.

As we neared Bangkok, the traffic slowed and thickened and then clogged: cars, vans, and buses belching black fumes; open-air three- wheeled samlors (taxis), motorcyclists, and bicycle riders dodging in and out; not to mention the occasional elephant plodding along, prodded by a mahout astride its thick neck. Traffic moved on the left, British style, but without lanes or discernible traffic regulations. Swirls of chaotic movement vied for the same space, accompanied by the honking of horns and the dashing of pedestrians across the streets wherever the noisy churning clotted enough to allow it.

There was literally too much for my Western eyes to see. Sidewalks were crammed with vendors walking along with heavy baskets slung from poles over their shoulders. Fruit stands, beggars, shops, and shrines. Incense from the street-side altars mixing strangely with the sizzling smell of who-knows-what from hidden kitchens. Buddhist monks in yellow robes walking beside men in finely-tailored business suits. Pictures of Levi’s jeans and Fanta cola on giant billboards loomed over families who squatted on the sidewalks, cooking their breakfasts on tiny charcoal fires. My brain was on sensory overload by the time the van dropped me off at my destination, a walled convent compound on Bangkok’s Ploenchit road.

The community of Sisters there--native Thai nuns as well as missionaries from France, the Netherlands, and the United States—were exceedingly gracious to me. My guest room had open latticework on two sides, and when the monsoon rains came that first night, I realized why. The hot winds could blow freely through the room without knocking the walls down. This fascinated me, as did the lightning and tremendous thunderclaps. The next morning I learned that several tiles from the spot directly over my bed had been dislodged by a lightning bolt that struck the roof. That just added to my general excitement. I felt close to the Earth, close to the life pulsing through the place.

I spent one week in Bangkok acclimating to the weather and food and making arrangements with the Catholic Office for Emergency Relief and Refugees for my assignment. Then I rode twelve hours north-by-northeast on a train to the village of Nong Khai, the location of the refugee camp where I began teaching English.

During the ensuing months, as I worked side-by-side with the La refugees who lived within the barbed-wire enclosure of that dusty forgotten corner of the Earth, those images of myself as Super-nun wilted completely.

The Vietnam War had ended six years earlier, but its proxy war in neighboring Laos was still simmering. Organized resistance to the Communist government by the Hmong and other groups inside Laos collapsed in 1975 with the withdrawal of American funding and advisers, and many thousands of Lao people were arrested and held in “seminars,” a euphemism for forced labor camps. They were imprisoned and “reeducated,” as one Lao refugee explained it to me, “until our thinking would be right.” When these internees escaped or were released, some joined secret guerilla resistance groups; thousand of others looked for ways to escape from the country. They became refugees.

These refugees, I soon learned, were held in local jails after they had crossed the Mekong River and landed on the Thai side of the border. After being interrogated, they were processed into the camp. Their living quarters were eighteen inches of space per person on six-foot deep bamboo shelves in long, thatched barracks, with a flimsy fabric curtain hung to separate the compartments. A family of four, for example, lived on a platform six feet square. It was raised a few inches above the dirt ground to provide some protection from scorpion and snakes, of which there were plenty. Water was strictly rationed.

A family of seven received three gallons in the morning, and three more in the evening. This had to suffice for cooking, drinking, bathing, and cleaning. Thai guards controlled the camp, and refugees needed special permits to go out even briefly. The United Nations had an office inside the camp, but their workers were largely powerless to enforce any standards except those sanctioned by the Thai government. A few non-governmental organizations were allowed to function inside the camp, running the camp hospital (a makeshift clinic in a narrow wooden barrack) and helping out in the schools.

I settled into a routine, month after month, of hypnotic sameness. The heat, the dust, the pervasive poverty, the unchanging pattern of the refugees’ confined, artificial existence, all forged a strange sense of near-normalcy to the situation. Occasionally, however, I witnessed things that shook me deeply. A three-year-old girl singing to herself while she played with her newfound toy: a dead rat on a string. Newlyweds who had nothing to serve to their wedding guests but watermelon seeds (until the local Sisters saved the day with a bottle of whiskey). The drowning death of a refugee child in one of the camp ponds: “We couldn’t have prevented it,” the grieving parents explained. “That pond is haunted.”

My adult students were, compared to most of the American teens I had taught, positively zealous in their pursuit of learning. In the Lao culture, teachers are revered; accordingly, the refugees treated me like near-royalty. They were accustomed only to rote learning. Teacher says a sentence; students repeat it in unison. I, however, taught American-style. We engaged in spontaneous conversations, we did role plays, we invented grammar games; we read short stories and then discussed them, In their eyes, I was the world’s most creative teacher. They greeted my simplest lesson plans with rapt attention. No one was ever absent. One morning Sourasith came to class shivering, sweating, and flushed. I asked if he was sick. “Oh yes, I have malaria; but I didn’t want to miss class!”

Over time | learned their stories. A twenty-five-year-old named Viengthong told of spending many years in “seminar.” He described being locked into a room with seventy other men. For two years and eight months, he was never allowed out of that room. He never had a bath. He never had a change of clothing. Thirty-seven of his companions died. The room had one small window. When it rained, everyone crowded near it to catch some of the water trickling in so that they could wash. At one point several prisoners who had been Viengthong’s friends escaped. As punishment, the guards bound Viengthong’s legs to a wooden board for six months, leaving him unable to move.

When he was finally released, his legs remained useless for another two months. He dreamed only of crossing the Mekong to freedom. As soon as he was strong enough to walk and swim, he escaped to Thailand. Three of his brothers and sisters had fled earlier, but he had no idea where they were—elsewhere in Thailand? in America? France? Australia? Now he was alone in Nong Khai, confined to a refugee camp ringed by guard towers and barbed wire, but happy to be alive.

There was great excitement in Nong Khai the morning that a baby elephant swam across the Mekong from the Lao side to the Thai side. Villagers quickly corralled it. The joke then circulated that, when the police interviewed it, the elephant claimed to have escaped because it didn’t want to live under a Communist government.

To many of the refugees, it wasn’t a joke. Some in the camp were members of the Lao Freedom Fighters, a collection of resistance groups that operated nineteen semi-secret guerilla encampments along the border. Each group answered to a different leader. The groups worked independently, but all had the same goal of harassing and ambushing military troops inside Laos. Kham Oui, one of my adult students, often bragged of the Freedom Fighters’ exploits, At his repeated urging, I agreed one day to visit some of the guerrilla sites. The trip was hastily and quietly arranged, as these encampments were off-limits to foreigners.

Kham Oui and I climbed into a battered pickup truck, which then sped along the road that roughly parallels the Mekong. Every hour or so, the truck veered off the road and stopped beneath a tangle of trees.

The driver jumped out and motioned for us to follow him into the for- est. Soon a young soldier would meet us and take us into the camp. An honor guard of sorts—a ragtag lineup of twenty men and three women—had been assembled to greet us at the first camp. They offered us flowers. They stood at attention in the heat, not moving (even though biting red ants swarmed over their sandaled feet) while the officer-in-charge gave a welcoming speech. I then spoke, using Kham Oui as my interpreter, with two teenagers who said they’d been fighting for five years. “Yes, I’ve killed many enemy soldiers,” said one in response to my question.

In another such camp there were groups of young men whose black hair hung far below their shoulders. They had vowed never to cut it, they told me, until Laos was once again a free country. The next camp, called Hui Suam, was ringed by bunkers fortified with sandbags. About fifty soldiers lounged about, but their uniforms were tattered, and their thatched huts in disrepair. One hundred of their compatriots, | was told, were across the river, fighting inside Laos. The leader disclosed that he had recently lost sixty men in fierce fighting. Of course, it was impossible to verify their stories, though it was clear that these people had made a serious commitment to the resistance effort.

At Ban Pheng, another camp, I met a twelve-year-old boy guarding the place with a rifle. I saw other children sick with “forest fever” (malaria). ! talked with a woman who commanded a fighting force of thirty women. Now and then during my year in Nong Khai, I read re- ports in the Bangkok Post of military skirmishes on the Lao side of the river. One such article corroborated the verbal description given by one of the refugees that his guerrilla unit had blown up an ammunition depot inside Laos. The sad fact, however, was that these soldiers were impossibly outnumbered and ill-equipped to tackle the Vietnamese who occupied their homeland. For the Lao Freedom Fighters, it would be a long, terribly costly, and ultimately fruitless struggle.

During my year in the camp | witnessed numerous examples of corruption. One was particularly galling, since it involved adults stealing from refugee children. The German Red Cross announced that it would be delivering forty large crates of school supplies to the elementary school in Nong Khai camp. The whole student body assembled at 9:00 in the morning in the open courtyard. Under a blistering sun they stood in formation for three hours until the representatives finally arrived. Then they stood through tedious official speeches. All the while the students eyed the piles of cartons in front of them. The German delegate then opened one box, ceremoniously handed pencils and notebooks to exactly three students while getting his picture taken, and drove off waving from his air-conditioned van. The refugee camp commander, a burly Thai man who never smiled, stepped up and barked an order to his aides as soon as the visitor had disappeared: “Put half the crates into my van.”

He dismissed the assembly and drove off in a cloud of dust to sell his stolen goods for personal profit. I was appalled, then indignant, then outraged. The Lao teachers, for their part, tried to calm me down. “Are you surprised? This happens all the time. We must be grateful for what we receive, not upset by what never reaches us.” They went on to explain, “Why do you think we are always hungry? It’s because two-thirds of the rice rations from the UN ‘disappears’ before distribution.” This was my introduction to the daily indignities endured by the refugee poor.

Their maddening passivity, however, only fueled my fury. That night I told the Sisters that I intended to write an expose of the incident for the local newspaper. Seriously alarmed, they begged me to reconsider. “At the very least, you will be expelled from the camp and your visa revoked. More likely, you will be killed. We would find your body floating in the Mekong. How would that help the refugees? Write the story if you wish,” they advised me, “but not until the year is over and you are back home in the States.”

Just before my year there ended, Nong Khai camp was shut down by the Thai government, and all its inhabitants bused a full day’s drive to an “austerity camp” at Nakhon Phanom, in a more barren sector of northeast Thailand. For the refugees, it must have seemed the very end of the earth. The reason for the move? Some policy-makers in Bangkok had decided that Nong Khai camp was too luxurious—that it might be attracting people out of Laos, especially since (after years of waiting) some of the Nong Khai refugees were now being considered for resettlement in France, Australia, or America. To erase any such incentive for further refugee inflows, the Thai government planned to raze Nong Khai camp. The new camp, Nakhon Phanom, would be closed: no outsiders permitted. Food and water would be rationed much more tightly. There would be few health or educational services inside. And most discouraging of all, the refugees would not be eligible to interview for the possibility of permanent resettlement in the West. The austerity-camp policy thus narrowed their future to a forced choice: either stay inside the refugee camp forever, or repatriate (that is, return voluntarily) to Laos. Watching those buses carry my refugee friends off to Nakhon Phanom was one of the bleakest hours of my life.

It made my coming home all the harder. The refugees I'd grown so close to were now in the austerity camp. They didn’t have enough to eat. They didn’t ever expect to be released or resettled elsewhere. They were cut off from the outside world. Meanwhile, I was back in the United States, where my friends were eager to celebrate my homecoming and take me out to dinner to hear all about my adventures. Sitting in a restaurant, facing a full plate of food, I would see only the refugees’ meager rations. I knew that the amount on my plate could feed an entire family, The food stuck in my throat. Hiking with friends in the California foothills, surrounded by the beauty of open fields and wildflowers, I would visualize the confinement of the refugees who had no freedom of movement, their days circumscribed by double rows of barbed wire fencing. My choice to spend ten dollars seeing a movie with a friend weighed on me; that money, if sent instead to the camp, could have purchased medicine for Somchai’s sick child.

A pervasive sadness settled over me. Sure, my friends enjoyed the stories about strange things | had eaten (I enjoyed recounting them), but very few really wanted to hear me talk about the refugees’ anguished lives. Perhaps they thought I exaggerated. Maybe they didn’t want to know about problems halfway around the world. Certainly the stories I told were out of place in suburban America, where the word camping conjures summer vacations, not misery upon misery.

Most of all, I was hopelessly inept in the telling. The pain I felt because of my involvement in the lives of the refugees lay heavy and unspoken within me, like a wounded animal. I had no clue how to communicate it. What good were words, anyway? My friends had not been where I’d been, had not seen what I’d seen. How could I expect them to feel what I was feeling? Was there any chance that this world could overlap with their world—my former world—in any comprehensible way? Could I straddle both, or did I need to choose?

At the time, I had never heard the words reverse culture shock. Not really knowing what I was going through, I pushed aside my sadness and plunged into working for a graduate degree in social work at UC Berkeley, the degree that would position me to do refugee resettlement work stateside. By day, I pretended to care about my studies. I participated in classes, buried myself in the library stacks, wrote papers. By night, however, I painstakingly deciphered the letters that were arriving regularly from the austerity camp. With the help of my English-Lao dictionary, the words slowly untangled themselves from their foreign script and tumbled into troubled coherence on my desk:

Please, Sister, in your prayer ask God to bless my family, to let me be successful in my hope for resettlement. If I fail this time, how can I endure further in this camp without any hope and no more chance? This makes me thoughtful and sad. I am afraid I will be sick some day.

—Khamphiou

Sister, last night I dreamed you came back to the camp in a helicopter and rescued my family and me. I woke up happy, but it was not true.

——Syda

Sister, my life is hard now in this austerity camp. But I dug a well for my neighbor, and I think that God will remember this one good thing I have done in my life.

—Niraphay

Their correspondence piled up on my desk, making my academic work seem less and less relevant. I did what I could, answering their letters, enclosing money orders whenever I received a donation from a friend, letting the refugees know that they had not been forgotten. All the while my own survivor’s guilt mounted. Of what possible use was a term paper when my friends were suffering? Why was I wasting time on this campus reading about the history of social work when I could be doing something practical to help the refugees?

I began reading the Gospels differently. The cure of the paralytic at the pool of Bethsaida (chapter 5 of John’s Gospel) rewrote itself into my prayer journal:

Now in Thailand by Nakorn Phanom there is a place with the name Napho Camp. Inside its barbed wire enclosure 22,000 refugees lay paralyzed, without freedom, barely surviving—waiting for the slightest movement in the web of international policies that bind them. There were many who had been held captive there with their families for years and years, Jesus, who knew they had been stuck there for a long time, said to them, “Do you want to be freed?” “Sir,” the refugees answered, “We do not have anyone to sponsor us even if the situation should change...’

My agitation increased. I stopped getting together with friends. 1 considered returning to Thailand to live inside the austerity camp with the refugees. Even today, I recognize that there is value simply in accompanying exiles, in choosing to remain with them. At the time the idea appealed to me strongly, but I knew that the Thai government now forbade the presence of foreigners inside the camp. Not even teachers or nurses were allowed in; I could never hope to gain access to live among the refugees now.

And what, precisely, could I do for them, anyway? What were my options? Being a nun with a vow of poverty, I had no personal income at my disposal. Maybe if I left the convent and got a good job somewhere, I could send the money to the austerity camp. This thought was quite seductive, appealing as it did to my none-too-subliminal savior complex: If God could not be roused to rescue the refugees, perhaps I could save them myself. Prayer was becoming difficult. When I did pray, it was more like sparring. For some time I gave it.up entirely. I was angry with God. There was no end to the suffering of the refugees. Didn’t God care? On my annual prayer retreat, I wrote an open letter to God, spilling forth my feelings:

Yahweh,

Do you see these tears? Have you read any of these letters from the austerity camp? Can you see Bounchanh and his wife and children? He writes that his heart is broken, but that he still finds some peace because he truly believes you will some day “help him to get out of this...” I cried—no, I broke down and sobbed—when I read those words. Then I felt like screaming, “No, it’s not true! God won’t rescue the poor man.”Oh, sure, I know that the Scriptures are full of such promises, but they seem empty now, all of them.

When has the poor man ever really been saved? (And I don’t mean after death; that hardly seems to count.) Shall I write to - Bounchanh and tell him that it’s all been a terrible lie? He is one of the few Christians in the camp, and he looks to me for support and encouragement in his faith. Well, he'd surely be scandalized if I shared what I’m really feeling right now: there is no way out for him. The poor will always lose. No one cares about—or even knows about—the austerity camp. America isn’t going to help the Lao people. You aren’t going to help them, either. And I am powerless to help them.

But the faces are still here, God. I see them one by one. I know them by name. They are my students, and I am still their teacher.

Their letters keep coming:

Sister, if you receive my letter, please answer and give some opinion that push my heart to be happy.

—Souksavanh

Sister, I was 20 years in the army, 6 years 2 months and 25 days as a prisoner of war in Laos, and now how long will I be in this refugee camp?

—Komsensee

Sister, don’t let me down about the sponsor. J and my family depend on you.

—Bounchanh

Teachers are revered by the Lao people. These refugees now look to me, their former teacher, and write to me with utter candor. They pin their hopes on me. But what can I do in response? Nothing! I’m not an ambassador; I don’t have political connections. I’m not good at crusading. I was born to lead a quiet life. You called me and led me to identify with the poor, and I gladly followed; but now look what's happened! All these refugees have turned to me—but I don’t even have an independent salary to share with them. Besides that, my friends tell me I’ve changed, and they no longer know how to connect with me. I feel unspeakably sad.

You know very well I’m angry with you, God. Restless. Unable to pray. Why don’t you break down the dividing wall that keeps us apart? I don’t feel any initiative from you, any outreach. All I feel is this awful lump of smoldering anger. And guilt, paralyzing guilt. How am I to enjoy the luxuries here--the ample food, the swimming pool, our carpeted and cushioned lifestyle? None of it is bad, but I can’t relax and “go with it" anymore. Being home is not working well for me.

Lately, I’ve tried admitting the pain of it, telling friends little by little. But where are you, God? Are You the comforter of the afflicted? Refuge of the poor? God-who-has-always-been-with- me? Or are you a God who sees but does nothing? God who allows sickness when there is no money for medicine. God who speaks of love but lets cruelty reign. God who extols gentleness only to watch it be crushed behind barbed wire. God who listens to the prayers of rich Christians all over the globe but does not change their hearts. God in whose name wars are waged. God who remains silent in the midst of suffering. God who sidesteps all these questions by pointing to the cross.

Which God are you? And why don’t you answer these tears? I have always wanted to love you.

God chose not to respond on my timeline. Nevertheless, the act of venting provided me some relief, and so I plowed back into academia with anger simmering on the back burner. God and I were now at a stand-off.

Then one day I experienced something like a waking dream. I was not praying, but merely sitting in a garden near the university, mulling over the mess in which I felt so mired. Without intending to, I suddenly found myself in dialog with the God whom I’d shunted aside for so many weeks.

Suppose you had a brother whom you loved, I said to God. Suppose your father lavished abundant gifts on you, but gave nothing to your brother. In fact, he locked him out in the backyard and ignored him, leaving only a small bow! of scraps for him to eat once each day. How long could you continue to enjoy all of your own comforts and privileges inside the house? How long could you abide “praying for your brother” from a distance? How long before you would begin to resent this father who supposedly loves all his children, especially the poor?

And if you spent some time outside in that empty yard with your brother and grew very close to him and felt his anguish at not being able to feed and clothe his own children, and saw that---despite the mistreatment—he still loved his father and asked imploringly, “What did I ever do to offend our father, that he should treat me this way?’

After all that, would you want to meet your father again face-to-face inside your comfortable house? Wouldn’t you be afraid that you would hate him?

And much to my surprise, God replied:

You know that’s not how it is, Marilyn, though I understand why you feel this way. I have many children. Some of them locked your brother out of the house. My heart is out there with him, but I’ve left people free. They do with me as they please. You see, love can’t force anything. I’m as powerless, really, as a quadriplegic. They surround me with linen and candles, with solemn processions and profusions of flowers, and they deluge me with their prayers. But oddly enough, only a few of them really take notice of their brothers and sisters. It breaks my heart, too.

I'm glad you've noticed them. Go ahead; be angry, but please don’t hate me. I am with you in this, more than you could ever realize. And I am with your brothers and sisters in the camps, too, even as I am blamed for the burdens they now bear. Come now, let your tears flow. See, I am weeping with you.

Our stand-off ended right then and there, as God and I wept together in that Berkeley garden. Since that moment, I have understood God differently. No matter what the theologians may say to the contrary, | know that God is not All-Powerful, at least not as most of us understand power. Why not? Because those who love never exert control over others. Because loving makes us utterly vulnerable, as C.S. Lewis described in his book The Four Loves:

To love at all is to become vulnerable. Love anything and your heart will certainly be wrung and possibly broken. If you want to make sure of keeping it intact, you must give your heart to no one, not even to an animal. Wrap it carefully round with hobbies and little luxuries; avoid all entanglements; lock it up safely in the casket or coffin of your selfishness, But in that casket--safe, dark, motionless, airless space, it will change. It will not be broken; it will become unbreakable, impenetrable, irredeemable. The alternative to tragedy, or at least to the risk of tragedy, is damnation. The only place outside Heaven where you can be perfectly safe from all the dangers and perturbations of love is Hell.

Chesterton was right. Love wants to be with the beloved. Love can’t fix things, but love always knocks and comes right in to be with the beloved in the midst of their suffering, even to the depths of hell. Love does not isolate or insulate; love chooses to be with. Love does not coerce; it can only invite. God waits: “Here I stand, knocking at the door. If anyone hears me calling and opens the door, | will enter the house and sup with her, and she with me” (Rev 3:20).

Despite our persistent and stubborn expectations to the contrary, God never promises to take away our pain, but rather pledges to remain close to us in the midst of it. The prophets invite us to “call his name Emmanuel, which means, God With Us” (Is 7:14). We have God’s word on it: “Behold, I am with you always, until the end of the age” (Mt 28:20).

On this pledge, everything depends.

The following is excerpted with permission, from This Flowing Toward Me: A Story of God Arriving in Strangers", by Marilyn Lacey, R.S.M, published by Ave Maria Press, 2009. Sr. Marilyn Lacey is the founder and executive director of Mercy Beyond Borders, a non-profit organization that partners with displaced women and children overseas to alleviate their poverty. The organization brings hope to more than 1,400 woman and girls annually by providing educational, economic and empowerment opportunities where there are few options to escape extreme poverty. A California native, Lacey has been a Sister of Mercy since 1966.

On Apr 24, 2019 Jack Forrest wrote:

Thank you for sharing such an empowering story, sister.

You mentioned the theft by camp supervisors. How much of donations reach the refugees and how much is stolen? How can you control this?

Post Your Reply